Features

9 MIN READ

Her photographs confront the culture of silence that surrounds women

Unsmiling, staring steadily at the camera and, through it, locking eyes with the audience, commanding attention with her gaze, Bunu Dhungana looks unequivocally, unapologetically angry.

“Everything around me makes me angry these days. I sleep angry and wake up angry,” said the photographer. In her self-portraits, anger, indeed, is the predominant emotion. Her tone as she spoke about it was soft, shy, light-hearted even. She appeared demure and tentative. The person in the photographs and Bunu Dhungana the person might as well be different people.

In these self-portraits, Dhungana takes culturally charged items such as the bindi, sindur, kapaal baatne dhaago, ghumti – all of them red, all markers of a wedded woman’s identity – and toys with them using her sexually charged female body almost as a canvas. An unmistakable subversion is at play. In one portrait, red lipstick not only coats her lips, but is smeared far beyond them. In another, the ghumti strangles her, and in a third one yet, bindis dot across her entire face, covering her in a feature-less red mask. The effect is startling. What are otherwise sacred items in a married Hindu, Nepali woman’s vanity case – and are used to adorn her, to make her look beautiful, to celebrate her finally becoming whole in her communion with a man – are in Dhungana’s case disfiguring her, silencing her, mutilating her in her current state of singlehood. Glaring at us through the photographs, what is her piercing gaze trying to convey?

Although she grew up in Nepal, Dhungana spent a large part of her youth in India, studying and working there. Only upon visiting Kathmandu during the 2016 Photo Kathmandu did she find appeal in the visual movement. “I think this is one of the best times for photography in Nepal,” she said. “So I found myself asking, why am I staying in India? Why am I running away?”

“ I came to realise that I feel so restricted when I come to Nepal,” she said, revealing the invisible plight of women who actively choose singlehood as a way of life. “While you’re away, you have your own life. It’s questionable how free you are but when I’m away, I can do what I want. There’s always something in your head when you’re in Nepal. And that is how my work started, with the question – why does Nepal bother me so much?”

Her work explores this fundamental relationship between a woman and her home. But what is a home for a woman who is 36 and single? Meant to be transitioning from her father’s house to her husband’s, yet choosing to remain in the no-man’s land between being a daughter and a wife, Bunu Dhungana, a woman – and a human being – faces the daily unease that confronts her. Does she have the right to have a home if she doesn’t choose a husband? “I don’t really feel so free here,” she said of Kathmandu. For all these years, has it been Dhungana who has run away from home? Or has her home constantly rejected her?

For instance, like most Hindu upper caste households, Dhungana’s rejected her for four days straight every month for being a woman who bled. “The root of oppression for us lies in untouchability during menstruation,” Dhungana stated, commenting on the ritual of banning menstruating women and girls from touching “sacred” spaces within the Hindu home. “I still remember; I couldn’t understand it at all. Why am I being segregated like that, that I can’t even touch the carpet?”

“Somehow you grow up being unsure of yourself,” she added, implying that being reminded constantly during one’s formative years of a biological “defect” or impurity that one could never rectify can take a toll on one’s self-esteem. “In a way, even today, I have that…” her voice trailed off, sentence unfinished. Then, “I hope my work pushes me to be confident of what I’m doing.” A statement that highlights the redemptive capacity of art. “I know what I’m doing,” she asserted confidently. “But there’s this…always this…” another unfinished sentence as she searched for the right word – always this doubt? insecurity? feeling of inadequacy? – she did not say explicitly. “Where does this come from?” this time almost rhetorically.

Dhungana believes that she has never been very nimble with words. “We measure people’s intellect through how articulate they are,” she said. “But that limits the scope. Whose story do you get to hear?”

Photography is the way in which Dhungana has chosen to tell her story. She rests and relies on the visual medium and from someone who pauses and sputters as she speaks, Dhungana transforms into an entirely different force as she lets her images do the talking. I know what I’m doing. Her images corroborate this statement wholeheartedly.

