Longreads

Features

20 MIN READ

Changing migration patterns mean that more Nepalis are now traveling to western Europe via dangerous, illegal routes in the hopes of obtaining residence in a European country like Portugal.

ODEMIRA, PORTUGAL – In mid-March, Dharam Lal Das woke from a deep sleep feeling parched and nauseous. His vision was blurred and all he could make out were the light bulbs on the ceiling. Before he could bring the rest of the hazy objects in the hospital room into focus, he felt a burning sensation spreading from his hips all the way to his feet.

His heart sank. He thought his legs were gone.

No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t recall what had happened to him and how he ended up in hospital.

That emptiness and inability to piece together what had happened to him lasted beyond the nearly two weeks that he was in a coma at a hospital in the Croatian capital of Zagreb.

Over the next few days, he slowly started recognizing people who came to meet him. And soon enough, the flashing memories of crossing thick jungles, climbing hills, falling to the ground, screaming for help somewhere on a highway, getting on a police van, and then being taken to a hospital came into sharper focus.

He says it was hard for him to process what had happened to him given the present condition that he was in – plugged into tubes and oxygen in Croatia, a country where he had arrived less than two months ago, chasing dreams of a better future.

***

Like the countless Nepalis leaving the country each day, Dharam Das, too, embarked on his journey to Europe brimming with hope. There was a tinge of nervousness as he left his hometown in Janakpur last January for Kathmandu and took his very first international flight to Croatia, a country little-known to many in Nepal, located on the Adriatic coast, to the east of Italy.

And just like that Das became another statistic in the ever-increasing number of Nepalis who have trickled steadily to this Balkan country in the last six years.

According to the Department of Foreign Employment, until 2014, no work visas had been issued for Croatia. But since then, that number has increased exponentially, going from zero to six in 2016 and climbing to a massive 1,087 just four years later in 2020.

When Das was looking to go abroad, Lalit Yadav, an agent in Janakpur, told him about Croatia, a country in Europe, where more and more Nepalis were easily getting visas and work permits. Das said that was the first time he had even heard of the country. He looked up Croatia on YouTube and saw videos of the blue sea and old forts.

It looks like a nice place, he thought and started the application process, which would eventually set him back nearly Rs 1 million.

After several months of waiting, a deadly second Covid wave, and subsequent lockdowns in 2021, Das finally got his visa and headed to Croatia in January this year.

As the oldest son and the first person in his family (and his entire neighborhood, according to him) to go to Europe, he said he knew the great expectations on his shoulders to make the most of this opportunity.

He began his job at a transportation company in Croatia a few weeks after landing in Zagreb. But he soon realized that the promises of a well-paying job that Yadav, his agent from Dulsco Human Resource in Dhumbarahi, Kathmandu had made were a sham.

Das had taken a loan of Rs 800,000 to pay the manpower company in Kathmandu. The agent who had helped him land the job had told him he would be able to save enough to easily make more than Rs 200,000 each month. That was a lot more than what he was making in Janakpur with a degree in mechanical engineering.

“I thought it was a good deal, and I would save enough to pay back the loan in no time,” he said.

But what he received was less than Rs 100,000, with no overtime, and payment that came 15 days after the end of the month.

