Writing journeys

8 MIN READ

In this edition of Writing Journeys, novelist and translator Manjushree Thapa illustrates her difficulty in getting from draft to draft and her complicated relationship with writing.

This week's essay describes a different kind of Writing Journey. Manjushree Thapa chronicles the journey of a book from a ‘zero’ draft to drafts two, three, four, and beyond. She tells of her journey from excitement to pain and self-doubt and eventually, fitfully, to joy and pride. In several places, she so perfectly captures the frustration of trying to get words on the page that I said to myself, “Yup, been there.” In a couple places, I burst out laughing. It was either that or cry.

The essay is a good reminder that nobody finds writing easy. Also, crucially, it's a good reminder that after pain comes joy.

There's something very reassuring in knowing that even Manjushree Thapa finds writing difficult — and that she sometimes hates it. Maybe I'm not such a slow, incompetent, undisciplined hiker after all. Maybe the road is just steep, very steep.

The essay is also a reminder that serious writers study writing seriously. Manjushree has read and absorbed the advice of Strunk and White, Annie Dillard, and other famous writer-coaches. She re-reads books not just for content but for technique.

The point here is that even those authors we might think of as ‘natural-born writers’ look for and find ways to improve by studying the craft of writing and by reading carefully. Those improvement strategies exist and we can all benefit from them.

I hope you will read this wonderful essay carefully.

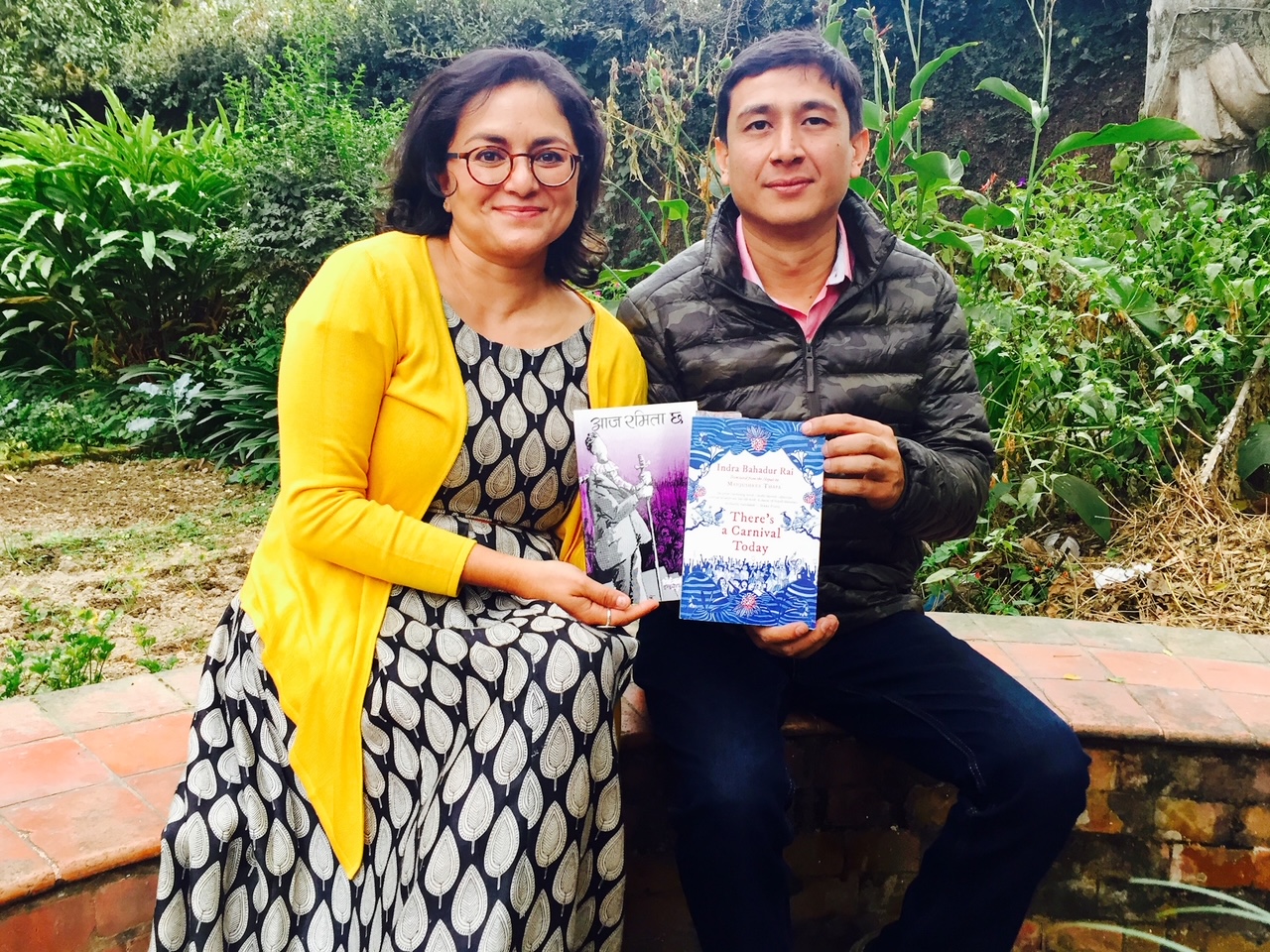

Manjushree Thapa writes fiction and nonfiction, and translates Nepali literature into English. She is author of an excellent history of Nepal, Forget Kathmandu: An Elegy for Democracy. Her last books were All Of Us in Our Own Lives, a novel set in Nepal's aid world, and the translation of Indra Bahadur Rai's There's a Carnival Today. She was born in Kathmandu and lived in Nepal for 49 percent of her life. She currently lives in Toronto. See her writing on The Record: ‘Women have no nationality’.