Digging the menstrual blood from taboo corners of Nepali society, Dhungana spills it – along with her rage – onto pure white surfaces for the world to see. In this particular series, used pads, tampons, menstrual cups are showcased. These photographs appear straightforward, clinical – more like mugshots documenting items that have been deemed criminal in a cultural silence that surrounds them. What stories do they tell? What questions do they propel towards the audience? “There was so much shame associated with that…to buy a pad, was so embarrassing,” she recounted of her youth. “Even now, if there’s a little bit of menstrual blood showing on your clothes, how do you feel? Won’t it make you feel uncomfortable? But why?”

For Dhungana, putting up images of her menstrual blood serves the purpose of putting a mirror in front of the audience so that audience members may see, though her work, contents of their own minds.

“So this is what the point is, to show this and say, here it is. I hope it makes you feel or think something. I still remember one of my friends who said she enjoyed the work so much because she could imagine the face of her boyfriend when he would see my work. In a way, men are equally part of the conversation.”

And yet wholly absent. She remembers how her father – even as he was to her open-minded, liberal, philosophical – did not speak about menstruation. Lines were drawn, sanctions made, and patriarchy – in this regard – handed down entirely through conversations between mother and daughter.

Dhungana is most excited about young people coming and looking at the photographs and what it might offer youngsters in the way of conversations they may talk about uncomfortable topics, and return with their minds full of difficult and nuanced questions. Confrontations is also part of Photo Kathmandu’s arts and education programme and school students will attend guided tours to engage with her photographs with an educational goal.

As a photographer, Dhungana found her calling much later in life, after she had dabbled in social science research and academia, including an MPhil programme she dropped out of. She finally settled into photography, which resonates with her organically and which she admits she is addicted to. But in the beginning, she had taken this profession in a different way. In fact, she said she tried to unlearn what she had learned in her Sociology degree at university so she could be more true to her photography. “You hear people say the personal is political but I never really related to it in my life,” she confessed. It was only when she attended a workshop by Sohrab Hura – who is also exhibiting at this year’s festival – that she began to see the connection between this statement and her work. “He would keep questioning me – why are you doing photography? So I started exploring, what are the things that matter to me,” she said. Admittedly, Dhungana’s work is deeply personal, where she offers a glimpse into intimate parts of her physical and psychological being. And because her condition is so universal, in telling her very personal story, she is able to reach out to, resonate with, and represent womankind in a deeply political way.

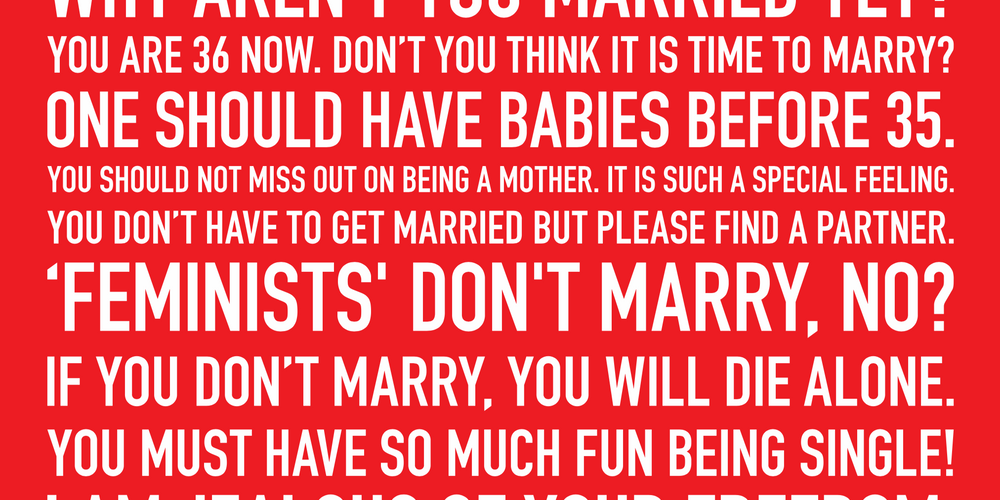

Between the personal and the political is the more murky realm of the interpersonal where Bunu tries to negotiate a space for her relationship with her parents, especially her mother. It appears as though Dhungana and her mother are on two opposite sides of a schism that cannot be bridged – with opposing values, desires, perspectives and aspirations from life. “I always see my mother looking at me and thinking, why are you like this? Why can’t you be or do as other girls in the family have done? As if there’s something missing in my life. And I keep telling her, why can’t you tell me once that I’ll probably be able to take care of myself?”

