Perspectives

8 MIN READ

In this second part, Tim I Gurung details his last days as a British Gurkha and why he chose to leave the army life.

This is the second part of a series on Tim I Gurung’s life and experiences, first as a Gurkha soldier, then as a businessman and writer. The first part can be found here.

My unit happened to be in Brunei when we got our six-month-long unpaid leave to return home after serving for three years in the British Army. I was so excited to go home that I couldn’t even sleep the night before we boarded a plane to Kathmandu. Houses like piles of red bricks appeared underneath us as I looked excitedly out of the airplane window. My heart swelled with emotion. But by the time we had landed, cleared Nepal’s treacherous customs, and reached the British Gurkha Nepal Camp, it was already late and time for bed.

Early the next morning, we got into a chartered bus to Pokhara and headed home. After spending a night at a relative’s house in Pokhara, I hired a porter to carry my luggage and walked home to Dhampus. That evening, after having freshly cooked chicken and rice, we gathered in the middle of the house and opened up a suitcase that was filled with new clothes and gifts for everyone in the family. The joy and excitement those gifts brought my family were beyond words; I still remember that day as if it was just yesterday.

The village life didn’t appeal to me at that phase of my life, so I spent my entire long-leave at Pokhara, learning to type and taking extra English classes.

After rejoining my regiment in Brunei, I attended the Junior Leadership Cadre course and did pretty well, qualifying for a promotion to Lance Corporal.

By 1985, we had already returned to Hong Kong after our regiment’s two-year tour in Brunei. I then got an opportunity to go to the UK for a year. It was a coveted opportunity that all of us desired. Needless to say, I was delighted, but there was a problem. I was still unmarried and the pay gap between married and unmarried soldiers was quite substantial. Thankfully, there happened to be a solution. It might sound unusual nowadays but it used to be normal practice back then, and we didn’t see any problem trying.

We could apply for a two-week holiday at our own expense, come to Nepal, find a girl, bring her to the British Gurkha camp in Kathmandu, register her as your newlywed spouse, and return to Hong Kong to resume your soldiering duties. You would have plenty of time to fall in love and have children later. But in the meantime, the new couple would start communicating through letters, as the internet, email, and chatting were still decades away.

That was exactly what I did and I was not alone.

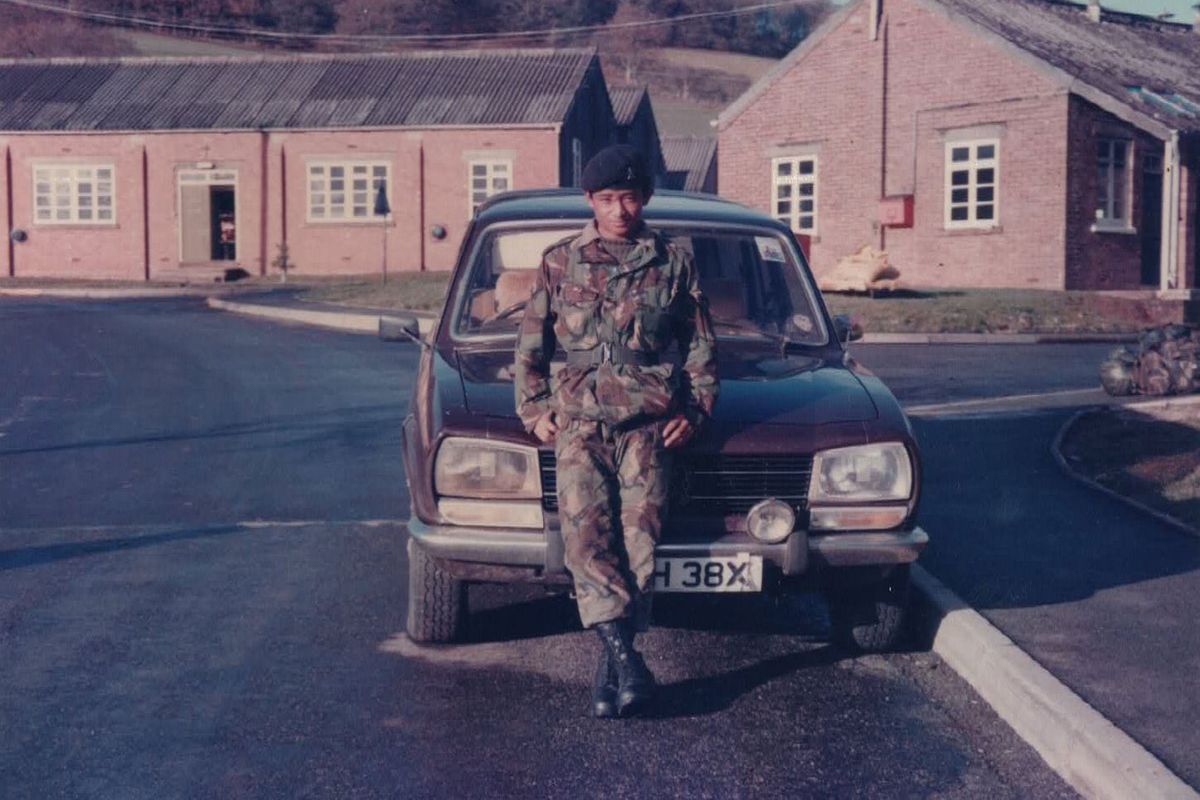

After getting married, I duly moved to the UK, where my unit’s job, as the Demonstration Company, was to provide military and administrative support to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst where all the British officer cadets trained.

