Features

10 MIN READ

With many of Nepal’s art and artifacts being repatriated, questions still remain about how those antiquities left the country and what will happen to them when they come home.

This year alone, more than half-a-dozen Nepali artifacts have been returned by museums and collectors across the world. These include an 800-year-old Laxmi Narayan statue, a 13th century carved temple eave, a 14th-century gold seated Buddha, a 15th century Ganesh, and a 13th-century Chaturmukhi Shivalinga.

“In the last few years we have also received statues of Diwakar Buddha, Garudasan Buddha, Saraswati, and 20 idols stolen from a monastery in Dolpa,” said Sarita Subedi, an archaeology officer at the Department of Archaeology. “Repatriation of lost artifacts has taken place from countries like Germany, Austria, and the United States.”

These statues, often hundreds of years old, are largely being identified in foreign collections by citizen-led groups like Lost Arts of Nepal and the newly established Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign. As the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act makes it illegal for any antiquities more than a hundred years old to be removed from their places of institution, many of the Nepali artifacts that are in museums, galleries and private collections abroad are believed to have been taken illegally. Nepal also ratified the UN Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property in 1976.

“There is a feeling of disappointment when you come across your cultural heritage in the museum of a foreign nation,” said Alisha Sijapati, a former reporter for Nepali Times who actively reported on a number of repatriation efforts. Sijapati is a founding member of the Nepal Heritage Recovery campaign (NHRC), an organization dedicated to bringing back Nepal’s lost and stolen heritage from foreign lands.

