Features

7 MIN READ

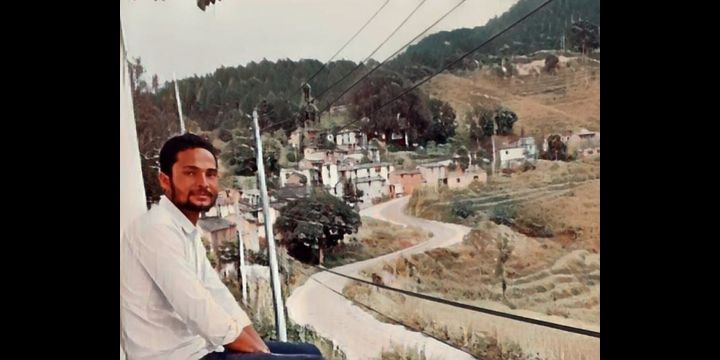

Siddhartha Aahuji would still be alive today if two hospitals had valued his life

Sidhhartha Aahuji had told some of his friends that he would immolate himself if his employer, Bayalpata Nyaya Hospital, did not withdraw its decision to fire him and his colleagues. They thought he was joking. He was not. On June 8, to protest the hospital’s layoffs, Aahuji soaked himself in petrol and set himself on fire.

“He was engulfed in flames for more than half a minute, till two civil cops and hospital employees extinguished the fire with blankets,” said Inspector Ramesh Awasthi, a local police officer investigating the case. Sidhhartha died later on the same day for lack of treatment.

In May, the hospital had announced it would lay off some of its temporary non-medical staff on July 15, citing shrinking aid from donors due to the Covid-19 crisis. A cleaner at the hospital, Sidhhartha was both angry and worried. Although some workers readily quit their job and left for their homes, Sidhhartha and some of his colleagues had been protesting against hospital management.

“Since the hospital had given notice more than a month before the dismissal date, they were hopeful that the hospital would rethink its decision if pressed hard,” said Awasthi.

Bayalpata is a hospital run by Nyaya Health Nepal, a not-for-profit organization that has been lauded for promoting community-centric public healthcare in countries like Nepal, where a vast majority of people don’t have access to health services. Bayalpata, for example, provides free health facilities to thousands of poor people in Achham, one of the least developed regions in the country.

The decision to fire workers in the middle of the Covid-19 crisis had not gone down well with the local stakeholders as well. On May 27, Sanfebagar Municipality had urged the hospital against taking any such harsh step. Kul Bahadur Kunwar, the mayor of Sanfebagar Municipality, said that during a meeting with hospital administration on June 1, the hospital had agreed to not fire its employees.

“We agreed to find a solution to address the financial crisis, in coordination with the local, provincial, and federal government. It was agreed that the hospital would withdraw its decision,” said Kunwar.

It’s unclear whether the hospital was truly going through a financial crisis or acting on the whims of a reckless management, as some insiders claim. But the hospital remained adamant about not budging from its decision. And although Siddhartha’s family had not discerned any ominous signs in his behaviour, he had made up his mind to immolate himself.

He had done all the preparation before going to the hospital, at 8:27 am. Once he reached the hospital, he stopped in front of the emergency ward, took out a bottle of petrol from his bag, and lit himself with a lighter. Family sources said that he had also consumed alcohol.

Siddhartha, who came from a poor lower-middle-class family, was born in Accham and grew up in India, where the rest of his family work. His family has some ancestral land in Achham, enough for him to survive on. But the job meant much more than just a job to him. It had given him some financial stability and a sense of freedom. His earnings were also vital for running the family of four. Moreover, Sidhhartha took great pride in his being able to work in his ancestral village.

“He was selected from among dozens of other candidates following a written examination. It wasn't like he got the job through political influence,” said Manohar, his brother, who works in India with his parents.

Sidhhartha used to earn around NPR 19,500 per month. He wanted his parents and brothers to return home and farm, instead of working in India.

“He would often say, ‘You folks should come home. I will take care of the family expenses,” Manohar recalled in an interview with The Record. “His earnings were much better when he was working with us in India before, but he decided to come to Nepal because he wanted to do something in the village.”

Inspector Awasthi said that Siddhartha, in a desperate bid to press the hospital, may have underestimated the risk of self-immolation, thinking the doctors might save him.

