Writing journeys

9 MIN READ

Writer Amish Mulmi provides a running analogy for his writing in this week’s Writing Journeys, while also handing out sound advice on how to write well.

In this week’s Writing Journey, Amish Mulmi takes a slightly different approach than the other authors and storytellers. He describes part of his writing process — how he clears his mind and sorts through writing problems while running — and offers a number of thoughtful suggestions.

His suggestions are good ones: “be patient, stay on track”, “read widely”, “never put your heroes on a pedestal”, “don’t fall in love with your first draft”, “write because you want to”, “find a schedule that works for you”, and “learn to see the world beyond your silo.”

I love the warning about “falling in love” with your prose. I have lived this problem. I used to hate cutting my hard-earned words, no matter how boring and unimportant. Words never come easily to me. If I found some good ones, ones willing to hang out with me, I wasn’t going to say goodbye quickly.

That, of course, is a big mistake. For clear concise writing, cutting may be as important a skill as weaving words together. Maybe more important. As with love, sometimes the wishful thinking – your big hopes – can distort a clear eyed view of reality. If in doubt, say goodbye.

Amish also describes running for exercise as a way to clear his mind and sort through writing puzzles — which I also do — but also, interestingly, as a metaphor for the writing process itself. One of his lines stuck in my head: “You cannot sprint long distances.” My graduate advisor used to say that writing a PhD dissertation was like running a marathon: it required good pacing and planning for the long haul. I like Amish’s advice to “remain calm” on the long runs. It’s easy to panic.

Amish mentions that the writing journey often takes place alone. That’s true. No one can run those miles for you. And you need to find your own arguments, your own style. But I wouldn’t take this too far. Writing isn’t just lone marathoners out on the trail by themselves. There’s a social side, too: brainstorming ideas, sharing drafts, discussing writing strategies. I also run. After I joined a group of runners who ran several times a week, my running improved significantly. I could compare notes. I pushed myself harder. And it was just more fun.

These essays themselves are an example. Sharing our individual journeys helps everyone move closer to their own finish lines. Thanks to Amish for sharing some of his journey and reflections!

