Perspectives

8 MIN READ

In the first part of a series, Tim I Gurung, writer, businessman, and former British Gurkha, details his life as Gurkha in Hong Kong.

Located just a few hours' walk to the west from Pokhara, the village of Dhampus has made quite a name for itself in recent years as a tourist destination. Before 1980 though, it was just another Gurung village in the region that relied on farming for a living. Pokhari Nasa (Pokhari village in Gurung dialect), situated atop the hill of the Dhampus ridgeline, had just over two dozen houses occupied mainly by descendants of the same couple.

The villagers were farmers and grew maize, wheat, millet, rice, and other crops as daily staples. It was also the era when each family member pitched in and shared the burden of household chores. Even children did their morning chores before and after school; there was no day off.

Apart from farming, the other primary factor that had a massive influence on the villagers was Lahure Pratha. There wasn’t a single family that didn’t have at least one member who had served in a foreign army, primarily the British Army. It was either a grandfather, an uncle, or a brother, and if not, a sister or an aunt was married to a British Gurkha. There was simply no escaping it.

The entire village lived, breathed, and dreamed as Gurkhas. Boys dreamed about becoming Gurkhas while girls aspired to marry one. Becoming a Gurkha was a tradition, a way of life, and the only option they had for a better life.

I was one of those boys.

I was 17 when I joined the British Army as a Gurkha, and it was one of the happiest days of my life. As the first son of a non-Gurkha father, the onus was on me to become a Gurkha, and I was pretty comfortable being one. Even better, I was greatly relieved for a rather personal reason.

We were three friends in high school — one was good at school, another was a star player, and the third made the team come together. We always stuck together. I woke up one day with a real problem on my hands when my two friends moved to Pokhara in preparation for the School Leaving Certificate exam. I still had one more year of study, and being alone without them in the school was almost unimaginable. As a Gurkha, I got a much-anticipated escape route, and I was genuinely relieved.

After going through the grueling selection process, I finally arrived in Hong Kong at night. The first impression that stuck for the rest of my life was the unusual brightness of the street and neon lights all over; it didn't feel like nighttime at all. After being loaded into a military bus, we went to an army depot, got our military kits issued in a big black plastic bag, and arrived at an army camp after driving for an hour or so. By the time we got introduced to our beds, stored the military kits into the wardrobe, and readied for the night, it was already very late and it didn't take very long for us to fall asleep. But the moment we closed our eyes, we were disturbed by a barrage of shrill noises and we were kicked out of bed. What we didn't realize was that the basic recruit training had already begun, Gurujis, military instructors, were barking orders non-stop, and all we could do was run, gasp, and run again.

