Perspectives

6 MIN READ

Candidates for the local level elections are advertising more and more on social media, especially Facebook, presenting the Election Commission with new problems it must account for.

On May 3, a generic advertisement appeared on Facebook, reading in Nepali, “Spend less on election campaigns — create your identity via digital medium where you can earn support and respect”. Byapan, an advertising agency based in Harion, Sarlahi, was inviting election candidates to switch to digital campaigning over traditional mediums and seek its services. This was a sponsored advertisement, meaning that it was paid for by the creator and boosted to reach thousands. A similar advertisement had been first posted on March 8 and was reactivated just 10 days before the local elections.

While a few candidates might have used the services of agencies like Byapan, others prefer to do their own digital campaigning. Mayoral candidates from across the country have been advertising on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, showcasing the growing reach of social media in the country.

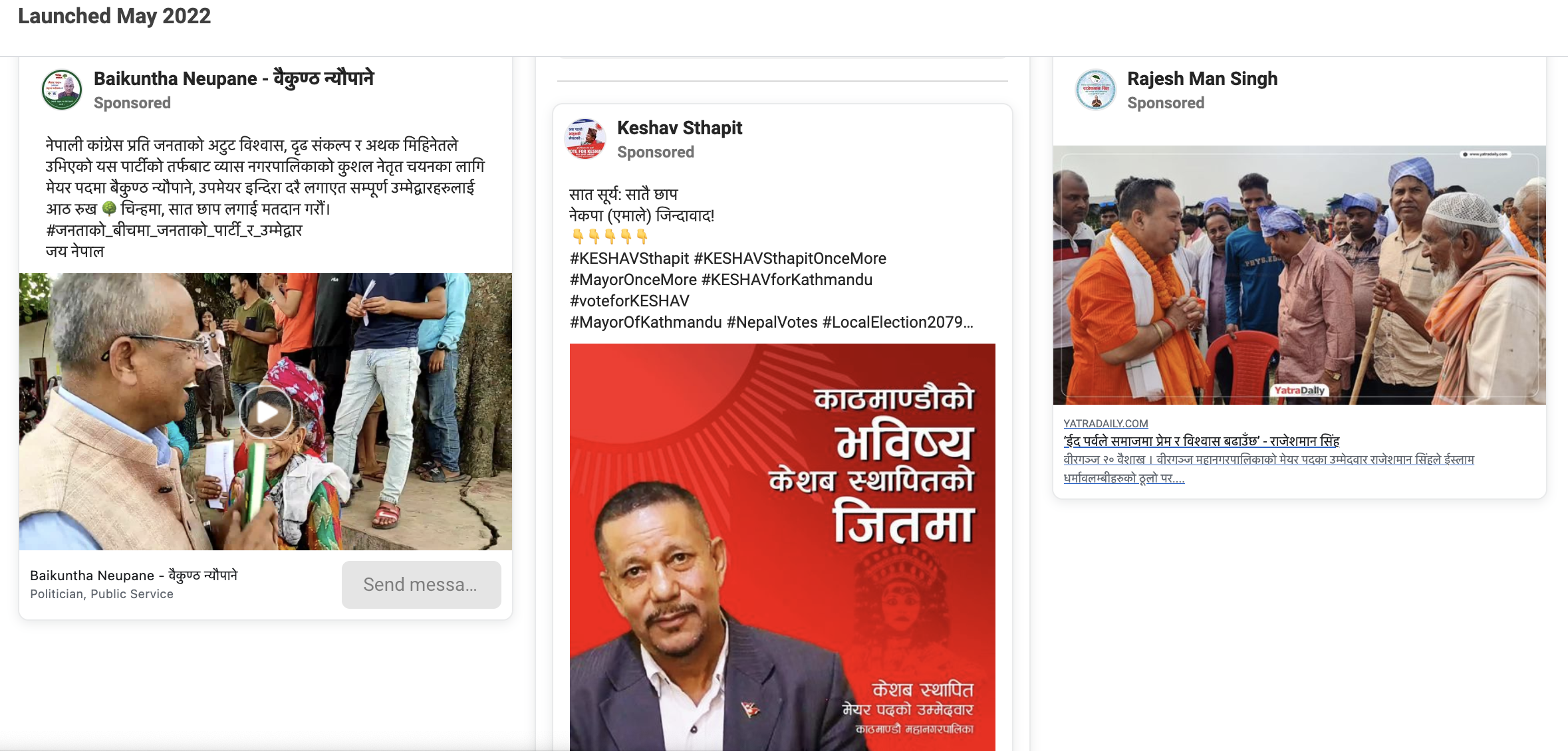

Hundreds of sponsored advertisements pop up on the Facebook Ad Library when keywords like ‘निर्वाचन’, ‘चुनाब’, ‘मेयर’ are looked up. The keyword ‘मेयर’ alone lists more than 330 sponsored advertisements for candidates, both independent and from political parties.