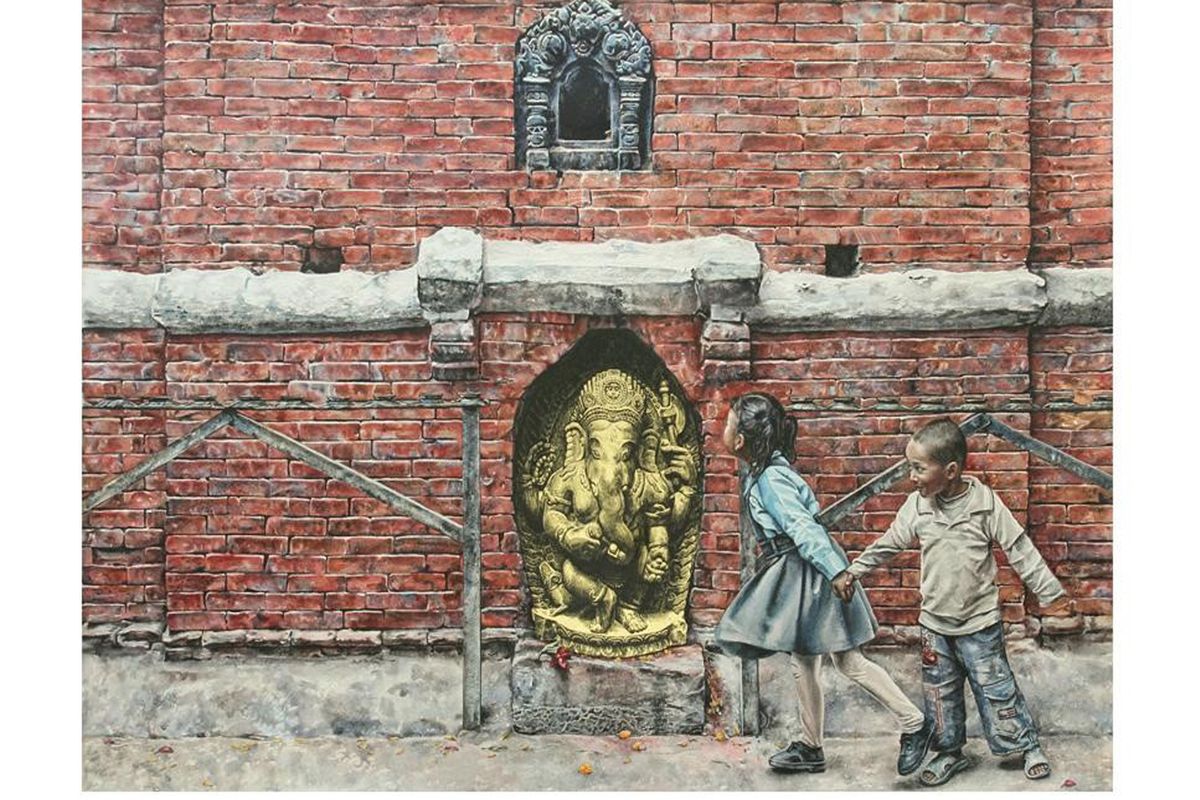

Groups like the NHRC, armed with extensive catalogues like Lain Singh Bangdel’s Stolen Images of Nepal and the artist and scholar Joy Lynn Davis’ stunning paintings of stolen artifacts, are now actively pursuing the repatriation of these stolen gods. They reach out to the Department of Archaeology, which initiates the repatriation process.

“The Department of Archaeology, which is under the Ministry of Culture, coordinates with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to initiate the repatriation process,” said Subedi. “The embassy of the concerned country is then contacted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to begin negotiations.”

Artifacts and antiquities make up an intrinsic part of a nation’s culture, especially for a country like Nepal where these objects are not just inert things to be seen in a museum; all-too-often, the statues and artifacts were idols that saw regular worship before they were stolen. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Life both guarantee an individual’s right to take part in culture or religion, which are manifested through artifacts or sculptures.

“But cultural rights are still not prioritized as much as civil and political rights,” said Sanjay Adhikari, an advocate and also a founding member of NHRC. “Organizations like the National Human Rights Commission should have actively taken part in the repatriation of lost and stolen artifacts.”

The question, however, remains: how did these Nepali artifacts leave the country in the first place?

Although there are many theories and conspiracies, there is little hard evidence to go on. Everyone from the Rana oligarchy, the former royal family, and the later crop of politicians in democratic Nepal are said to have been involved at one time or the other.

Historian Gautama V. Vajracharya writes that Nepali artifacts were first stolen in the 16th century. He cites an 18th-century inscription that describes the theft of a statue of Narayan in 1765. According to historians like Vajracharya, art theft only began with the entrance of the British to India.

Previously, such artworks were only seen as objects of worship, not of interest to collectors and museums. It was the British that began to cart away artifacts by the truckloads from the countries they colonized.

But Nepal was never colonized by the British and remained largely closed-off to the world until the collapse of the Rana regime in 1950. It was then that foreigners began to arrive in Nepal and an interest in Nepali art began to take hold.

According to historian Mahesh Raj Pant, in 1967, interest in Nepali art arose after king Mahendra sent Nepali artifacts to New York for display at the Asia House Gallery. The exhibited artifacts were later brought back, but they would introduce the international art market to Nepali craftsmanship and create a large demand that would be met illegally.

“Later, German art historian Stella Kramrisch published a book called Art of Nepal, which was based on the same exhibition, and this attracted westerners to Nepali artifacts,” said Pant. “Art historians themselves have played an important role in getting our artifacts stolen and displayed in foreign museums.”

Mary Shepherd Slusser, a scholar who authored numerous books about Nepal and Nepali art, herself admitted to acquiring six Nepali paintings when she arrived in Nepal in the 60s with her USAID-employed husband. In an article published in 2003, Slusser recounted acquiring six paintings for a few hundred dollars each. She admits herself: “it being illegal (theoretically) to export genuine antiquities.” Five of those six paintings ended up in the Virginia Museum of Art.

In the same article, Slusser again recounts obtaining a painting for a Japanese diplomat on the condition that he spend whatever necessary to preserve it. The logic being that “the poor condition to which it had succumbed by 1967 in its homeland is perhaps the most cogent argument in support of collectors and collecting: had it not been for the intervention of the art market, this important painting otherwise seems to have been slated for an ignominious end in someone's dustbin.”