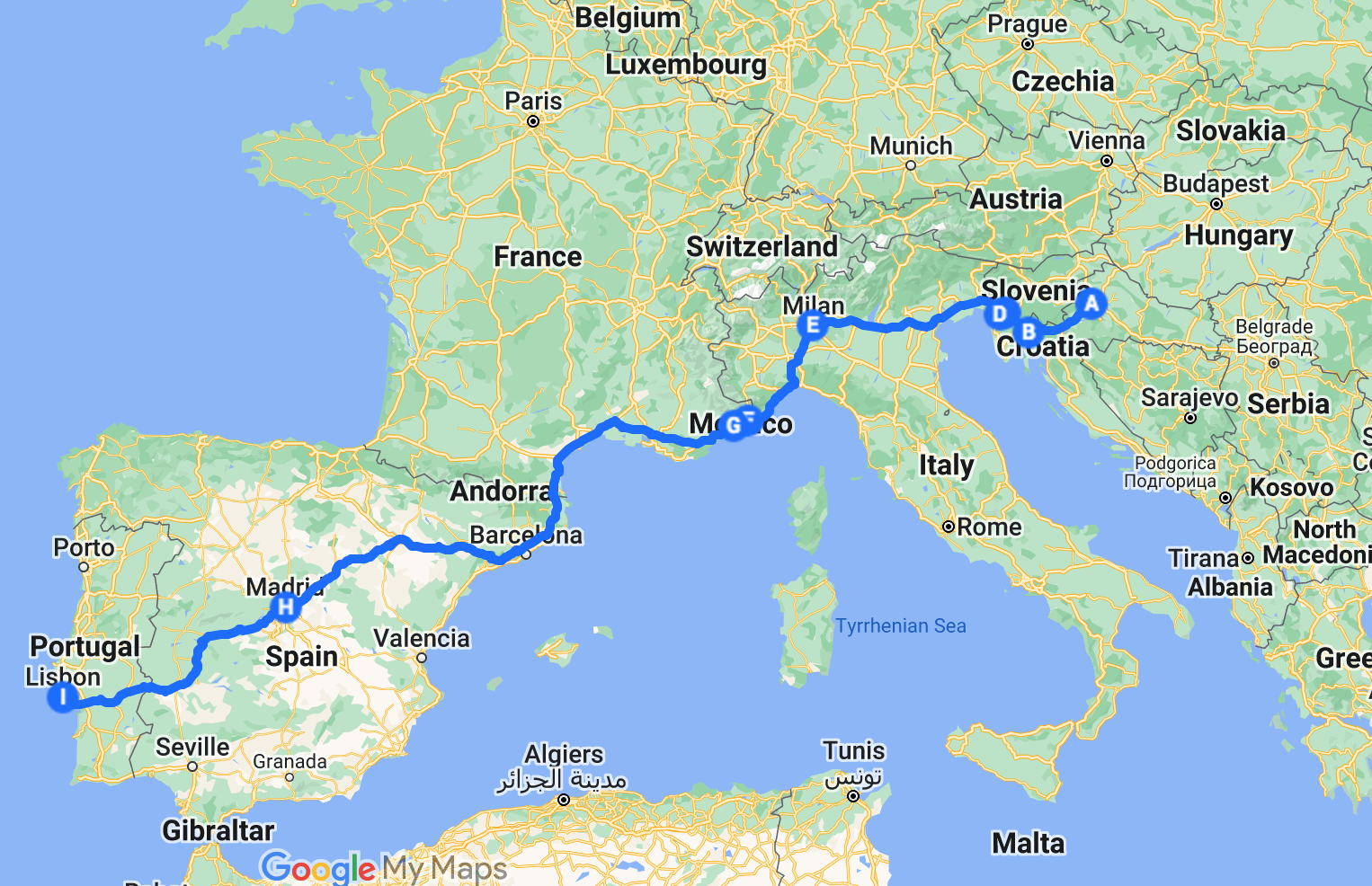

He had been staying at a hostel at that time and hadn’t even cashed his first month’s paycheck when he bumped into a group of Nepalis. There, for the first time, he heard stories about how Nepalis were crossing into Slovenia from Croatia, walking for days crossing jungles, highways, and hills, and making their way through Italy, France, and Spain to Portugal.

Croatia is part of the European Union but not yet part of the Schengen area, which allows document-free movement throughout the region. They would have to cross the border into Slovenia and Italy illegally. The journey wouldn’t be easy but in Portugal, according to his new friends, jobs were plentiful, the pay was better, and there was an easy pathway to permanent residency, which would open avenues to bring his family over.

“I was sold on the possibility of better money and bringing my family to Portugal,” he said. “After all, I had come so far chasing money and a better future.”

So on a cold March morning, less than two months after landing in Croatia, Das joined eight other Nepalis, carrying only a change of clothes, some dry fruits, energy drinks, water, and his passport in a small backpack, and began his trek towards the Croatia-Slovenia border.

The group took a bus from Zagreb to Rijeka in western Croatia and stayed the night there. The next evening, as it started getting dark, they began walking further up north, away from the port city of Rijeka and towards the dense forests and hills that would lead them across the border to Slovenia.

All this while, they were being guided by a Nepali agent, who didn’t reveal his identity and was only communicating through WhatsApp, sending them maps to navigate the darkness of the forest at night. That agent was responsible for taking them across the border to Slovenia, Italy, and further westward to France, Spain, and finally Portugal.