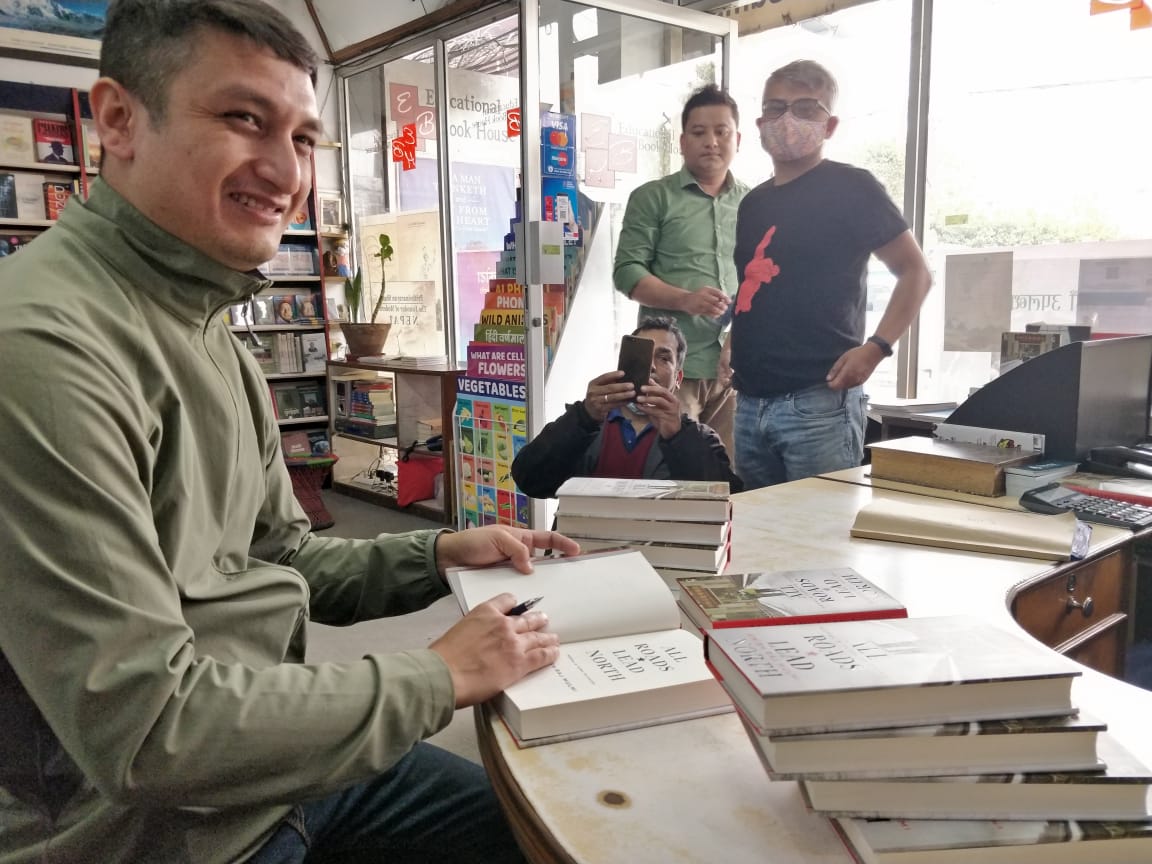

Amish Mulmi has been a columnist with The Kathmandu Post since 2018. His first book, All Roads Lead North: Nepal’s Turn to China, was published in 2021. His essays and features have appeared in Al Jazeera, Hindustan Times, Roads and Kingdoms, National Geographic Traveller (India), Himal Southasian, Mint Lounge, India Today, The Wire, and Scroll.in.

***

Running and writing

I started running one evening in 2017 as a break from being cooped up inside our apartment in Delhi. I had just quit my job at a publishing company and was now a ‘freelance editor and writer’. The fears of an unknown career trajectory haunted my thoughts as I sat at my writing desk, facing an aquamarine wall in an apartment that barely got any light. Siri Fort Park was a 10-minute walk away and despite Delhi’s heat and pollution, running seemed to be the best way to clear my thoughts.

That first day, as I huffed and puffed after a five-minute jog, my mind went blank. All I could feel was pain, in muscles I didn’t know existed, in ways that seemed physiologically impossible. As I walked out of the park, I doubted I would ever run again.

The next day, I returned. Then, the day after. Four years later, I continue to run.

Most beginners give up running because it seems too damn hard. A kilometer feels like 10 when you start. Your lungs feel like they are on fire. Your heart might jump out of your mouth. And your legs want to murder you for putting them through the strain. But running is mostly about patience and perseverance, not speed. You cannot sprint long distances.

Instead, you have to find a pace that is just right for you. You have to keep running, you have to think past the pain, the seconds and the minutes. Only then, at the end of 30 minutes, will you have done five km. Only then, at the end of an hour or two at your desk, will you have written a thousand words.

To me, running and writing are conjoined twins. My writing feeds off my running. As my legs go the distance, my mind begins working on the puzzles I face in my writing: How to start a chapter? How to frame an essay (including this one)? What are the nuances I want in my writing? Which stories should I highlight, and how do I correlate them to the larger point I want to make?

I wrote a large chunk of All Roads Lead North in this manner. I would think about how to go about constructing the narrative while running, and as my body began to tire itself, the mind became clearer. Distances felt shorter, and writing became that much easier. Patience and perseverance – the two have to come together. A writer sits at her desk, and all too often pages remain blank. But you have to remain calm. You have to give your writing the time it demands. And you have to persist with it. You have to keep writing, until you eventually discover your ‘voice’, best described as a writing style particular to you, but encompassing everything that you’d like your writing to reflect. This is a journey you have to undertake by yourself for the most part, a Kailash kora you have to do alone.

