The Wire

Features

Photo Essays

13 MIN READ

A photo essay on the Rasuwagadhi road and why landslides are cutting it more often

The above photograph [by Dawa Pemba] shows soldiers of the Nepal Army working to clear a serious blockage on the Pasang Lhamu highway, just a few hundred metres short of the frontier with China.

Nothing that follows is intended to be a criticism of the sustained efforts of the soldiers to reopen this strategic highway, and particularly the long section from Dhunche to the border at Rasuwagadhi. Indeed, the essay will be more slanted to highlighting the complex challenge they face. I know how governments can pressure armies to deliver results quickly at whatever the cost. The can-do spirit is drilled into soldiers from the earliest day of their service. “We can do it” is the instinctive reaction when presented with any challenge. Put bluntly, a downside of this spirit is that there is often a temptation to charge in without a making a proper plan. Doing so on the battlefield, when confronted by a real enemy, can lead to unanticipated outcomes, as it can when dealing with the harsh reality of Himalayan geology.

It is worth noting at the outset that meteorological data shows that monsoon rainfall across India has been below average, except in Kerala. By implication, though it may not have seemed like it in different areas, this will be the same pattern in Nepal. Why, therefore, has the Rasuwagadhi road been hit by a higher number of major landslides? Can it simply be attributed to more concentrated rain in the general area, or are other factors at work?

Geology of the area

The geology of the area through which this road runs is an important factor in any analysis. The area is very close to the Main Central Thrust [MCT] of the Himalaya. This is the weak junction where the Indian plate slid under the Asian plate causing the Indian plate to shatter and crush. To quote one report, ‘it is one of the most tectonically significant structures in the Himalayan region. Detailed geologic mapping and structural analysis of the MCT in the Langtang National Park region of central Nepal reveals that this segment of the fault zone experienced multiple episodes of south-directed movement, under both brittle and ductile conditions, during the Tertiary period’ (MacFarlane et al. 1992).

In plain man’s speak, the road traverses one of the most landslide prone areas of the Himalaya. Road repair and road building, and the continual vibration of the land caused by heavy traffic movement, as well as monsoon rainfall, add to the general instability of the soil in the area. A new road to Syabrubesi is currently being built on the opposite side of the valley to the current road. It should be open in March 2019 but early indications are that it is also going to be landslide-prone. To reach the frontier, all vehicles must still travel on the Chinese-built road, up the steep-sided valley from Syabrubesi to Rasuwagadhi.

Cause of the immediate crisis

On July 26, 2018, a major landslide at Timure, just 4 kms from the border, cut the road and killed nine people and buried several buildings. The road was opened two days later but the next day all cross-border traffic was halted after rain-triggered floods damaged a bridge on the road, just 1km from the border. On July 30, 2018, an article in the Kathmandu Post [“Timure bridge to be repaired urgently”] gave this detail on the damage:

“According to Deputy Director of the Department of Roads, General Mukti Gautam, floods have severely impacted the base pillar, the reason why the bridge is out of service. The department has taken measures to make it functional temporarily by inducting big boulders to support the base. Works for permanent reinforcement will take at least two months to begin, according to Gautam. “Water level needs to be low for us to begin permanent maintenance work,” he said, adding that this would happen only after a couple of months.

More than 300 containers and hundreds of light vehicles have been stranded due to the halt in vehicular movement, authorities said. According to the Department of Customs, the government is losing revenue worth around Rs10 million daily as overland cargo movement between the two nations has come to a standstill.”

On 28 July there were reports of numerous landslides cutting the road, with indications that clearing three of the obstructions in particular was going to present a major challenge.

Within a very short time the Nepal Army was deputed to clear the road as quickly as possible and there were immediate indications that large amounts of explosives were to be used.

