Features

8 MIN READ

The risk is most acute for residents of the Khumbu region, which hosts a majority of the country’s glaciers and has settlement areas close to retreating glaciers.

When Dig Tsho, a glacial lake located in the Langmoche valley in the Khumbu region, burst in 1985, alarm bells sounded across the world. It wasn’t because Dig Tsho was the first glacial lake that burst in Nepal — a number of glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) events had occurred in the country and across the Himalaya before. The event caused such an uproar because of the severe socio-economic impacts it wrought on communities downstream.

When the glacial lake dam collapsed, the water drained into the valley below for over four hours, wreaking havoc as it went. The outburst destroyed the nearly completed Namche Small Hydroelectric Project, some 11 km downstream, causing losses of $3 million and killing five people. The discharge was an estimated 6-10 million cubic meters of water.

“The flood itself wasn’t a big one but it showed that even small meltwater lakes can cause much destruction, especially if there are populated areas and infrastructure located nearby,” said Sharad P. Joshi, cryosphere analyst at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), a regional government body based in Kathmandu.

Today, almost 33 years after the event, the lake no longer poses a threat. But since then, a number of other GLOF events have taken place in the region. According to ICIMOD’s 2011 inventory on glacial lakes, Nepal has experienced 24 GLOF events in the recent past, several of which have caused considerable damage and loss of life. The most recent ones occured in 2015 and 2016, both of which originated in the Lhotse glacier.

With the temperature rising with each passing year and glaciers retreating and forming glacial lakes at a formidable pace, the possibility of another GLOF disaster is never too far away. Because such lakes are inherently unstable, they can be catastrophic to people and property in the valleys below them when they burst.

The threat of destruction is scarier for Khumbu, a region that hosts a majority of the country’s glacial lakes and has settlement areas close to retreating glaciers.

“Glacial thinning and retreat in the Himalaya has resulted in the formation of many new glacial lakes since the 1950s, and the number of lakes is increasing every year,” said Sudeep Thakuri, a glaciologist and dean of Mid-West University, who has conducted extensive research on glaciers and glacial lakes in the Everest region.

According to a 2016 paper co-written by Thakuri that analyzed data from 1962 to 2011, glaciers in the Everest region have been shrinking significantly, supporting the estimate that glacial lakes in the area have undergone the greatest expansion in Nepal and are thus at greater risk of bursting.

A 2017 inventory of glacial lakes across the Nepal Himalaya, also co-authored by Thakuri, cataloged a total of 1,541 glacial lakes in the country, among which 234 lie in the Dudh Koshi sub-river basin, a majority of which falls in Khumbu. Seven of these glacial lakes were assessed to be very susceptible to outbursts. Among them, Lumding is one lake that is very likely to burst. From 1987-2016, it has been expanding at a rate of 0.018 square kilometer every year. No mitigation measures have been adopted yet.