More than 48 hours had passed since they had left Rijeka. Maybe it was the non-stop walking, the cold of the night (Das said it was also snowing lightly), and his empty stomach but soon his body started giving up and he couldn’t keep pace with the rest of the group. They had just crossed a highway and had begun climbing yet another hill in pitch darkness when he started having trouble breathing.

His friends didn’t want to stop so close to the highway fearing patrolling officers who regularly arrest and send back migrants like them. Some even volunteered to carry him for the rest of the journey, assuring him that they were only a few hours away from Italy, after which they would easily be able to board a bus or a train to go to Portugal.

“But I knew this wasn’t possible given the terrain we were in,” he said, “I told them repeatedly that I wanted to go back but no one was willing to let me do that.”

Between struggling to breathe and pleading with his friends to let him go back, he says he wasn’t fully able to comprehend what was happening.

What he does remember is that the discussion soon became heated. Someone from the group snatched his phone and deleted the WhatsApp group with the agent who had planned this trip. He thinks he heard the others suggesting they beat him up and leave him to die so he wouldn’t reveal anything to the police if he was found.

“I was in and out of consciousness but I remember feeling very scared about what was happening to me,” he said.

The others began to coax him by saying that a group of Nepalis, including some women, had just made it across the borders of Italy.

“If women were able to make it across the several day-long trek, I too had to muster the courage, they told me,” he said.

He was a healthy, well-built 32-year-old, weighing just over 80 kgs. He thought he had it in him to take the plunge.

But today, when he looks at his sunken eyes, hollow cheeks, and skinny limbs, he deeply regrets his decision.

***

The first time he saw himself in a mirror, several weeks after leaving the ICU, he says he felt awful seeing his reflection. The double chin was gone and his collar bones were sticking out of the blue hospital gown. He had dropped over 20 kgs and weighed a mere 58 kgs.

“I was skin and bones and my face looked like I was 80 or 90 years old,” he said. “I felt horrible.”

The Slovenian police found Das collapsed by the side of a road near a forest leading to Italy, according to a press release from the Non-Resident Nepali Association (NRNA) in Croatia. Because he had a valid Croatian work permit, the Slovenian authorities returned him to Zagreb. It was back at the hostel in Zagreb that his health began to deteriorate and he had to be admitted to hospital. He had pneumonia that had spread to his lungs and kidneys. He was in a coma for two weeks, he says.

After nearly two months at The University Hospital of Infectious Diseases in Zagreb, his health has steadily improved. There is a minor limp in his left foot, but he says he no longer needs a stick to aid him while walking. His sagging face is starting to fill up again.

He has now moved into a house with other Nepalis, where all he does is sit in his room and pray that he is able to travel back home soon.

That is something that has been on hold since he hasn’t been able to pay the hospital bills for his extended stay and treatment. When he started feeling better and requested a discharge, he was told that his bill was around 140,000 kuna (Rs 2.4 million) and he couldn’t leave until he had cleared it. The NRNA’s Croatia chapter stepped in as guarantor to ensure that the bill would be paid after discharge and that he wouldn’t leave the country until then. The NRNA is currently trying to raise funds to pay the bill and send him back to Nepal.

“I am losing my mind because I am not able to go back to Nepal,” said Das. “It’s like I am stuck in jail.”

***

Das couldn’t make it to the finish line of the arduous trek to reach Portugal, where recent policy changes allow any migrant workers to get regularized as long as they follow the due process once they enter its border, irrespective of the means or routes they use to get there.

As a result, the number of migrants from countries like Nepal in Portugal has increased significantly in recent years. According to a 2020 report in Nepali Times, 1,287 Nepalis acquired Portuguese citizenship in 2019 – making them the ninth biggest nationality in the country.

Similarly, according to Pordata, a database tracking and compiling different indicators of Portuguese government agencies, the number of Nepalis who’ve acquired residency permits has skyrocketed in the last decade. In 2010, there were less than 800 Nepalis with resident status but in 2020, that number had swelled to 21,000.

But data from the Department of Foreign Employment shows that the total number of Nepalis who received labor permits for Portugal around that same time period, from 2013 to 2020, stands at less than 1,300.