Historical context

From time immemorial, pilgrims, traders, artisans, and religious teachers going to Lhasa from Kathmandu had to decide between two main routes. One roughly followed the line of the present road to Kodari, crossed the border where Friendship Bridge is built and followed a steep trail to Kuti (Tib. Nyalam). Loads were carried by porters up to this point but pack animals were used for the rest of the journey. The alternative route went north on the route that vehicles now use to get trekkers through Betrawati and Dhunche to Syabrubesi. From there it was a twenty-kilometre trail following the Bhote kosi to cross the border at Rasuwagadhi. It was a further twenty kilometres, following the river trail, to reach Kyirong in Tibet.

In 1961, King Mahendra gave his approval to a Chinese proposal to build a road to connect Lhasa to Kathmandu. The survey teams did their work in early 1962 and proposed using either of the two historic routes but with a strong preference for the Rasuwagadhi route as it was shorter and traversed easier terrain. Possibly hoping to postpone the construction for as long as possible, Mahendra insisted on the Kodari route. Within a remarkably short time, work started and the road was completed in 1966. [For more details see my article, “All change at Rasuwa Gadhi”]

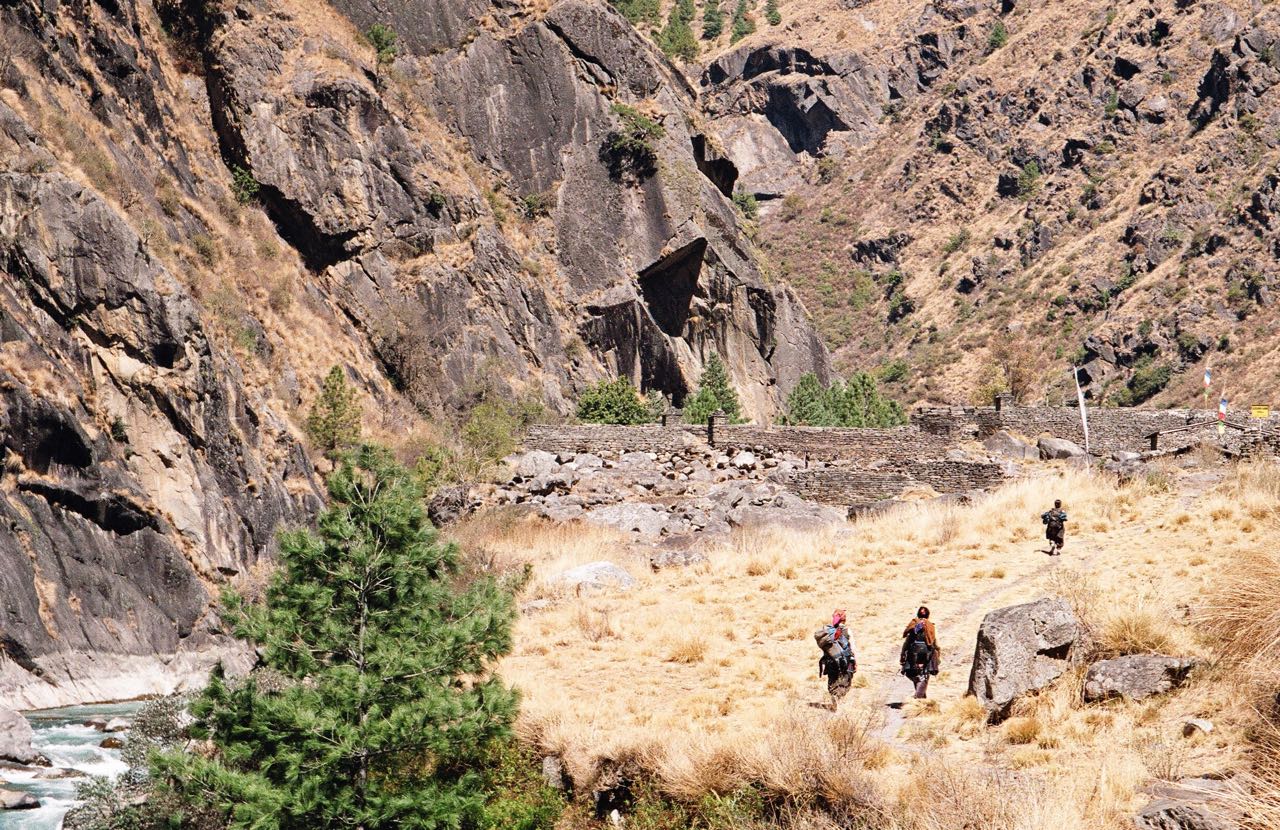

I first visited Rasuwagadhi in March 2006. Tilman had visited the place in 1949 and wrote about the journey in his inimitable style. [Tilman, H.W. 1952. Nepal Himalaya: 52-54] On my visit I found that apart from a new footbridge, a two-storey building on the Tibet side and two small huts on the Nepal side, very little had changed since Tilman’s day. As these photos show, it was delightfully tranquil.