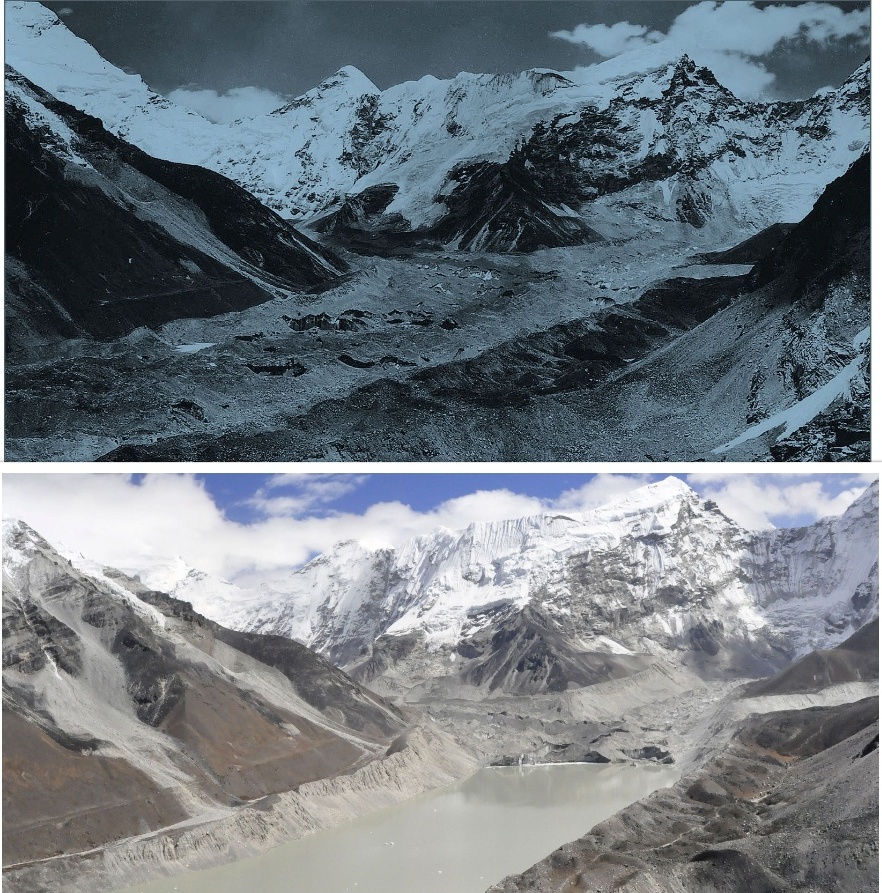

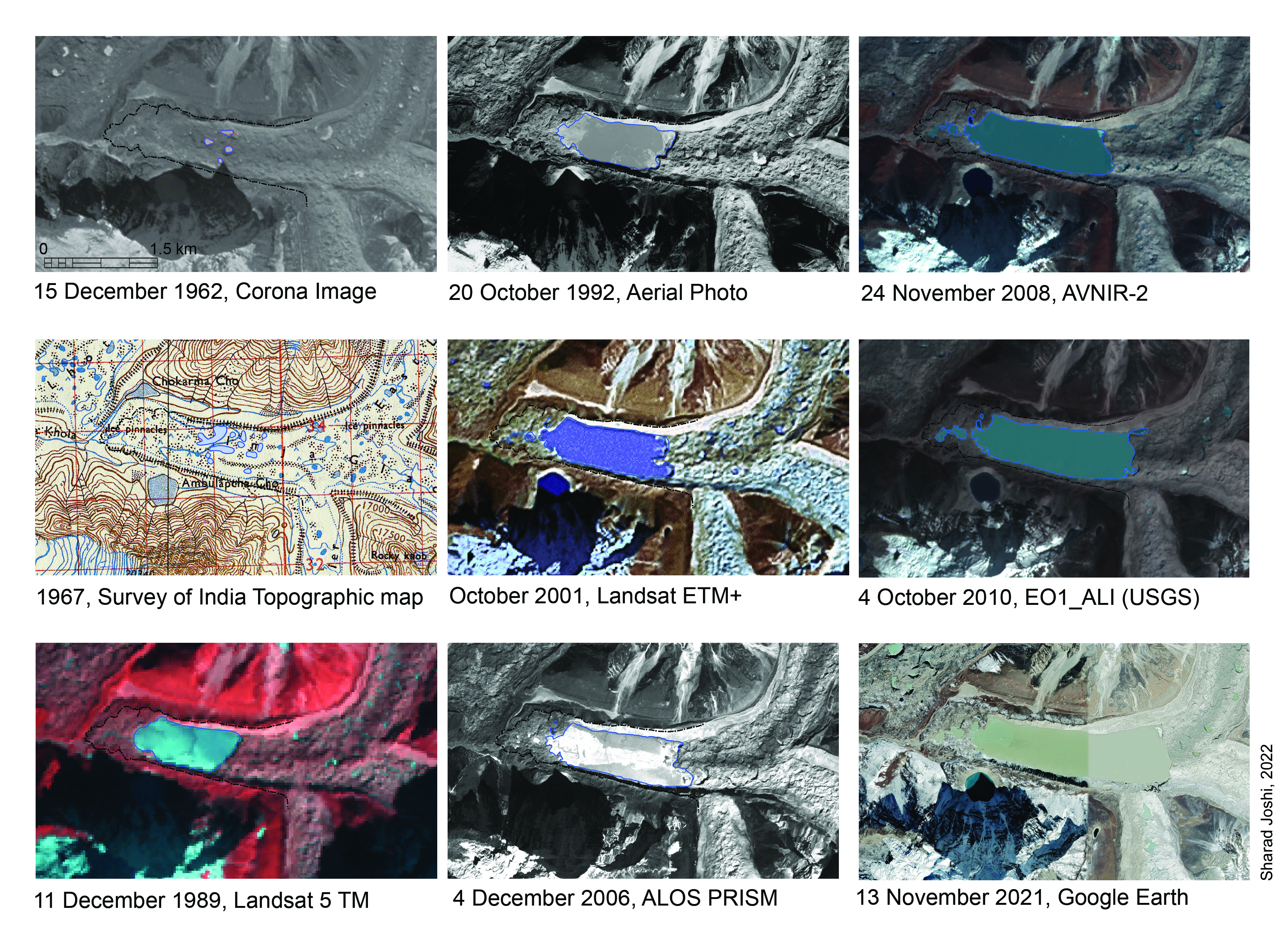

Another lake in the region that has alarmed scientists is the Imja Tsho, a glacial lake that began forming in the 1960s. Ground photographs taken in the1950s demonstrate that except for small melt ponds on the Imja glacier surface, no lake existed at that time. But by 1984, a lake of approximately 0.4 sq km had formed, according to the 2016 paper. Today, the Imja Tsho is 2.7 km long and 0.7 km wide, with numerous supraglacial ponds dotting it.