“He ran straight into the emergency ward after setting himself on fire. He may have thought he would not die. Or, maybe he just wanted to die,” said Awasthi.

The hospital’s reckless decision might have pushed him over the edge, but interviews with family members, eye witnesses, and police officials suggest that multiple other factors, including outright negligence, contributed to his death.

“I think negligence by Bayalpata Hospital might have played a role in his death,” said Manohar. “He should have been admitted to the ICU after the immolation. But if you watch the videos that were recorded on the phone that day, you can see him lying unattended on the ground.”

Siddhartha could not get the required medical care in Bayalpata partly due to the hospital’s not having adequate staff and resources. After being provided basic treatment at the hospital’s emergency facility, Sidhhartha was flown in a helicopter to Nepalgunj.

The helicopter, whose flights were sponsored by the government, had come to take away Nirmala Khadka, a woman in her fifth month of pregnancy who was suffering from a swollen abdomen. (Khadka, who would later undergo an intestinal operation, has since been discharged).

Sidhhartha’s condition was already getting serious by the time the helicopter landed in Nepalgunj, according to Min Bohora, a neighbour who had volunteered to take Sidhhartha to Nepalgunj. He was then rushed to Nepalgunj Medical College, Kohalpur.

Given the seriousness of Siddhartha’s case, one would have expected the hospital to readily admit him. But he and those with him were first made to undergo a Rapid Diagnostic Test for Covid-19. The tests showed them positive for the virus, although further tests proved that the RDT results were incorrect.

“The way they were dealing with us suddenly changed after the positive tests,” said Bohara. “The hospital staff started running away from us. We were treated as if we were the coronavirus.”

Instead of admitting him, Siddhartha and Bohora were locked inside a small, dark room with only one window. Nobody opened the door for half an hour, even though Bohara was relentlessly pounding on the door. Siddhartha died inside the locked room, where he wasn’t even provided water, let alone medical attention.

“I still get nightmares thinking about that episode,” said Bohara. “He would have lived had they given him immediate care.”

Following outrage over the incident, Bayalpata Nyaya Hospital has agreed to pay NPR 500,000 and provide a job to Sidhhartha’s wife, Gauri, who has just turned 18. In addition, Sanfebagar Municipality has also announced a relief package of NPR 200,000 to support his wife and two children, according to family members and police.

The Aahujis are grateful for the relief, which they hope to use toward the education of Sidhhartha’s two kids.

But they cannot stop thinking about how Siddhartha would still be alive if the hospital had been considerate enough when he was pleading with the administration to not fire employees.

The family also wants answers to many questions that remain unanswered: What forced Sidhhartha to take such a drastic step? Was it a case of abetment of suicide? Where did Siddhartha get the petrol? Whom was he drinking with? Why didn't he tell anything to any family members before immolating himself ?

The full truth might never be known, as the family now remains undecided over filing a criminal case.

Inspector Awasthi suggested that the police have closed the case:

“We haven't been able to decide what good a case would do, given that he cannot be brought back now.”

The Record We are an independent digital publication based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Our stories examine politics, the economy, society, and culture. We look into events both current and past, offering depth, analysis, and perspective. Explore our features, explainers, long reads, multimedia stories, and podcasts. There’s something here for everyone.

COVID19

Perspectives

7 min read

In Nepal, and other parts of the world, domestic workers are routinely denied social and labor protection, and with Covid-19, their problems have only gotten worse.

Features

11 min read

Patterns of negligence, alleged abuse, and impunity in Nepal Police

Features

17 min read

The decision to build new headquarters inside Teghari Forest has divided politicians, locals and environmentalists in Sudurpashim

Longreads

Features

19 min read

Nepal’s mainstream feminist movement must go beyond class, caste, and gender to embrace intersectionality and encompass diversity in all its forms, say feminists.

Features

6 min read

Women prisoners struggle with the difficult choice of sending their kids away or bringing them up in a milieu that could negatively impact their child’s development

COVID19

Explainers

5 min read

Already marginalised by the state, the Dolpo people are more vulnerable to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic

COVID19

Features

6 min read

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought the tourism industry to a grinding halt and among those most affected have been thousands of porters.

The Wire

Features

9 min read

Slavery is the new normal for migrant workers, our reporter discovers in Qatar