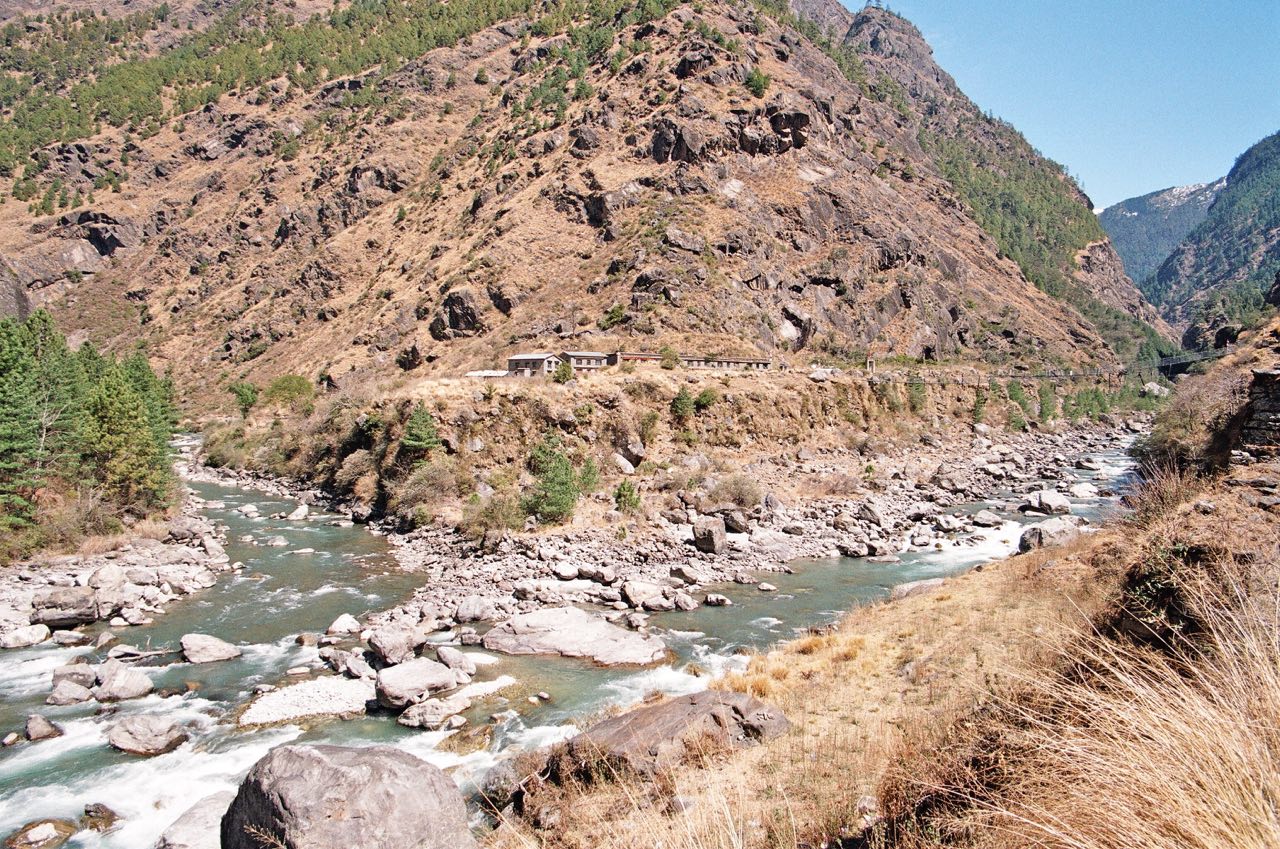

When I returned To Rasuwagadhi in March 2013, I travelled on an impressive new road from Syabrubesi that had recently been built entirely with Chinese labour and equipment. It was not yet black topped, but the strong foundations were in place to make that a straightforward task. The nine concrete bridges are clearly built to carry the heaviest loads and the safety barriers stood out as unusual compared with other roads in Nepal where such considerations are given a low priority.

The last of nine impressive bridges on the new 20kms road from Syabrubesi to Rasuwagadhi. This one built just beyond the hamlet of Ghatte Khola, 1km from the border. This is the bridge that suffered the severe damage to one of its base pillars.

A closer view of the last 500 metre stretch to the border. The essay will later concentrate on the work being done by the soldiers in the lead photo above which is around the area of the prominent black rock face. It is worth registering that this is how it looked before this section of the road was badly hit by the earthquake.

The river junction in March 2013. Behind the temporary military-style bridge, which was used to transport men and machinery into Nepal to build the road, are the concrete supports for the new fly-over bridge.

On 1 Dec 2014, the Sino-Nepal border at Rasuwagadhi was officially opened for commercial business with appropriate ceremony.

Five months after opening, the area was hit by the 7.8-magnitude earthquake of April 25, 2015. The large and imposing buildings on the Chinese side survived largely unscathed. The bridge suffered significant damage but a temporary repair enabled traffic to start moving across the border again five months later. The small and mainly temporary buildings on the Nepali side were completely buried under deep rubble caused by a large landslide. An estimated 35 Nepali and Chinese workers lost their lives. Roads approaching the crossing from both sides were also badly damaged.