In my initial days, I was intrigued by the timing of the sunrise and sunset in the UK. In the winter, the sun rose late after 8am and disappeared before 4pm whereas in the summer, the sun came at four in the morning and didn’t go down until 11 at night. We used the extra daylight to go out and play football after dinner in the summers.

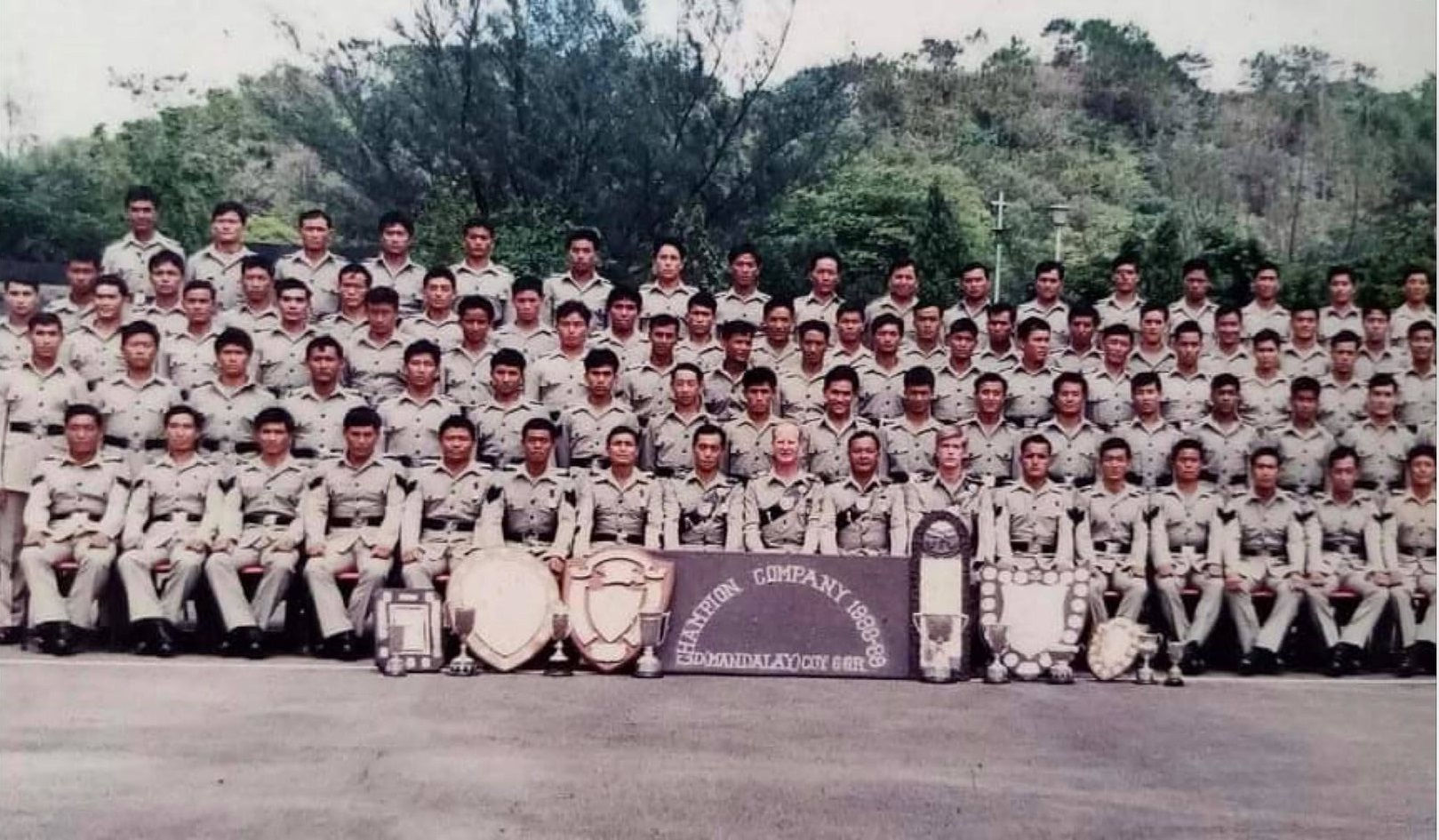

Men from the west and east of Nepal had separate regiments, at least in the infantry battalions. However, corps units like the Gurkha Signals, Engineers, and Transport had men from both west and east Nepal. Each regiment had its own medical, primary school, and a NAAFI (Navy, Army, Air Force Institutes) shop. The Gurkha Brigade had one central high school for the older children with civilian teachers and midwives hired on a contractual basis from Nepal.