It is hard to trace the journey of most Nepalis who reached Portugal through irregular channels. But conversations with Nepalis here in Odemira to the southwest of Portugal revealed that most Nepalis had arrived through a network of individual agents, and acquaintances, mostly arriving on tourist visas. I spoke to nearly 20 Nepalis from Odemira, Tavira, and Lisbon who had come to Portugal using similar routes. All of them said they paid upwards of 10,000 euros, around Rs 1.3 million.

According to a 2020 report from Nepal’s Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, the recruitment cost for Portugal prescribed by the Nepal government stands at Rs 65,000.

But for those who don’t secure tourist or work visas, there are more dangerous routes available, like the one Dharam Das found himself on. Every year, hundreds of people, mostly from South Asia and Africa, cross countless borders and checkpoints from eastern Europe to reach Italy and beyond, mostly Portugal because of its lax immigrant laws. Last April, two Sri Lankans lost their lives trying to cross a highway in Italy after being hit by a lorry.

I was able to meet several Nepalis who arrived in Portugal over the last eight months from countries like Croatia and Cyprus, using the same route and similar agent networks as Dharam Das did, paying anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 euros.

I spoke to a dozen Nepalis, 10 men and three women, mostly in Odemira, where almost all of them worked on raspberry farms. They recounted similar horrors of crossing on foot through thick jungles in Slovenia, running past border checks in Italy, some getting arrested in France, finding containers and lorries to carry them across borders, and finally breathing a sigh of relief upon reaching Lisbon.

Sunil and his wife Rita, who are from Kathmandu, said they couldn’t believe it when they finally entered Portugal after a harrowing nine-day-long journey that also started in Zagreb. Both of their names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Like Das, they too spent nearly Rs 1.5 million to get to Croatia in 2021. They had also never heard of Croatia, thinking it was a country in Africa.

“I didn’t even know it was in Europe, kaaleko desh ho bhanera sochey,” Sunil told me while waiting to get his paperwork done at the local immigration office in Odemira in May.

The journey, which he undertook with his wife Rita, a dozen other Nepalis, and three Indians, was the hardest thing Sunil said he has ever done in his nearly four decades of life.

“We didn’t have any water to drink for 12 hours. When we finally saw a horse stable with water, I dunked my face in the vessel,” he recalled.

He says the physical toll reached a point where it started affecting him psychologically.

“Maybe it was the lack of sleep or the fear all around, I thought the people I was with were trying to kill me,” he said.

Sunil’s experiences are consistent with that of most other Nepalis who arrived the same way. But the fact that they made it across is leading to many more attempting the same journey, which migration experts say point to a shifting pattern.

“In the last few years, there’s been a gradual shift away from traditional countries like Malaysia and the Gulf towards Europe,” said Neha Choudhary, national project coordinator at the International Labour Organization in Kathmandu who has been closely studying the Nepal-Europe migration corridor. “The profile of Nepali migrant workers is changing. Most of them now have higher aspirations and want to explore opportunities beyond and don’t want to go for construction jobs in the Gulf.”

The biggest pull factor for Nepali migrants are the immigration policies of countries like Portugal, which provides an easier path to residency in a Western country.

“For the most part of the last two decades, what we had was a circular pattern of migration, people went abroad but they came back home,” said Choudhary, “but what we are increasingly seeing now is people aiming to go to countries in Europe and staying there for good.”

But because there is so little information about new job markets in Europe and the fact that Nepal doesn’t have bilateral agreements with the countries Nepalis are heading to, the journey is dangerous, uncertain, and comes at a hefty price.

Among the people I spoke to, some had entered the country on a Schengen tourist visa, which allows free movement in 26 European countries, while others made their way on foot like Dharam Das, Sunil, and Rita after securing a work visa in countries like Romania, Malta, and Croatia. All of them said their priority is paying off the loans they took to chase the European dream.

“People are compelled to take out significant loans to fund their migration process, putting them at risk of falling into the trap of debt bondage,” said Choudhary. “They are stuck in whatever jobs they are doing, even those that don’t have decent working conditions, because they are thinking about the loan they have to pay back.”

Once Nepalis reach countries like Portugal, there are more obstacles awaiting them, from getting fair pay and decent working conditions to overcoming language barriers. Even those who go there on a valid work permit come here paying hefty fees to brokers, and don’t always get what they were promised.

