Writing journeys

11 MIN READ

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.

This week’s Writing Journey is a charming essay from Richa Bhattarai about her father’s efforts to encourage her and her sister Sewa to learn to write when they were girls. “I began my writing journey with a poem when I was around seven,” Richa tells us.

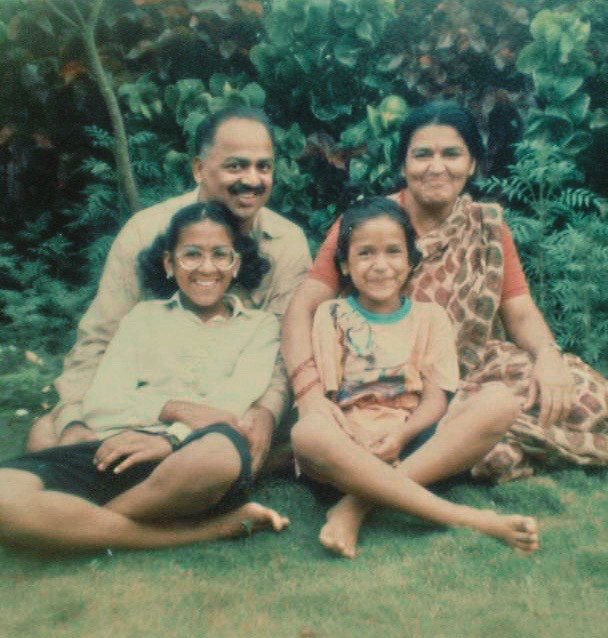

Richa’s father loved books and writing. He shared his love with his daughters, encouraging them from an early age to write — poems, stories, descriptions, and even book reviews. Soon writing became a habit for the two sisters. Richa’s father sometimes pushed, but only gently, often giving them a smile or a few encouraging words. He “celebrated our work,” Richa writes, “as though it were a masterpiece.”

The essay reminds us how transformative reading, writing, and storytelling outside of the school curriculum can be. And it reminds how important encouragement from parents and adults can be.

Such storytelling can take many forms. Akhilesh Upadhyay described in last week’s Writing Journey how radio stories about cricket captivated his imagination as a young boy. My nephew grew to love books — even before he could recognize letters — because of nightly, after dinner “storytime,” which I describe in a Kathmandu Post essay called ‘Teaching the Magic of Books’.

Richa explains how, with some encouragement from her father, she set out at age 11 to write her own book, and soon grew addicted to diary writing. And I know a family that, at holiday times, has all the young cousins work together to write and perform short, funny homemade dramas. They spend weeks, sometimes months, preparing.

Such practice builds skills and confidence. But maybe even more importantly, it creates a lifelong taste, a hunger, for learning and storytelling.

Thanks to Richa — and to Mr. Bhattarai — for inspiring us to share the creative joys of storytelling and writing with young learners.

Richa Bhattarai is a writer and book reviewer from Nepal. Her anthology of short stories for young adults, Fifteen and Thr3e Quarters, was published in 2011. From 2018 to 2019, she wrote the book review column Page Turner for The Kathmandu Post. Her personal essay on friendship during the times of Covid-19 is being published as part of an anthology by Yoda Press in early 2022. She was an executive committee member of the Nepal Literature Festival, the country’s largest literary extravaganza, from 2012 to 2020. You can read more of her writings here.

***

Can writing be taught? Yes, I am evidence.

How many people does it take to teach you to write?

Only one, but he needs to be my father.

I began my writing journey with a poem when I was around seven. The poem was titled ‘My Mummy’, and it was completely plagiarized from our school’s annual magazine. I loved the rhymes of the original poem — ‘My Daddy’ — and simply changed the protagonist’s gender to create a poem of my own. My mother was highly appreciative when I showed it to her, yet I must have sensed something amiss. I tore that page from my notebook and did not think of writing anything other than my homework.

Until one day — I was around 10 — Buwa came home with two identical diaries for me and my sister, Sewa. Mine was a simple gray one with three flowers swirling on the cover.

“You must write one page in this diary every day, and show it to me,” he said.

I did not know what I would write, or even why we were expected to write anything. Buwa gave me ideas in the beginning. I could jot down experiences from the past, my plans, poetry, or book reviews. Of course, I had no idea how to review books, but Buwa had made it clear we could not reach for another novel before writing something about the one we had finished.

So, with great curlicues and flourishes, I began writing. My first piece was almost like a diary entry, detailing my school classes and the quirks of my friends.