Each regiment also had its own Hindu pundit and a temple. Most Hindu rituals and festivals such as Dashain and Tihar were performed accordingly. There was also a dedicated radio station, BFBS, and a weekly magazine called Parbate for the forces. Most of the office work was handled by the clerk platoon, also known as Babujis, who all came from Darjeeling.

Just like all the other communities, we also had a variety of soldiers. We had superstars, sportsmen, shooters, bluff masters, pretenders, sly and cunning ones, opportunists, drinkers, the smart and intelligent ones, and the average Joes. But army rules and regulations were very strict. Serious offenders were packed up and sent home empty-handed right away. Army wives had to wear saris whenever they went out of the camp. As a result, disobedience, insubordination, thieving, and adultery were almost nonexistent.

After a one-year stint in the UK, I returned home for my second long-leave, and that was when I got properly married. We bought a one-story house in Bagar, Pokhara from the money I had saved. We own that house even today.

When it was time to go back, it was my regiment’s turn for a two-year tour in the UK, but I chose my family over the money I would make and remained in Hong Kong. My wife joined me a few months later and both my children were born in Hong Kong.

After two years, my regiment returned to Hong Kong and I rejoined them. But to my utter surprise and disappointment, my regiment wasn’t the same one I had known. It had turned into a completely different, unfamiliar unit in my absence. The brotherhoods, comradeships, trust, and care we used to have were all gone and I felt like a stranger in my own house. People seemed cold, everyone acted differently, and I started to feel lost. As a result, I struggled to fit in, suffered emotionally, and lost my bearing.

Whether it was them or me who had changed, I still don’t know for sure. But one thing was certain, my days in the army were numbered and the countdown had already begun.

I came home for my third long-leave and returned to Hong Kong without my young family. By then, I already knew I wasn’t cut out for the army life and started thinking about a life outside the army. I did just enough to discharge my duties in the army while spending more time reading books, newspapers, and acquiring general knowledge of the outside world. Luckily, I had done extra courses on first aid, map reading, and basic Cantonese, which became pretty handy in the later stages of my army days. I was given the responsibility of teaching young soldiers these subjects whenever they had no other important classes to attend in the afternoon. I also worked as an assistant to education instructors in the 28 Army Education Centers where we helped young British officers who had just joined the Gurkha Brigade practice their Nepalis, or as it was called ‘Gorkhali’.

With 1997 approaching fast, the British were readying to leave Hong Kong. We had altogether 10,000 men and their families in Hong Kong at that time. But the process of trimming down had already begun within the Gurkha Brigade and the British were introducing tough rules and training to weed out the weaker ones. One of the infamous routines was the long march, where soldiers were required to march long distances almost daily, carrying sand pouches and bricks on top of their army equipment and weapons. We sustained bruises, blisters, and backaches. Those who couldn’t endure the long marches were earmarked for redundancy.

Two-thirds of the total forces were made redundant and sent home before the British left Hong Kong. Only 3,500 out of the 10,000-strong forces went to the UK. My last post in the army was as an education instructor at the training depot where we taught basic education, including map reading, to the new recruits. Since I didn’t get to go to the UK with my regiment, I got family permission as compensation and my wife and children joined me in Hong Kong for the second time. When I got my last marching order from the army, we had just been in Hong Kong for 10 months. I didn’t even have enough money to pack my bags.

After 13 years of service in the British Army, I finally boarded a plane with my young family in late February 1993 to return home. I was a 30-year-old army corporal when I retired with an early pension.

Back in Nepal, we also had to attend a month-long resettlement course at the British Gurkha camp in Kathmandu before we could go home as civilians. I had applied for journalism with a daily in Kathmandu called Deshantar. After meeting the editor-in-chief with a gift, he dismissed me instantly, and I never saw him again.

Every day, for the entire next month, I took a bus to Ratna Park after my morning meal and wandered around for the whole day, taking the same bus to return to camp in the evening. I did nothing that whole month, let alone writing. I felt like the editor and his staff must have taken me as a joke. After all, I was just a lahure — simple, thick-headed, and naïve.

Eventually, I found a job at an international firm based in Hong Kong as a Quality Controller. My duties were to visit China weekly and deal with products made in various factories around southern China.

But that job and what inspired me to start my own business in the year 2000 is a story I will tell in the next iteration of this column.

Tim I Gurung TIM I GURUNG is a novelist, an ex-Gurkha, author of Ayo Gorkhali, an acclaimed book about the Gurkhas. He lives in Hong Kong.