Features

9 MIN READ

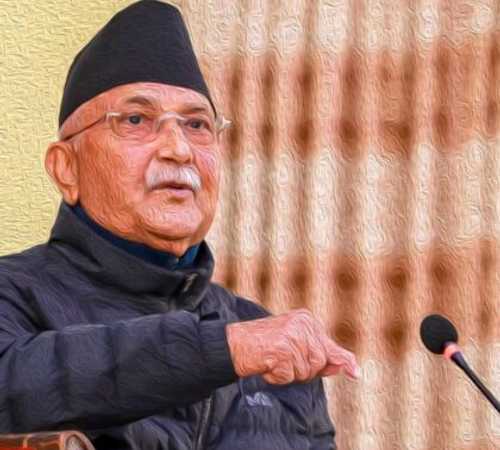

The formation of a Cyber Sena to defend Prime Minister Oli’s interests raises the spectre of censorship, trolling, and harassment.

On August 28, 2020, a new Facebook group, named the Nepal Communist Party, was created. The group initially saw little activity but on January 7, it underwent a change in its name and its ‘about’ page. Renamed to NCP Cyber Sena, the group began to see a steady influx of members, currently at over 21,500, with over 1,700 joining in the past week alone. The group has been most active in the last month -- ever since Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli dissolved the House of Representatives -- with 3,000 new posts, mostly pro-Oli news and views. The new ‘about’ page states that its goal is to “bring together all supporters of the Nepal Communist Party to make the party stronger on social media”.

Another similar group, Comrade Oli's Cyber Sena, created about 8 months ago, has more than 76,000 members. This group is private and requires any petitioner to send 500 invites before they are allowed to join

Believed to be the brainchild of Nepal Communist Party lawmaker and Oli confidante Mahesh Basnet, the Cyber Sena is the party’s most visible foray into the world of social media “warfare”. Basnet, on January 5, announced the formation of Cyber Sena (cyber army) units in each district and urged party cadres to involve themselves. One post on the public Facebook group encourages members to send out mass invites, with membership being granted upon the sending of 299 invites, a monthly ‘fee’ of 199 invites, and an annual ‘fee’ of 1,200 invites, with more than 4,000 invites granting a nomination to the ‘operating committee’.

As social media gains increasing currency, even in developing nations like Nepal, political entities across the world are now creating separate bureaus and organisations dedicated to promoting them on the internet while also policing posts that counter their narratives. Among the most notorious of these bureaus has been the Indian Bharatiya Janata Party’s ‘IT cell’, which has been accused of trolling, harassment, and spreading misinformation. China, which has among the most draconian cyberspaces in the world, has long policed the digital activity of its citizens, mobilising hundreds of thousands who trawl the web and censor any criticism of the Chinese Communist Party, especially President Xi Jinping.

Now, it appears the Nepal Communist Party is learning from its neighbors.

In an interview with the digital news portal OnlineKhabar, Basnet said that the Cyber Sena had been envisioned to be “the messenger of the government to disseminate true messages to the people” while counteracting the “fake news” against the party and its leaders.

“[The Cyber Sena] will control social media, register cyber crime cases, assist the state’s cyber crime bureau, and help punish those who are involved in activities like overlaying someone’s head onto another’s body,” Basnet told OnlineKhabar.

Basnet is former chief of the erstwhile UML’s Youth Force, a ‘youth wing’ created in 2008 to counter the actions of the Young Communist League (YCL), the Maoist youth wing that many observers had characterised as a “paramilitary” wing. The Youth Force under Basnet acquired a notoriety similar to that of the YCL, indulging in extortion and vigilantism, and engaging in violent clashes.

Basnet told OnlineKhabar that he sees the Cyber Sena as a logical extension of the Youth Force and the YCL.

According to Basnet, the Cyber Sena has been envisioned as a department in the National Youth Federation (Rastriya Yuva Sangh), the party’s youth wing. The Cyber Sena has already set up units in all 75 districts and is still being expanded, according to National Youth Federation Chair Ramesh Paudel.

“Behind the Cyber Sena is the simple reason that we need to increase our presence on the internet if we are to counter those forces that are targeting the government,” Paudel told The Record.

Paudel too described the Cyber Sena as an effort to increase the party's presence on social media and oppose those spreading misinformation against the party and its leaders.

Increasing mobile penetration has made social media ubiquitous. More Nepalis than ever before now have immediate access to information on their mobile phones and through their Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok accounts. Many political leaders have realised this and have taken wholeheartedly to social media, posting updates, opinions, and personal news. Baburam Bhattarai, former prime minister and leader of the Janata Samajbadi Party, has the biggest presence on Twitter, with 1.3 million followers, while other political leaders, like Gagan Thapa from the Nepali Congress and Rabindra Mishra from the Bibeksheel Sajha party, have sizeable followings and are very active on social media.

Much of the party building and political activism, however, remains offline. Most major political leaders do not maintain a social media presence, except for nominal ones, and their activities are still limited to speeches at public forums and politicking on the ground. The formation of the Cyber Sena shows that parties are now concerned with their digital image and are actively attempting to counteract content that they deem “fake” or “misinformation”. However, such an approach could pose a danger to freedom of expression while also placing the digital privacy, safety, and security of individuals at risk of trolling, harassment, and doxxing, say digital rights experts.

Santosh Sigdel, a human rights lawyer and right to information advocate, says that the Cyber Sena’s name itself is problematic.

“Words like ‘sena’ or ‘army’ shouldn’t be used in such a light manner,” said Sigdel, alluding to the fact that such names imply the fighting of a ‘digital war’. “If it is an IT unit of the party, they should have come up with a more suitable name.”

