Writing journeys

12 MIN READ

Writing about disparate ideas like sustainable cities and food cultures, Prashanta Khanal has learned a lot and now, has a lot of advice to offer.

In this week’s Writing Journey, Prashanta Khanal shares a suggestion from well-known writing expert Roy Peter Clark about how to read: “Read for both form and content. Examine the machinery beneath the text.” When we enjoy an article, Clark says, we should stop reading to examine exactly what makes those words so clear and so engaging. I hope readers will do that with this wonderfully-crafted essay.

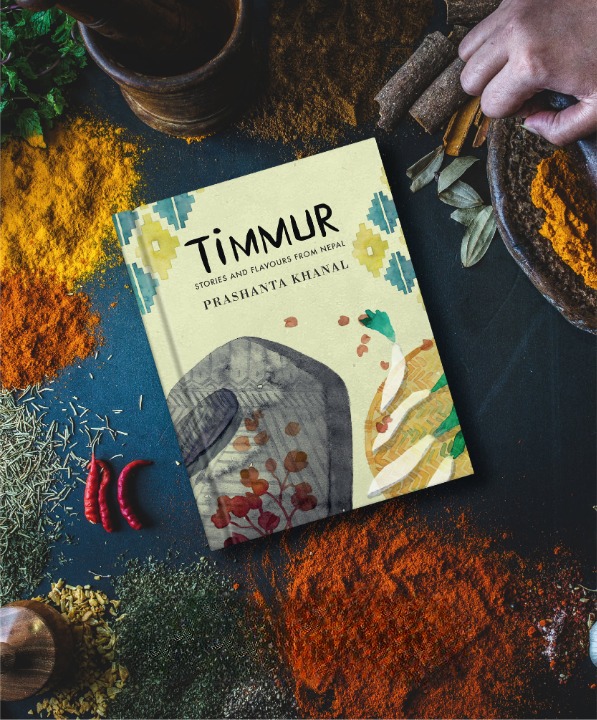

Prashanta bhai’s content is fascinating. He describes how growing up in a mixed-caste family sparked his interest in Nepal’s many food traditions. He explains how kinema – the stinky soybean dish popular in Nepal’s northeast – ignited in him a curiosity that eventually led to his innovative book, Timmur. He describes the journey of Timmur from ambitious idea to rich, beautiful reality. He offers many thoughtful reflections on his writing process.

But Prashanta’s writing is also worthy of study. If we examine “the machinery beneath the text” of this essay, as Clark suggests, what do we find? We find exquisite examples of many useful writing strategies: short, focused paragraphs; quick, smooth, clear transitions (“at first,” “in late 2011,” and “still today,”); punchy lists of three or four (almost every other paragraph); occasional super short sentences (just four-seven words, such as this powerful one: “They nurture your soul.”); short, evocative quotations; sentences with colons (Prashanta is a master); and, not least, vigorous verbs (venture, voice, shape, launch, demolish, bulldoze, discover, struggle). Best of all: no unnecessary words. Each and every word in Prashanta bhai’s essay does work; each and every word adds something valuable.

It was great fun working with Prashanta on this Writing Journey. We had the kind of idea-filled and collaborative “back and forth” with multiple drafts (four, I think) that Ujjwal Prasai discussed in last week’s excellent Writing Journey essay. We owe this week’s rich, multi-flavored essay to Prashanta’s thoughtful “cooking” and that wonderful revision process. “Often,” as Prashanta rightly observes, “the more gently and slowly you cook, the richer the flavor.”

Prashanta Khanal works on and writes about sustainable cities, urban mobility, air pollution, and climate change. His other passion is to explore Nepal’s food cultures. His first book, Timmur: Stories and Flavours from Nepal, will be out in April.

He writes occasionally for The Kathmandu Post and The Record. He wrote a series on Nepali food for The Kathmandu Post and on Kathmandu’s cycling culture for The Record. He co-authored a paper ‘Road expansion and urban highways: Consequences outweigh benefits in Kathmandu’, published in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies. He also recently published a policy brief titled “Pathways to transport decarbonization in Nepal”.

Writing Journeys appears every Wednesday on The Record. Previous editions can be found here.

***

My writing journey

I never dreamt of writing a book, definitely not a cookbook. It didn’t happen by chance. It took time.

Besides writing a few stories, essays, and poems during my school days in the 1990s, I never ventured into writing seriously until the late 2000s. A few years after I joined environmental campaigns, I started writing articles. This was writing beyond reports for my job. But the report writing created a base for my writing journey.