Until mid-April, only a few candidates had posted sponsored advertisements on Facebook and its sister platforms like Messenger and Instagram, but as the elections neared, many more have chosen social media, primarily Facebook, to reach voters with paid advertisements. Facebook is the most widely used social media in Nepal, with a reported 14.5 million users, or roughly 46 percent of Nepal’s population, compared to 13.2 million Messenger users, 2 million Instagram users, and 417,900 Twitter users. So a well-targeted ad on Facebook has the potential to reach millions of users without much effort or money spent. For less than $100, ads can reach between 60,000 to 70,000 Facebook users. For over $100, advertisers can reach 400,000 to 500,000 users in a single day.

As the election date approaches, mayoral candidates from across the country have only intensified their social media campaigns, posting photos, manifestos, commitments, and interviews, and boosting them by paying money to reach millions. Earlier last month, the Facebook Ad Library listed less than a dozen candidates who were paying for sponsored advertisements, but this month (May), the library lists hundreds of paid advertisements from candidates.

While social media campaigning can be very effective in reaching a large number of people in a short span of time, there are numerous problems that come with it. For one, has the Election Commission been keeping track of spending by political parties and their candidates on these platforms? The commission has set limits for spending on electronic marketing and advertising but keeping track of all advertisements and the amount spent is nearly impossible to calculate. Candidates with access to foreign currency already have an edge over other candidates without these means. This already makes the election campaign unfair.

In order to ensure transparency, it is also important to know who is paying for these advertisements and how much has been spent by each candidate or party. Many of these advertisements could be surrogate or ‘ghost’ advertisements, where the advertisers keep their identity hidden. This was a significant issue during the Indian elections earlier this year where these ‘ghost’ advertisers hid their connections to the Bharatiya Janata Party while paying for advertisements and boosts on Facebook.

It is likely that individuals who live abroad, have access to foreign currency credit cards and are cronies of the candidates or parties, or people with access to dollar cards, or PR firms like Byapan are helping with social media promotions. The Election Commission should thus appeal to candidates to reveal their digital spending and abide by the code of conduct.