Sigdel’s views were echoed by Baburam Aryal, a lawyer specialising in information technology.

“The term ‘sena’ is directly associated with a security agency like the army, which is always of the state,” Aryal told The Record. “We have a whole set of security structures. For instance we have the police for law and order; we even have a cyber bureau and a Central Investigation Bureau. When these organisations are already investigating such crimes, a parallel organisation formed to intervene would be illegal.”

Rights activists fear that a ‘propaganda machine’ backed by the ruling party could further encourage trolling and harassment. Already, there are informal reports that the Cyber Sena is going on the offensive and tarnishing Oli’s political opponents. Speaking at a programme organised by the Achham-Kathmandu Samparka Manch on Friday, one of Oli’s chief political opponents Bhim Rawal blamed “Oli’s Cyber Sena” for spreading lies accusing him of misappropriating NCP party funds.

The Oli administration and Oli himself have grown increasingly intolerant of dissent. Oli’s December 20 dissolution of the House of Representatives has led to mass opposition from his own party, the opposition, and civil society. Four former chief justices of the Supreme Court called the dissolution unconstitutional in a joint statement, leading Oli to heap scorn upon them. Recent incidents have shown that Oli and his confidantes are in a place where they take serious offence to even the slightest criticism.

On January 3, a man was denied entry into a programme that Oli was addressing in Kathmandu simply for wearing a black face mask as black is often the colour of protest. The person was only allowed entry after replacing his black mask with a white one.

Five days later, on January 8, police in Kailali arrested seven young people for wearing t-shirts with “Where is Nirmala Pant’s rapist?” written across the back. Thirteen-year-old Pant was raped and murdered in 2018, leading to mass protests across the country. Despite the national attention the case received, the case remains unsolved.

“I was hoping that the prime minister would somehow take note of our frustration and do something about it,” Birodh Khadka, one of the seven who was arrested, told The Record.

Khadka said that he was held in police custody for five hours, citing orders from higher authorities. “I felt really bad about it as I wasn't doing anything wrong,” he said.

More recently, Bishnu Rimal, chief advisor to the prime minister, issued a veiled threat to Bibeksheel Sajha party president Rabindra Mishra for a tweet questioning the legal grounds for Oli’s dissolution of Parliament.

“Remain within your limits, Rabindra ji,” Rimal said. “Time will demand an answer from any celebrity who crosses the limits of decency.”

The crackdown on dissent may have increased in recent weeks but the Oli administration’s intolerance for criticism is not new. Ever since coming to power in 2018, Oli has shown little regard for freedom of speech as several journalists have been arrested and charged for libel and defamation under the Electronic Transaction Act (ETA), a set of laws meant to regulate digital transactions but which has been used to charge individuals with defamation.

“The ETA has become an easy weapon for those in power to target journalists, especially those working for digital media” Ram Hari Karki, a journalist with Dainikee News, told The Record. Karki, who is also a member of the Federation of Nepali Journalists, said that he was arrested for writing a story critical of Ram Bahadur Thapa.

There have been numerous cases where the Oli administration attempted to censor reporting and commentary regarding the activist doctor Govinda KC, Pant’s rape and murder, and other issues critical of the government. Even reporters from The Rising Nepal, the state-owned daily, were censured for their coverage of the Tibetan religious leader, the Dalai Lama.

The formation of the Cyber Sena is now leading other parties to consider their own cyber wings, akin to what happened in the mid-2000s with the emergence of the Young Communist League, followed by the UML’s Youth Force and a special wing of the Congress’ Tarun Dal.

There is already a Facebook page for the Cyber Sena of the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-Madhav Kumar Nepal faction of the ruling party that has over 10,000 members. The Nepali Congress too is reportedly considering the formation of such a wing.

Nepali Congress spokesperson Bishwa Prakash Sharma, however, declined to comment on the formation of the Cyber Sena.

“Leaders might say or do many things in their individual capacity but the Congress will only comment if it's their official decision,” said Sharma.

Given the Oli administration’s history of cracking down on dissent, rights activists believe that there is legitimate cause for concern if a ruling party is sanctioning a specialised wing to counter criticism online.

“A political party can have different cells, but such cells should not infringe on the citizens’ rights to expression, for instance, by tolling, harassment, abuse, and stalking,” said Aryal, the lawyer. “We have to look at the intention of this Sena. If its intent is to use the support of the state mechanism to control public space, the Cyber Sena will be a serious threat to democracy and civil liberties.

Corrigendum: This article has been updated with a reference to a bigger, private Facebook group. Earlier references to Facebook 'pages' have now been corrected to Facebook 'groups'.

Features

5 min read

As no formal orders have been placed and no agreements drawn up, even the Health Minister is looking to the gods.

Opinions

6 min read

We don’t understand how China actually views Nepal-India relations

News

8 min read

Fear and uncertainty loom over Afghanistan with the Taliban overrunning the country in a matter of days. Trapped in the chaos are thousands of Nepalis.

Explainers

3 min read

The momentum given by Dr KC can be a good point of departure for the judiciary to reform itself and become more pro-people in its approach and outlook.

Longreads

16 min read

Despite conservative attitudes forcing women indoors, Nepali women in the early 20th century often broke convention and took to the streets on their bicycles.

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Explainers

Perspectives

5 min read

Public quarantine facilities are becoming time-bombs; it’s time to rely on home quarantine

Perspectives

5 min read

Despite constitutional provisions, inaction on supporting laws has meant that individuals are routinely denied citizenship through their mothers.