With environmental matters, I started writing when I got angry. I turned my rage into words. I had an urge to voice my opinions on issues I was working on: sustainable cities, urban mobility, air pollution, and climate change. I criticized short-sighted environmental thinking and government policies. I felt that a small group of people with social, economic, or political clout dominated policy discourses and development narratives. Their narrow views shaped how we live in our city, how we move, how clean the air we breathe is, and how our future will look.

In late 2011, the prime minister launched a road expansion drive in Kathmandu – demolishing houses, sidewalks, and green space – supposedly to reduce traffic congestion. The expansion wasn’t about people, but about vehicles. It would benefit the wealthy few who can afford private vehicles. I felt that bulldozing settlements to create more space for cars was unjust and inhumane. Meanwhile, many media, intellectuals, and the public alike were applauding the road expansion with no sympathy for the victims of the expansion. This led me to write ‘People over vehicles’ in The Kathmandu Post – one of the first articles I ever published – where I argued against the unplanned road expansion campaign and called for people-centric transport planning.

Getting articles printed on a national daily encouraged me to write more. It gave me a sense of purpose. I discovered that publishing an article is really an invitation to conversation. People’s responses to how the articles have changed their perspectives further fueled my writing journey.

I learned basic writing structures from studying published articles that I liked. But I didn’t write well at first. I didn’t put conscious effort into understanding the writing form. I would focus on authors’ ideas and opinions, not realizing that it wasn’t just the ideas but also the writing form that drew me into their articles.

Even today, my mind struggles to present my jumbled ideas and thoughts in a clear, concise, and coherent manner — three key aspects of a good article. I even struggled to write this ‘writing journey’.

My food writing journey began in 2013 when I created my food blog thegundruk.com, where I share my other passion: Nepali food culture and recipes. I have always enjoyed cooking and exploring new food cultures. I like digging into recipes and ingredients, their history, and their cultural significance. Growing up in a multi-cultural family with contrasting food traditions helped me to understand Nepal’s cultural diversity and ignited my curiosity to learn about new traditions.

Kinema – the Limbus’ fermented soybeans – changed my life. It changed my writing and the way I look at food. Some may find kinema’s strong smell unusual and even offensive, but the people who grew up eating it adore it. I realized that smell and taste are subjective, and that one has to train their palate to like it.

When I first discovered kinema, I realized how little I knew about Nepali ethnic cuisines. I knew more about global cuisines than my own. Nepali cuisines are narrowly defined by a handful of cuisines, a hegemony of upper caste and urban Newa food cultures. This prompted me to explore and write about the diversity of Nepali food heritages, which I set as a challenge for myself as a way of learning about Nepal’s larger cultural diversity.

Writing a cookbook was not the original plan. I started just collecting traditional ethnic recipes that were difficult to find online. Collecting recipes and writings stirred me to learn more and dig deeper, especially into Nepali food tradition and history. Eventually, the idea for a few pages of e-copy turned into a full cookbook covering 12 ethnicities and 120-plus recipes from across Nepal. The journey of writing the cookbook began with outlining potential chapters, not writing pages.

At first, I thought that writing a Nepali cookbook with stories and food history would be impossible. I wanted to make my cookbook, Timmur: Stories and Flavours from Nepal, more than just a collection of recipes. But because of sparse research and writings on Nepali cuisines, I found it challenging to gather information on food history, and to juxtapose cultural nuances between and within different ethnicities. For example, not all Tharus have exactly the same food traditions – eastern Tharu food differs slightly from that of the western Tharu.

To make sense of Nepal’s obscure food history, I used a ‘connect-the-dots’ technique to bring together scattered information. In the articles I wrote on kinema, yangben, yomari, and batuk, I explored how similar food practices exist across different Asian regions and how they might have traveled to Nepal. For example, the Limbu’s practice of eating yangben (lichen) in Nepal correlates with traditions in China’s Yunnan region. This supports some historians’ claim that the Limbu’s ancestors came to Nepal’s eastern hills from Yunnan, bringing the practice of eating lichen with them. While digging into such food stories, I realized that our histories are interconnected, and that food and culture travel and, with exchanges, thrive. I learned that we can even trace back a community’s history using food.

Food writing, however, comes with a few challenges. Food means many things to individuals and communities. Because food is so close to people’s identity – religion, culture, nationality, and memory – I realized that food writing requires careful attention and sensitivity. When I published a recipe for a traditional Newa mixed bean sprout soup kwaati together with goat meat, it outraged some people as goat meat is often associated with the ‘upper’ castes. This experience led me to write a follow-up article ‘Who owns recipes?’ explaining the context.