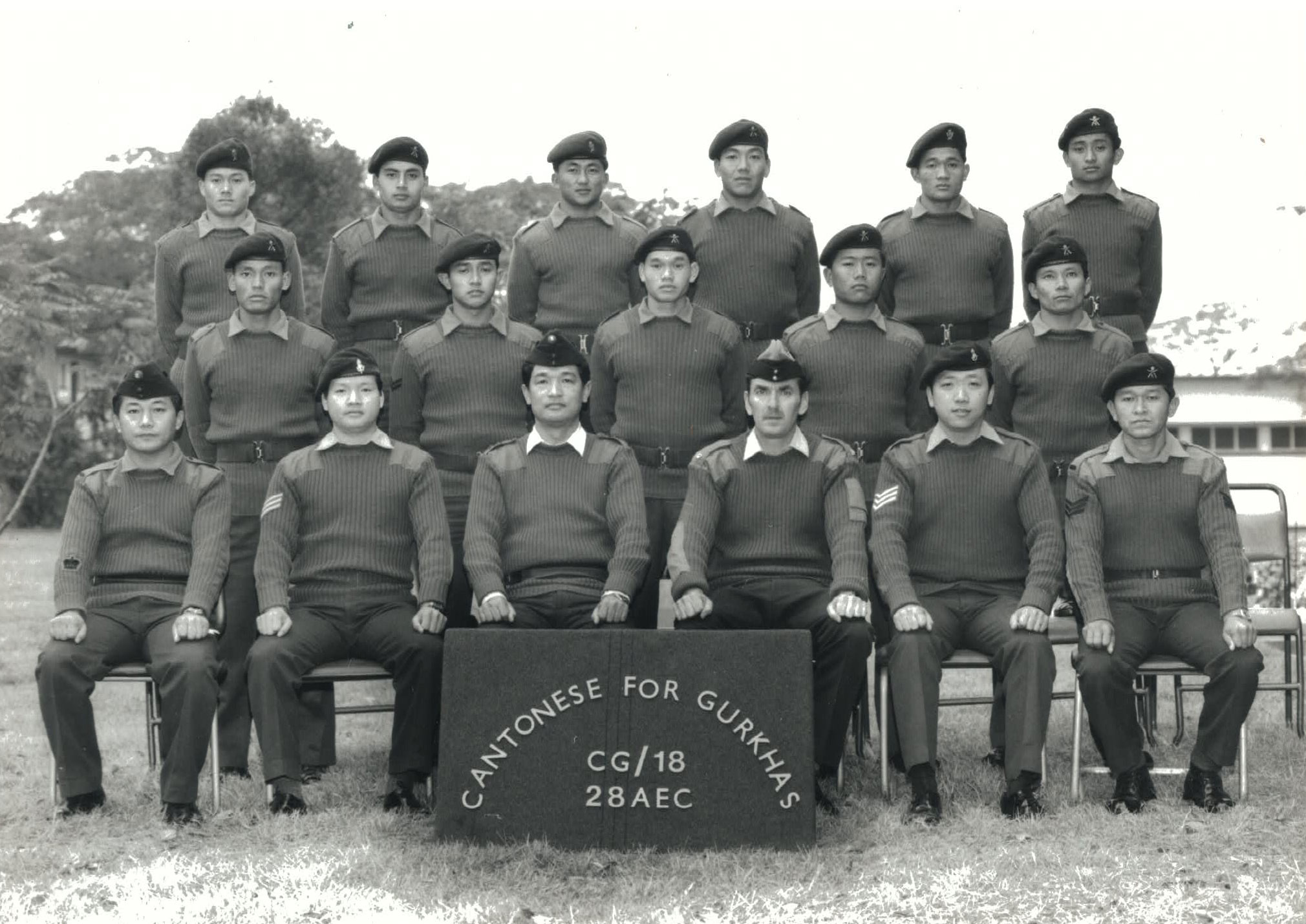

We didn't get to think or feel much for the next nine months, for we were always in a hurry and under some pressure. We learned military discipline, weapons training, jungle warfare, shooting, drilling parades, running, fitness training, swimming, first aid, map reading, and many more. Yet, the first thing I remember from my recruit training days is the smell that came out of the cookhouse. Each time, I felt like vomiting; it took a week before I could stand it.

After completing the basic training, we were assigned to our respective regiments and deployed to the China-Hong Kong border the same night. This was 1980, the year when the British enlisted three batches of Gurkhas as opposed to the usual one. The risk of Hong Kong being overrun by an influx of Chinese immigrants was great and the British needed more Gurkhas to protect the borders and safeguard their interests in Hong Kong.

Border duty during the early 80s was quite exciting, as it was one of the primary duties of the Gurkha garrison in Hong Kong. A Gurkha battalion protected Hong Kong’s land borders and each month, a small team was deployed to the border. Each team consisted of four soldiers and occasionally a dog and handler from the Chinese volunteer corps.

In the early 80s, the difference between Hong Kong and China was pretty stark. While the China side was pitch dark at night, Hong Kong was bright with street lights. Rows after rows of rice fields and thin jungles were visible in China during the daytime. Scores of Chinese in green khakis would arrive by the truckload, work in the area, and disappear before dusk. But 40 years later, those farmlands have morphed into a modern, sophisticated metropolis.

As I got more accustomed to the army's strict discipline, things started getting better for me, and I found army life quite exciting and meaningful. I did my best to learn the skills necessary to enhance my army career and did pretty well despite my relatively weaker physical condition.

But the culture shock we all faced after joining the Gurkhas remained daunting for quite a while. While growing up in Nepal, we only saw and heard positive things about the Gurkhas. They all had lovely clothes, clean faces, properly groomed hair, large radios and tape-recorders, fancy cameras, and gold rings and necklaces. They also married the prettiest girls in the village. We all had the impression that life as a Gurkha must be easy and the money good. Nobody ever talked about the hardship, discipline, and physical and mental endurance the Gurkhas need to go through in the regimented army life.