These dramatic photos by Prasiit Sthapit convey the extent of the damage caused on the Nepal side of the bridge, mainly around the area where the NA soldiers are shown working in the photo at the top of this essay. They also show how rapidly China deployed a large force of the Road Repair and Rescue detachment of the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force. They did impressive work to start the process of restoring the road for use even though they were ordered to leave before they could finish the work because of an arbitrarily imposed “Nepal government’s deadline’. See this article, “Chinese rescuers return from Rasuwa as deadline expire” in the Kathmandu Post, dated May 24, 2015.

Obviously, this extensive damage left the slopes everywhere, including those down to the river, in a very fragile state.

Just four weeks ago, before news of the recent monsoon damage started to emerge, The Record published an article, “All rubble on the road to China”, which highlighted in graphic detail the slow progress being made to repair the earthquake damage on this road despite its strategic importance. This short extract conveys the sense perfectly, “Rasuwagadhi offers a stark picture of the difference between reality on the ground and rhetoric of successive governments, including that of the current Prime Minister KP Oli, who has promised greater connectivity with China for years. Despite being touted as a new trade route and a potential rail route connecting Nepal with China, construction of roads and other infrastructure on the Nepali side of the border is happening at a snail’s pace.”

The article included the above photo by Prasiit Sthapit. It is the last record we have of the state of the road at this point before the monsoon damage necessitated the deployment of the NA to the position shown in the lead photo of this essay.

For a strategic road, information on repair work in the mainstream media has been scarce. Fortunately, social media in the form of Facebook has filled the void and I am grateful to those named for posting the public posts that have enabled me to complete this essay.

This video clip from Ganesh Kumar Lama posted on 8 August before the deployment of the NA gives a graphic impression on the nature and extent of the damage done to the road just a few hundred metres from the border.