A 2018 Al Jazeera documentary titled Nepal: The Great Plunder also showcases how artifacts were smuggled or sold. The video sheds light on how easy it was to illegally obtain ancient artifacts. In the documentary, the seller can be seen time and again assuring customers about the export of the artifact.

“Don’t worry about customs. It is illegal but I can manage. I can fix the deal under the table,” says the seller. What is even more interesting is the fact that the seller has connections with museums abroad.

According to Roshan Mishra, director of the Taragaon Museum, Nepali artifacts also left the country as gifts to foreign diplomats and envoys. Vajracharya, in his Himal article, writes that king Mahendra presented a 12th-century metal sculpture to Canadian ambassador Chester Ronning as a gift.

But Mishra believes that it is more important to focus on getting the art and artifacts back to Nepal, rather than how they were stolen in the first place. However they got there, he believes that museums and collectors will begin voluntarily returning artifacts to the country of origin within the next 15 years.

“Discussions on ethical sourcing and decolonization have started all over the world,” said Mishra.

That process appears to have already begun. According to Adhikari, the NHRC has already received more than 20 emails from private collectors all over the world inquiring on how they can return artifacts acquired by their predecessors.

“People have become conscious of the link between artifacts and human emotions and rights,” said Adhikari.

But Mishra says that it is not enough to simply repatriate ancient objects.

“It is high time we shift the conversation toward how we as a country of origin are going to manage our returned artifacts,” he said. “Is it possible for us to preserve and restore them to their original place?”

Contrary to public perception, the Department of Archaeology’s Subedi asserts that Nepal has the capacity and human resources to preserve returned artifacts. Many in the public sphere have been concerned about the objects collecting dust in some storage room, gradually deteriorating in the absence of proper preservation methods. This is not an unreasonable perception, as Slusser asserted in her 2003 article. Images and newspaper reports of ancient manuscripts ruined and lying in pitiful states do not help instill confidence in the Nepali state’s ability to preserve antiquities.

Subedi, however, was adamant that the Department of Archaeology did not lack technical “manpower”or technology such as temperature-controlled rooms in which to store the antiquities.

“If the statues are damaged, they will be treated by engineers and put on display,” said Subedi.

An additional complication with repatriated Nepali artifacts is that most of them are ‘living’ objects; before being removed from their places of origin, they were often visited and worshipped by local communities, forming an essential part of the local cultural fabric. Locals might not have the wherewithal to keep the artifact protected and it could be stolen again.

“Once an artifact is brought back to the country it is thoroughly examined and restored to its original place,” said Subedi. “We hand it over to the local body, but if the locals feel uneasy with the protection of the artifact, it is then referred to a museum.”

Section 4.3 of the Ancient Monuments Preservation Rules states that every year, local officers shall create an inventory and send descriptions of archaeological objects to the chief archaeological officer.

“If this rule was followed thoroughly, we could reduce the chances of our artifacts getting stolen as we would have descriptive inventories,” said Adhikari of NHRC. “The Department of Archaeology does not have any inventory created by local officers.”

There is also the argument that in a globalized world, it doesn’t make a difference whether an artifact is in a museum or its country of origin, as long as the artifact in question is preserved and put on display for everyone to see and appreciate. But according to Amr Al Azm, associate professor of Middle East History and Anthropology at Shawnee State University, artifacts are a cultural property that reflect the history, nationality, and identity of the nation and its people; they are symbols of national pride.

In an Al Jazeera documentary titled ‘Who owns ancient artifacts?’ Azm reiterates that an artifact can only reach its true potential value in in situ preservation. If you take an artifact out of the context in which it originated, it becomes just an inanimate object.

“When we talk of repatriation and place of origin, it doesn’t simply mean bringing back statues or artifacts to the country and displaying them in museums,” said Adhikari of NHRC. “Repatriation has to be understood in a wider sense where the returned statue or artifact is used by the community. For us Nepalis, statues are not showpieces but gods and goddesses who play a vital role in the life of the community.”