One component of Confrontations is a multimedia slideshow: portraits of mother and daughter accompanied by a voiceover of Dhungana reading out from a letter from her mother. Her mother is tender, even as she complains about how Dhungana has not been able fulfil her wishes. She writes from a vantage point where she knows her daughter will never join her. Dhungana’s voice, though steady at first, betrays her emotions as it begins to falter towards the end of the letter, brimming with tears she is trying to hold back.

While Dhungana has learned to explore life through the curving end of a question mark, her mother is preoccupied with the straight societal arrow that points to her daughter as an aberration of social norms, and to herself as a failed Nepali mother. In this interpersonal space, nothing is black and white, and both women are granted their dignity, by that strange interpersonal thing called love that emerges in all its complicatedness. That makes it possible to empathise with a perspective that one can never rationally stand behind. That makes it possible to accept even when you don’t understand. This comes across in Dhungana’s photographs with her mother.

Had she never been nudged to showcase her work, Bunu Dhungana might have hoarded all her photographs for herself. Now that she has let go and shared, she sees the value in allowing her work to be an initiator of conversations in a repressed and oppressive society. “I still couldn’t believe it when people said, oh my god, this work is so powerful,” she said, smiling.

What makes her work powerful? The power comes in her context of being a female photographer from South Asia, of being Nepali, Hindu, Brahmin – all of which trap her body, its bodily fluids, and her subjectivity in a web of the sacred and the sacrilegious – telling her own story through the visual medium. The power also comes in its universality. Because menstruation, body-image and shaming, physical and sexual violence, patriarchal domination of women are such obvious and everyday aspects of women’s realities. All Dhungana does is point her camera to these silenced parts of women’s very universal experiences. Only because of the taboos and stigmas that shroud women’s voices, her confrontation – which only about brings to the surface what has been simmering right underneath all this while – appears to cause a mental earthquake of sorts. The power also comes in how timely it is. It is a year after the downfall of Hollywood moghul Harvey Weinstein and into the global #metoo movement, and only a few months into Nepal grappling with Nirmala’s rape and murder. This week has brought a wave of allegations against Indian filmmakers and journalists where women in India have tried to speak up against sexual assault in the workplace.

The power is in how simple yet nuanced Dhungana’s efforts are. By taking seemingly innocuous parts of women’s lives – the sanitary pad being worn by a woman, for example – Dhungana is able to give a nuanced account of how patriarchy operates from that hidden space, refusing to leave, causing a rash and stinking up our consciousness.

“I try metaphors, but I am a very straightforward person in life,” she spoke of herself. “And I want to be direct. I don’t want to be subtle anymore. I’m tired of being subtle. Be subtle about something that is really killing us? Why? Why can’t I be direct?”

And so, image after image, Dhungana arrests us in steady confrontations.

Confrontations is being exhibited at Photo Kathmandu photo festival. It will be on display in Khapinchhen tole of Patan from 12th October to 16th of November.

:::

We welcome your comments. Please write to us at letters@recordnepal.com.

Features

9 min read

Her photographs confront the culture of silence that surrounds women

Culture

22 min read

“Struggle is my life; literature is my hobby— ” Shankar Lamichane. Uttam Kunwar’s 1966 interview with the eccentric essayist

The Wire

Features

11 min read

The Maoist war molded Kapileshwar Sardar, a leader unthinkable a generation ago. But he is still denied the national stage.

Perspectives

Longreads

10 min read

Remembering Fr. Stiller, who chose to dedicate his life to Nepal and to the study of Nepali history

Features

Longreads

18 min read

Nepal is pressing ahead with controversial plans to launch commercial farming of wild animals in the country, as major traditional Chinese medicine companies seek to invest.

Books

5 min read

Niranjan Kunwar’s memoir of life as a gay man is the honest account that Nepal’s literary sphere and LGBTIQ community have long needed

Writing journeys

6 min read

Introducing ‘Writing journeys’, a new series curated and edited by Tom Robertson where Nepali writers reflect on their non-fiction writing.

Books

4 min read

In her autobiography, Hisila Yami provides a complex narrative that blends her personal narratives with contemporary political happenings.