People often romanticize the idea of foods connecting people, but there is another side too: ‘upper’ castes and classes have used food as a tool to divide and suppress society. Food often signifies caste and class in Nepal. Caste and social class dictate who can eat what and who can eat together. A political hierarchy exists: whose food is pure and superior, and whose food isn’t.

Writing a recipe also comes with a few technical challenges. First, it requires an accurate, clear, and concise sentence structure. Second, recipe or ingredient-centered writing often demands passive sentences, which makes food write-ups tricky to make engaging. Third, there are only a limited number of words to describe food and tastes.

Writing the cookbook taught me how important it is to read books beforehand. At first, when I decided to write the cookbook, I barred myself from reading cookbooks and food stories. I worried that other people’s writing would influence my own style. But later, I started to think differently. I realized that it’s okay to be influenced. Everyone gets influenced one way or the other. Read a lot, soak up influences, but find your own way or style of writing. It’s similar to cooking.

The first draft of my cookbook read like a report, with lackluster sentences and no stories. Roy Peter Clark, in his helpful book Writing Tools: 50 Essential Strategies for Every Writer, brilliantly explains the difference between report and story: “Reports convey information. Stories create experience.”

I wanted my cookbook to create an experience – with words, pictures, and artistic design.

I decided to re-write the entire draft. If I had spent more time reading other people’s food writings or books, and paid attention to writing forms, I would have written a better book and I wouldn’t have had to expend valuable time re-writing the draft.

Clark also offered this helpful piece of advice: “Read for both form and content. Examine the machinery beneath the text.” Begin your writing by reading first.

Outlining my cookbook’s chapters before writing eased my writing process. Outlining streamlines your vision, helps you to keep track of your writing, and organizes your ideas. I also use this technique to write short articles. Outlining can be as simple as a title and subtitles, key questions, or just a one-line summary or thought, which later can be stretched into paragraphs.

I find, in many ways, that writing is like cooking. But perhaps more difficult. In both, the ingredients are important, but it is the process that defines your dish, that makes it uniquely your own. As in cooking, there are many approaches to cook up an article, but one requires basic techniques to make it flavorful. Often, the more gently and slowly you cook, the richer the flavor. Like fermentation or aging whiskey, time deepens the ideas and characters.

It took me over five years to publish my book, primarily because of a lack of discipline. But time brought benefits: it allowed me to better understand Nepal’s food cultures and their nuances. Time helped the cookbook become more full-bodied and flavorful. As writer and historian Satya Mohan Joshi told The Kathmandu Post: “Research is difficult, and a book needs its time to evolve.”

Writing and cooking are acts of creation: one creates ideas and the other creates flavors. Both nurture you: cooking nurtures your body while writing nurtures your mind. They both nurture your soul. Not only yours but also of your surroundings.

Writing is a way of expression. So is cooking. Especially in Nepali culture, we express our love and gratitude not with words, but with food. In a way, both writing and cooking are extensions of who you are, your personality.

Only lately did I learn that writing is more than expressing your opinion. As other writers in the Writing Journey series have indicated, writing is more about self-realization, self-exploration, and self-examination. Writing makes you think and question your own narrative.

When I write, I write for myself first. I wrote the cookbook primarily to enrich my own understanding of Nepali cuisines and my country. But I hope others learn from my journey.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Longreads

Features

Popular

23 min read

Boudha once had a long and rich relationship with water but with the explosion of concrete houses and paved roads, fresh water is becoming more and more scarce.

Writing journeys

6 min read

Introducing ‘Writing journeys’, a new series curated and edited by Tom Robertson where Nepali writers reflect on their non-fiction writing.

Writing journeys

14 min read

Activist and researcher Indu Tharu recalls what it was like growing up and studying during the civil war and how that experience formed her writing consciousness.

Writing journeys

11 min read

A poet, teacher, and sometime business reporter, Ramesh Shrestha details his writing journey from Bhojpur to Kathmandu to the US, and to Thailand.

Writing journeys

17 min read

As the old year comes to an end and a new one begins, we look back on a year of Writing Journeys, reflecting on the diverse stories we've read and the great advice we've received.

Interviews

11 min read

In an email interview with The Record, Nepali-Indian poet Rohan Chhetri expands on the ambitions of his poetry, his influences, and his use of the English language.

Writing journeys

7 min read

In this week’s Writing Journeys, researcher and feminist writer Kalpana Jha provides insight into how writing can be a process of discovery and analysis.

Interviews

11 min read

A 1963 interview with writer and critic Krishna Chandra Singh Pradhan