Writing Journeys appears each Wednesday. In previous weeks, Shradha Ghale described “the sense of being focused” while writing, Kunda Dixit stressed maintaining the “narrative tension”, Niranjan Kunwar noted that “writers write about things they care for”, Kesang Tseten described “the process of seeing how others see or respond to your work”, Sujeev Shakya wrote of “the expanse of the world of books”, Kalpana Jha criticized “undue emphasis on jargon and wordy, complex language,” Janak Raj Sapkota celebrated “how characters can stay in people’s hearts for many years”, and Dipak Gyawali discusses using different color pens to dissect a draft. I also offer four of the most useful skills I have learned.

Coming next week: Three big blunders

***

It never gets easier, but I love writing

I'm working on my umpteenth book right now, and am here to attest that it never gets easier.

This, despite the fact that by now my writing process is well known to me.

I know that I'll love researching a new book, and will enjoy outlining it in what I call a ‘Zero Draft’. This amounts to a detailed chapter-by-chapter breakdown with all of the relevant information, plot lines, characters, settings, timelines, and crude literary elements in place. The Zero Draft takes me anywhere from months to years, during which life feels full of possibility and hope.

I also know I will hate — absolutely hate — writing Draft One.

The first draft of a book is of course necessary to write: it must exist for the manuscript to improve and eventually be completed. It doesn't really have to be good — which is perhaps that's why it's so hard to write. The scribblings of my first draft rarely resemble what I mean to write. I'm plagued by self-doubt, wondering daily what in the name of all that's holy I'm doing with this book, and indeed my life.

If it's at all possible, I try to write Draft One somewhere nice — at a scenic location, or at least outside my study, in the living room, or on the patio. I procrastinate, surf the web, clean the house, update my apps, and do anything except for what I should be doing — till there's really no option. So will pass four to six desperate, unhappy months.

Possibly, I'll hate working on Draft Two and Three as well, but eventually — on Draft Four if I'm lucky — the manuscript will begin to resemble what I had set out to write all along.

From there till the end — another year or two if no unexpected crises arise — my process will be calm, and at times even joyous.

Revision is what infuses my writing process with life. While clarifying and tightening each draft, I can tease out the subtler elements of the manuscript — the imagery, the secondary themes, the rhythm of the prose, its tone and texture, the voices of the characters, and the mood of the overall work. I can discover hidden depths to the story: a backstory to one of the characters that explains their deeper motivations, for example. Or I'll notice a recurring theme, and this can be a revelation to myself. Revision is what breathes ‘prana’, or breath, into my stories, animating them fully.

I love working on the final drafts of my books, when every sentence, every word, counts. There is beauty, at last, in my writing. There is pleasure in my life. I know I'm done when I find myself fussing too much over punctuation. And when I'm done, I forget the agonies of the early drafts and am ready to work on my next book.

What differs between my current process and my process when I started to write in my twenties is that I must now figure out the pragmatics of the writing life. Before starting a book, I must know how long it's going to take me, and how I'll support myself during that time.

What hasn't changed are the basics of writing. I came across Strunk and White's Elements of Style in high school, and no amount of postcolonial theory about empires writing back — thank you, Salman Rushdie — can dislodge its lessons from my heart. Choose your verbs wisely and avoid adverbs. Use active sentences. Do not abide verbosity. Pare each sentence down till every part serves its purpose.

These are not rules of course; they are merely my stylistic preferences. I have also picked up pointers from the countless ‘how-to’ books I've read over the years, be they by authors whose work I greatly admire, like Annie Dillard, or those whose work I don't care for, such as Stephen King. The former taught me to observe the natural world, the latter to avoid alcohol while writing. Umberto Eco taught me about musicality in writing. From Flannery O'Connor I learned to differentiate between the external elements of fiction — manners — and the mystery at the core of each work.

Mainly, though, I've learned to write by reading. I keep certain books on my desk: Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, Don Delillo's Mao II, Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's Dictee. I reread them every few years, but their primary purpose is to remind me of the intimate quality — the quality of the interior monologue — that I aim for in my writing voice.

It is such a privilege to be able to write, and be published, and be read. I take the responsibility to do it well — both ethically and aesthetically — very seriously. Perhaps that's why, after all these years, writing never gets easier.

It really doesn't. Yet I love writing. I really do.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Books

Culture

11 min read

An 11-year-old reads six recently published children’s books and reviews them on her own terms.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week, series editor Tom Robertson reflects on writing and Writing Journeys, and distills everything he’s learned into sound advice.

Perspectives

Interviews

22 min read

Lessons on living fearlessly from the writer Sulochana Manandhar Dhital

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, Kunsaang narrates growing up in the mountains of Humla, studying from books that did not represent her, and writing to remember.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week, reporter and writer Janak Raj Sapkota writes about how his experimentation with colors and his habit of keeping a journal have helped his writing.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, US-based journalist and writer Sanjay Upadhya recounts his time working at The Rising Nepal under the Panchayat and the lessons he’s learned along the way.

Longreads

Features

34 min read

Chitwan National Park has earned international praise for its conservation successes, but it has also evicted indigeneous communities and upended many local livelihoods.

Perspectives

6 min read

When we hide behind ji, dai and didi, ageist and patriarchal relations take over the workspaces, and that is hard to shake off.