***

Japanese novelist and marathon runner Haruki Murakami has written, “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” A lot of nonfiction writing is indeed arduous: poring over sources and references, transcribing interviews, and creating a narrative to reel in readers. But as with running, where the first kilometer is usually the hardest, with nonfiction writing too, it gets better. The aches will come, without doubt. The trick lies in not letting it get to you, to be patient, to stay on track. Let the curiosity that first brought you to the track push you forward.

For young writers, I can think of no better advice than to read widely. Read beyond your areas of interest, read every newspaper and magazine you can get. Read authors from across the world (translation is one of humanity’s rare gifts). If you read in multiple languages, nothing better than that. Read the classics to know what made them so, and read contemporary authors to know how the art of storytelling has changed. Pay attention to how characters interact, the pace of the story, the way an author uses her words. Compare writing styles between genres. And while reviews are a great way to stay updated about new books, few experiences can top spending a few hours in a bookstore, browsing through its shelves, and discovering something you’d love to read.

At the same time, never put your heroes on a pedestal. There’s no better example I can give here than that of VS Naipaul: Nobel laureate, an exquisite writer of prose, yet a despicable human being with a history of violence against the women in his life, a colonial romantic, and a right-wing Hindutva enabler. This should be a mantra not just for writing, but for life in general.

Do not fall in love with your first draft. You will probably have to mutilate it before you arrive at something you can send out to the world. Do not be so attached to your words that you refuse to see the rubbish the first draft often is. Instead, see the first draft as the first step, a foundation to the home you want to build. As Manjushree Thapa wrote in this column earlier, “Revision is what breathes ‘prana’, or breath, into my stories, animating them fully.”

This might sound like a cliche, but writing, first and foremost, is driven by passion. Write because you want to, and not with illusions of fame or glory. Writing is a tough profession, and monetarily, among the worst. As a new author, you have a better chance of surviving a shark attack than your book appearing on the New York Times bestseller list. And unless you have a trust fund parked away somewhere offshore, do not quit your job because you’ve decided to become a writer. When that desperate urge to put words down on paper comes to you, make time for it. Writing at its heart is a lonely profession; the wine parties come much later. When you are at your desk, nothing should come between you and your word processor.

Apropos the preceding point, some writers like to stick to a daily schedule (for example, fantasy writer Ursula Le Guin). Some write in bursts; when inspiration strikes them, they do not stop. Because there isn’t one single method to write, you have to find a schedule that works best for you. Personally speaking, I prefer deadlines for shorter pieces, but I also followed a rule while writing the book: come rain or shine, I sat at my desk for the first half of the day. If the words didn’t come to me on a particular day, I’d start editing what I had already written.

Finally, learn to see the world beyond your silo. Travel is said to be a great teacher, and my book would have been very different (and perhaps even bland) had I not gone to the Himalayan borderlands. But even if you don’t get to travel, attempt to understand why the world is what it is. Go beyond the trappings of your privileges. There are stories everywhere, and how you tell them is up to you. That is a great responsibility to bear. Do it wisely.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week, reporter and writer Janak Raj Sapkota writes about how his experimentation with colors and his habit of keeping a journal have helped his writing.

Books

Features

10 min read

Except for a few, most Nepali authors are compelled to pursue writing on the side while they work other jobs to make ends meet. But why is it so difficult to earn a living through writing?

Writing journeys

6 min read

Introducing ‘Writing journeys’, a new series curated and edited by Tom Robertson where Nepali writers reflect on their non-fiction writing.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week, our contributors pick their favorite lines and pieces of advice from other Writing Journeys.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Journalist Sonia Awale details how she got into science writing and journalism, and provides tips to budding writers in this week’s Writing Journey.

Books

5 min read

Set during the heart of the Gorkhaland Movement, the novella ‘Song of the Soil’ exhibits how revolutions are born in the minds of a few but built on the backs of thousands.

Writing journeys

21 min read

This week, Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson provides templates for his favorite sentences – with examples from Nepali writers.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson is back to identify eight common mistakes and provide Tom’s Twelve Tips on writing better sentences.