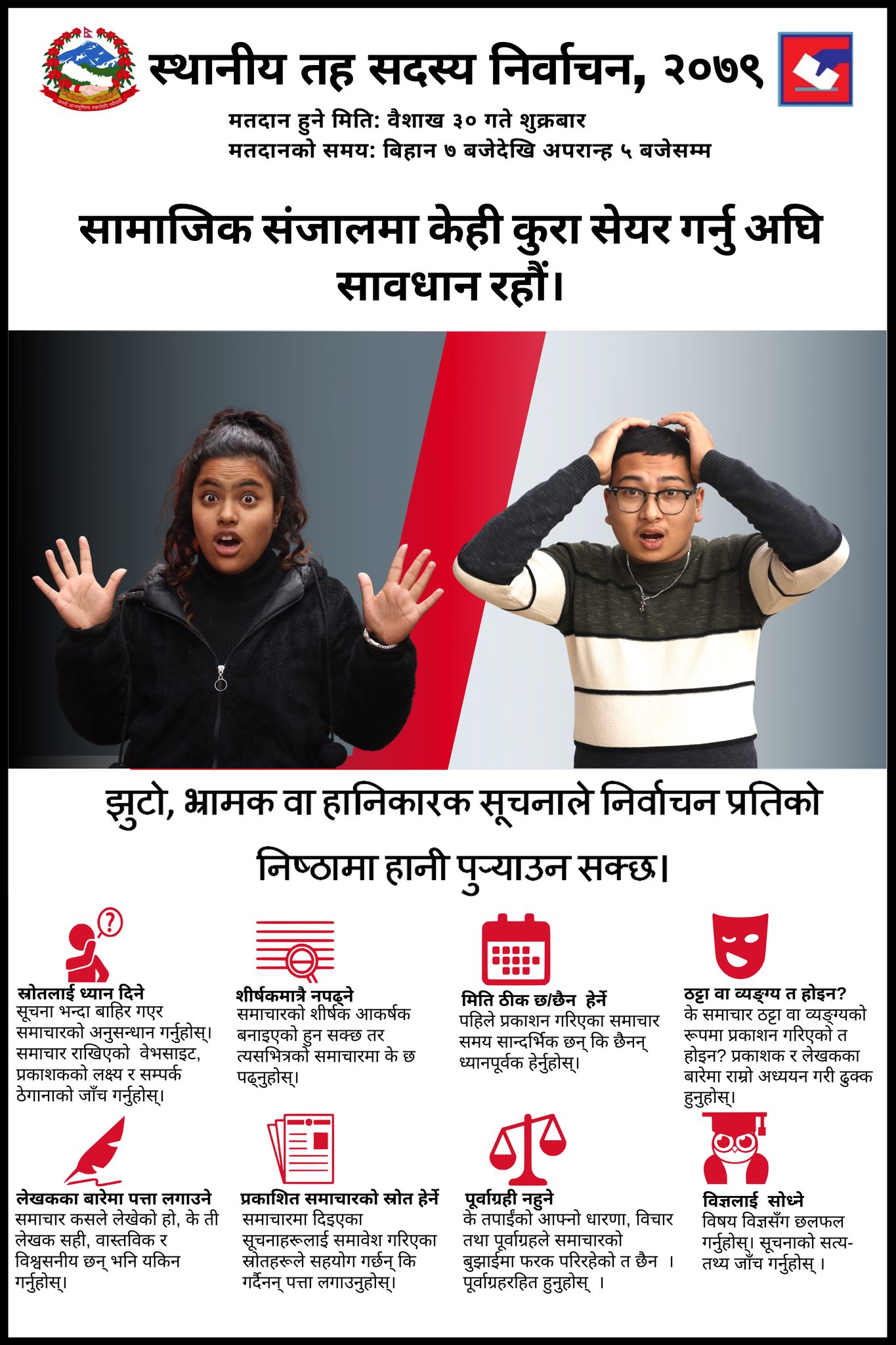

Then, there are also concerns about misinformation, disinformation, and fabrication regarding rival candidates and parties. Such misinformation can spread very quickly due to the nature of the internet. As Facebook allows targeted advertisements, misinformation can be aimed at certain communities or geographical areas. By the time that the Election Commission takes action or fact checks are issued, it can often be too late.

Another pertinent issue is that most of the advertisements are in the Nepali language, which Facebook will have a difficult time censoring for hate speech, political smears, or harassment.

The Election Commission has emphasized objectionable content in its code of conduct, prohibiting the dissemination of “misinformation on social media platforms”, “fake accounts and websites”, and “defaming content”. It has also asked and pledged the candidates to “use social media in a dignified and fair manner adhering to moral principles”. This general appeal should have been elaborated on, especially regarding what constitutes objectionable content. Furthermore, the code of conduct is ambiguous on social media and digital technology.

While this code of conduct works in theory, it lacks a pragmatic approach regarding how social media functions. Merely giving out a set of rules does not ensure that they will be followed; experts and digital observers need to be deployed to oversee such matters. The Election Commission could have set an explicit cap on social media advertisements, urging each candidate to present their advertisements together with a receipt of their spending.

These advertisements will also likely continue to run during the ‘silence period’ (48 hours before voting) and could have widespread impacts. The commission must therefore monitor social media carefully and ask candidates to deactivate all their social media advertisements during the silence period.

In comparison to traditional media, social media, especially Facebook, is virtually unregulated. On newspapers, television, or radio, editors and publishers can refuse to run advertisements if they are targeted against certain communities or consist of misinformation. Facebook, however, does not do this, especially for content that is not in English.

It is, therefore, necessary for the Election Commission to systematically monitor social media. It should be able to warn a candidate if they are breaching the code of conduct online. In order to do so, the commission could also assign a cohort of fact-checkers and digital media analysts as election observers. While it might be entirely impossible to monitor everything, such an initiative can set a good benchmark for the upcoming federal and provincial elections later this year.

Samik Kharel Samik Kharel writes and researches digital technology, internet culture, access, and equality.

Features

5 min read

Noodle, Nepal’s first digital music marketplace, is looking to provide musicians with an equitable income and fans with an avenue to support the artists they love.

Features

9 min read

What to expect with regards to local politics, American aid, immigration to the US, and the battle against climate change

Explainers

9 min read

Fact-checking viral video clip reading “Students in Butwal stage huge demonstration against India claiming Kalapani and Lipulekh is ours”.

Features

13 min read

Narendra Modi and the BJP’s focus on Hindutva and capturing state power have engendered the current health crisis in India.

The Wire

News

7 min read

Seventeen years after emancipation, many ex-kamaiyas prepare to vote in local elections for the first time

Perspectives

10 min read

As it struggles to contain the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, Nepal also faces an uphill battle with technology regulation.

Explainers

9 min read

Here’s a handy list of things to keep in mind, especially for first-time voters, while voting in the 2022 local election on Friday, May 13.

Features

5 min read

The ruling party’s top leaders have finally come to a truce, but the peace probably won’t last