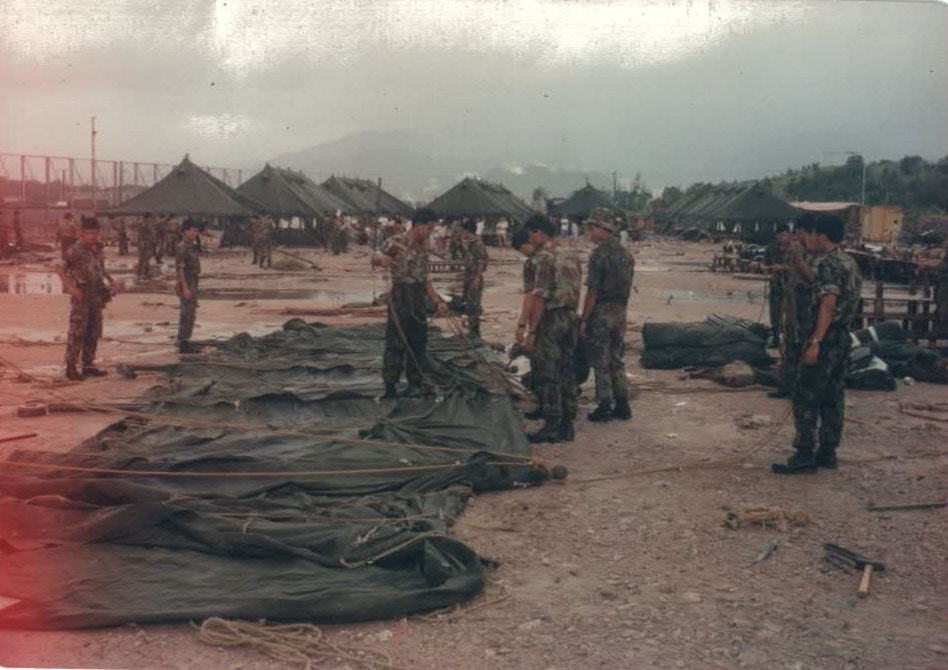

After Hong Kong, the first overseas traveling I did was to Australia in 1981 when we took part in a joint military exercise in Brisbane alongside soldiers from the UK, Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, and New Zealand. We were amazed at how vast Australia was in comparison to Hong Kong and Nepal. I still remember an event that's as vivid today in my memory as it was then. We were in the final stage of the joint military exercise, digging a trench for days in the middle of nowhere. Nobody was allowed to come out of the trenches. On the night of July 29, 1981, we were disturbed by a commotion coming from the company's headquarters. It sounded like a celebration or a party. Of course, we were too insignificant to ask questions, but the truth came out later. What had happened was that all the British officers had gathered to celebrate the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana with champagne. I realized that there were two separate rules for the Gurkhas and the British, although we were part of the same army. It would take me some time before I was able to figure out all of the differences.

READ MORE: Why the Gurkhas are once again staging a hunger strike in the heart of London

The next event that affected me immensely was the Falklands War in 1982. When the Argentines occupied the Falkland Islands, the British sent in troops from the UK. The Gurkha garrison in Hong Kong was put on standby, ready to move out within 48-hours notice. Our battalion commander said to have volunteered for the job, but the priority was always given to the Gurkha battalion in the UK. Hence, the 7th Gurkha Rifles and some members of the Gurkha Signals and Gurkha Engineers went to the Falklands. Of course, we were concerned and anxious but the Falklands War ended in ten weeks, and no one from the Hong Kong garrison was able to take part.

Army life affected me differently than it did my friends and colleagues. Due to my humble upbringing, I was always aware of the value of money. I didn’t drink nor waste my time and money on frivolous things. But as a result, I had fewer friends and preferred spending my spare time reading and writing. It was also the very first time we were away from home for many years, and the desire to see our families and homes was intense.

I translated those feelings into poems, songs, and short stories. Some of my writing was published in Parbate, a Brigade of Gurkhas publication, and even readout on the British Forces Broadcasting Services radio. Before long, my peers knew me as someone who was adept with a pen. In a community where everyone carries guns, this was an anomaly. And although people respected you, at least to your face, in reality, they resented you. Who likes a guy with a pen in the army, anyway?

READ MORE: A story about the Gurkhas from a Gurkha writer

Besides, my unwavering character of speaking my mind didn't go well with my peers, especially my seniors, and my army career was doomed to fail before it had even really begun. In the army, you need to be strong like a horse that can eat, drink, run, and carry heavy loads without a shriek. My skinny body didn’t even meet the basic requirements.

It took me five more years before I realized that I was not suited for the army. Things would start to unravel from thereon but that is a story for another time. I will detail the next phase of my journey, from an army man to a businessman and a writer in part 2 of this article.

***

Tim I Gurung will be detailing his life as a Gurkha and his transition to business and writing in a series of articles for The Record. Watch this space for the next edition.

Tim I Gurung TIM I GURUNG is a novelist, an ex-Gurkha, author of Ayo Gorkhali, an acclaimed book about the Gurkhas. He lives in Hong Kong.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, the digital editor of Nepali Times reflects on starting out writing and in journalism, and provides insight on how to tell stories through video.

Perspectives

Interviews

22 min read

Lessons on living fearlessly from the writer Sulochana Manandhar Dhital

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week, writer and activist Sarita Pariyar offers poignant insight into her own writing journey and the invisible women who inspired her to write.

Writing journeys

7 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, writer and editor Tenzin Dickie discusses writerly doubt and frustration, and drawing strength from good writing.

Writing journeys

13 min read

Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson provides a list of easy tips on how to write better argumentative essays and opinion pieces for newspapers.

Perspectives

18 min read

For Nepalis living abroad, family is always a scattered reality, and every goodbye can feel like the last

Writing journeys

11 min read

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, Kunsaang narrates growing up in the mountains of Humla, studying from books that did not represent her, and writing to remember.