“Imja Tsho is perhaps the best example of what the warming climate is doing to the earth’s glaciers,” said Joshi. Understanding the damage the lake could wreak on downstream communities, the government of Nepal in 2016 established an early warning system in the lake and lowered the water level by 3.4 meters by constructing a drainage channel.

But the estimated exposure to potential GLOF risk to the villages of Dingboche and Phakding (8 km and 33.6 km downstream of the lake’s outlet, respectively) is still very alarming. According to ICIMOD’s assessment, the number of people likely to be affected by this potential GLOF event varies between 5,000-7,000 people. The number of people who could be directly affected through infrastructural damage and loss of goods and services is around five million.

Alongside the socio-economic damage and loss GLOFs bring about, they also cause irreversible ecological damage.

“Glacial lake outburst floods leave behind a trail of destruction: making the areas they pass through prone to landslides, triggering further destruction. They also alter the landscape of a place,” said Joshi.

Owing to the warming earth, besides the threat of glacial lakes bursting, retreating glaciers is also a lingering risk in the region. The Everest region is characterized by large debris-covered glaciers, like the 12-km-long Khumbu glacier, which is also receding at an alarming pace.

The Khumbu glacier is the highest glacier in the world and it has receded at an average of 30 meters per year in the past 20 years. Not only that, the glacier has also shrunk vertically, losing up to 50m in thickness, according to a report by Nepali Times.

“I started climbing in 1979 and over the years I have seen first-hand the changing facade of the Khumbu glacier,” said Tenzing Tashi Sherpa, 67, a retired mountain climbing leader.

The warming climate is also forming meltwater ponds as glaciers retreat.

“When I was younger, Chola Pass was covered by snow all year. But over the years, the snow cover has drastically reduced. At one point, a meltwater pond had also formed on the pass. But it eventually drained out,” said Pemba Tsering Sherpa, a resident of Khumjung. The Ngozumpa glacier, the longest debris-covered glacier in the Himalaya, is right on the trail of the pass.

And it is not just the Khumbu in the Everest region that is witnessing such changes. The risk is spread across the Himalaya. Tsho Rolpa is another large, potentially dangerous glacial lake in Nepal that has been the subject of extensive research and monitoring for decades, with the government of Nepal placing it on its priority list in 1997 and putting in place mitigation measures by 2000.

Yet, the threat of an outburst looms. The lake has been consistently expanding over the last 60 years and has now swelled to an area of 1.6 sq km. The lake is directly fed by Tarkading glacier, which has been continually retreating at a rate of 60m annually from 2009 to 2019. The flooding of this lake would be disastrous, as around 6,000 households are at risk.

And things are only looking grimmer. A report by ICIMOD, titled Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Climate Change, Sustainability and People, states that by the end of this century, the Himalaya will lose more than one-third of its ice. Adding that even that will happen only if the global average temperatures can be capped at a 1.5 degrees Celsius — a target that will most likely not be met. In addition, the Himalaya are warming between 0.3 to 0.7 degrees Celsius faster than the global average, and the loss of Himalayan ice would have devastating consequences for the communities living downstream and eventually, the entire world.

But for now, the fear of immediate threat is felt by the people living high up in these high mountains — people who have themselves contributed little to the melting of the glaciers.

“Every year, many researchers come, scientists come and do their research and leave. They tell us the Imja is about to explode and the Khumbu is melting. They scare us about our future, but give us no solutions. What can we do with that information? What can we do except continue to live here?” said Tenzing Tashi.

This story was written as a part of the 2022 edition of the Himalayan Climate Boot Camp, funded by the Spark Grant Initiative of the World Federation of Science Journalists.

Marissa Taylor Marissa Taylor is Assistant Editor of The Record. Previously, she worked for The Kathmandu Post. She mostly writes on the environment, biodiversity conservation and public health.

Perspectives

9 min read

In addition to building resilience against climate change, we must also come to terms with the trauma it leaves us with.

COVID19

News

5 min read

The Valley’s CDOs got the government’s green light to clamp strict measures on account of rising case numbers

Perspectives

Film

8 min read

This feature documentary highlights the direct and indirect costs of climate change through three unique stories across Nepal, linked by its central theme: water.

Features

6 min read

As the world heads towards the annual climate conference, Nepal needs to push for more climate financing and support to mitigate outcomes and adapt to climate change.

Features

6 min read

Here’s what you need to know about the floods and landslides wreaking havoc in districts across the country.

Photo Essays

3 min read

Aging gracefully has little to do with skincare and facelifts; aging with dignity is about honoring your age, your journey, and your being.

News

4 min read

More than 70 lives have already been lost to this past week’s rains with the toll only expected to rise.

COVID19

Perspectives

11 min read

While the state of mental health of Nepalis is largely unknown, estimates and anecdotal evidence suggest that the pandemic and climate crises have exacerbated problems.