These images from the video clip indicate that the monsoon rain has caused a large part of the fragile river slope to slide into the river, thereby narrowing the road and making it dangerous for vehicles to use.

This video clip was posted on 5 September by Dawa Pemba after the NA had done some blasting and were clearly intent on doing more.

This image, taken from the clip, coupled with the images above taken before the NA started work, provide a reasonable means of assessing the outcome of the initial blasting.

The first impression is that the blasting has made an already bad situation worse. The newly created overhang is clearly dangerous, and the new section of ‘road’ is even narrower than before the blasting. In short, what was gained by the blasting was more than lost by the shock waves from the blast causing more of the steep riverbank to collapse into the river.

I discussed this with a friend who is a geologist. He made the same point in a more technical way. On the rock-slope side the earthquake has left an unstable rock mass that is prone to failure. Rather than fixing it properly, just blasting back is irrational. On the road-bench they have an unstable slope that is failing anyway. It seems that blasting is making that less stable.

No doubt a way will be found to get vehicles through to the frontier but here and elsewhere achieving this by simply blasting away by using high explosives without a coherent overall plan to fix the route will yield only temporary respite. Fragile slopes in a highly unstable terrain, made more so by the heavy earthquake damage, are being made more fragile. The continual vibration of the land caused by heavy traffic movement, as well as monsoon rainfall, add to the general instability of the slopes. An increasing number of landslides in the future are a certainty.

As I was drafting this on Wednesday, 12 September, a Facebook post gave a link to a story in Sailung Online which carried a story under the above photo giving news of a further major landslide on the road to Rasuwagaddhi.

A translation of the short text gives a familiar story:

“The landslide on Monday, 6pm has shut down transport in the Dhunche Rasuwagadhi section of the road.

A landslide has fallen on 40km of road near the permanent bridge on the Trishuli river. The district police chief Omprakash Wagle said that human movement is not possible at the current condition. Keeping safety in mind, movement at night has been stopped.

The road had opened on September 3, and had been halted within a week. More than 400 containers on their way to Kathmandu after passing through the customs are stuck at Timure.

Dozer operators from the road office, Nima Lama and Rajesh Dahal, said that it will take at least three days to open the road, and the rocks would have to be blasted.”

I passed the image above to a geologist for comment. His sobering assessment is an appropriate way to end this essay:

“The slope parallel fractures, caused by the release of stress during erosion, can be seen on the left side of the scar (directly above the people crossing the landslide). These fractures will have weakened during the earthquake. If the road then cuts into the slope the blocks defined by the fractures are free to slide. In this case they have on the right side, generating the landslide. There will be another one in due course, releasing the material on the left side.”

I am most grateful to Bob Beazley and Galen Murton for the excellent help they have given to me in composing this essay. My thanks go to all the people mentioned for posting such interesting and highly informative public Facebook posts and to Prasiit Sthapit for the use of his excellent photos.

Sam Cowan Sam Cowan is a retired British general who knows Nepal well through his British Gurkha connections and extensive trekking in the country over many years.

Features

6 min read

Despite the economy being badly hit since last year, the country’s stock market is seeing exponential growth owing to the market’s digitization and the pandemic, analysts say.

Explainers

4 min read

Misinformation and false claims about the pandemic, however, continue to spread especially through the social media.

News

6 min read

When Mayor Dillip Pratap Khand assumed office, he set out on a mission to turn Waling into one of Nepal’s first ‘smart cities’. Five years on, he has little to show.

COVID19

News

5 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Features

5 min read

Explosives used during Nepal’s armed conflict continue to take lives

Explainers

7 min read

Throughout the Covid crisis, the centre has refused to devolve power, creating more obstacles in response mechanisms than resolving them

Explainers

5 min read

Nepal’s vegetable prices are largely determined by the middlemen traders rather than by the logic of actual supply and demand

Features

5 min read

As no formal orders have been placed and no agreements drawn up, even the Health Minister is looking to the gods.