Twenty-six-year-old Dhiraj from Khotang is one of them. We are not using his real name to protect his identity. He came to Portugal towards the end of 2020 as a seasonal agriculture worker, paying nearly 1.4 million rupees to an agent he refers to as ‘Sherpa dai’. But summer was already over by the time he got to Portugal, and the farm didn’t need any workers.

He spent the next three months without work. ‘Sherpa dai’ promised him that something would come up soon and arranged accommodations at cramped living quarters in Beja city in southern Portugal. Over 20 people shared the crowded apartment with a single bathroom. He was sharing a room with five other Nepalis.

“That wasn’t how I had pictured living in Europe,” said Dhiraj.

Currently, he works at a sushi restaurant run by a Nepali just outside Lisbon. But even here, he is only able to make 700 euros, the minimum monthly wage set by the government, which is much lower than in other European countries. He says his salary is neither enough to pay off his loans back home nor save anything for the future.

And while the living situation is better than before (he shares a room with another Nepali), he says he gets anxious thinking about what the future holds.

“I worry that time is passing by so quickly and I have still not been able to do much, not even pay off the loan,” he said in an achingly sad voice. “I am not even married. When will I get married or start a family?”

Kamal Bhattarai, who runs the the Lisbon-based NGO NIALP, says his small team is always overburdened with queries from Nepalis.

“There are very few who come here on work visas. Nepalis mostly come here on tourist visas or as students,” said Bhattarai. “And now, there are many more who come from east Europe.”

He says there is an urgent need for authorities in both source and destination countries to work together to make the process more transparent so people don’t fall for false promises from agents and middlemen.

“Yes, people need jobs but there should be a way to regulate these things, so people don’t have to pay exorbitant amounts of money to come to work in Europe,” he said.

Nepali authorities say they are aware of the rampant fraud cases involving jobs in Europe and that they have put in place new provisions like demanding that job contracts be certified by the concerned embassies in Europe. Shesh Narayan Paudel, director-general of the Department of Foreign Employment, says they receive a lot of complaints of job fraud in Europe and have even lodged several cases, and encourage more people to come forward.

But in the end, he says, it all comes down to individual choice.

“Many people pay so much to middlemen and agents despite knowing the risks and uncertainties. They need to be more responsible,” Paudel said. “People blindly pay hefty fees, upto ten lakhs sometimes, and as long as it gets them to Europe, they are fine. If they don’t reach Europe, they reach out to us for help.”

Even Nepalis who’ve recently arrived in Portugal have now come to realize that the country is not all it was promised to be.

“Portugal is the khaadi (Gulf) equivalent of Europe. It’s a lot of hard work here,” said 27-year-old Prabin from Mahendranagar, who also asked that he not be identified by his real name. He also works on a raspberry farm in Odemira and shares a three-room home with five other Nepalis. He and his wife make just over 1,000 euros each month.

“We didn’t know what we had signed up for when we decided to come here,” Prabin’s wife Priya, also not her real name, said. “I don’t even want to think of those two weeks we spent on our way here. It’s not as easy as others make it out to be, it was like a horror movie.”

And that is something Dharam Das in Croatia cannot reiterate enough. In a video posted to the NRNA’s YouTube channel, he pleads with others not to fall for the European dream. There are increasingly more migrant workers like him who are taking to social media, through Facebook and YouTube to warn others after being duped by agents into low-paying jobs in countries in eastern Europe.

But alongside those same warnings, there are countless posts from others asking how they can get to Croatia, or how they can go to Portugal from countries like Croatia.

Experts like Choudhary say that there is a lot of prestige attached to going to Europe, and because they pour so much money to get to countries like Portugal, they are hesitant to talk openly about their arduous journey or even the terrible work conditions they might be facing.

Sunil from Kathmandu, who made it all the way to Portugal to pick raspberries, doesn’t tell his family what he does for a living.

“How can we tell them we toil all day on farms with just enough to pay back all the loans?” he said, without fully disclosing how much he gets paid. “They think it’s Europe so we must be doing well, and we want to keep it that way.”

***

With additional reporting by Fabian Federl. This report was made possible with support from journalismfund.eu

Longreads

Features

20 min read

Changing migration patterns mean that more Nepalis are now traveling to western Europe via dangerous, illegal routes in the hopes of obtaining residence in a European country like Portugal.