That afternoon, after finishing his Ph.D. research for the day, Buwa sat down on one of the folding chairs in our living room. He read my entry, corrected my prepositions, mended my spellings, and suggested better sentence structures, before moving on to Sewa. He also praised us in front of Ama, “Read our daughters’ writings, how beautiful they are.” Ama smiled and read them quietly and with pride, as she does to this day.

About a month after we began writing, Buwa made it clear we couldn’t go out to play with friends unless we completed our entries. “Richa!” “Sewa!” neighbors would call from our gate, a game of hopscotch already underway. We would look out of the windows, furiously placing one word after another, trying to complete our writing assignment. There was no repercussion if we did not finish, save a disappointed frown lurking on Buwa’s forehead. But when we did write a page, he gave us a wide smile and celebrated our work as though it were a masterpiece. We wrote for that smile alone.

In a couple of months, I began experimenting with my writing. I wrote a manual for my Barbie doll to operate her kitchen, then created a magical world based heavily on Alice in Wonderland. I imagined a room of my own and painted vivid pictures alongside descriptions, and then recollected memories of our hometown of Damak. There was a five-page long review of Jane Eyre, a book that had touched me deeply. Poems were my favorite, I still remember this one:

UNO, UNO, how good you are

Stopping the countries from world wars.

Sewa never fails to remind me of my early obsession with the United Nations.

Buwa read each of our entries thoroughly, marking places he thought we could do better, and sometimes setting us simple topics to work on. Once, he began a poem that I had to complete:

Beyond the hills and down below

A poor old man called nasty fellow

I am neither patient nor disciplined by nature and was even more restless as a child. Sometimes the task of writing would loom heavy above my head, as I wondered for the hundredth time WHY we had to write. Why did we have to do this extra lesson that none of my friends had to?

“Writing is the only thing of permanence in this world,” Buwa would say, “Nothing else remains, only our words do.”

So back we went to drafting one more page.

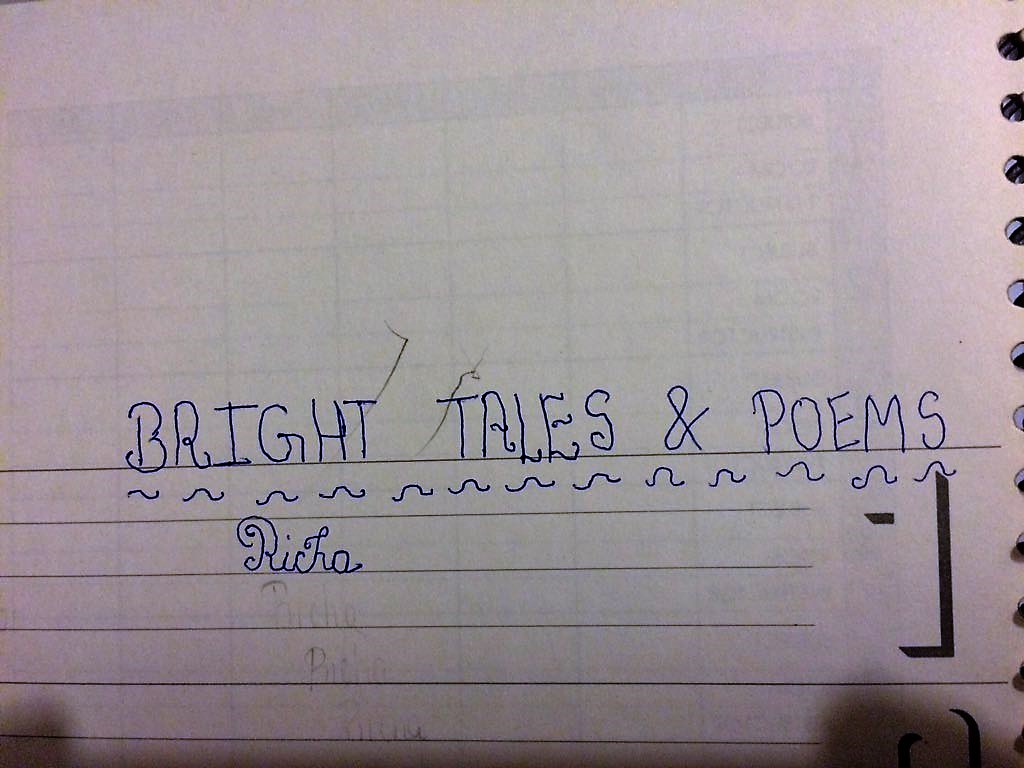

Emboldened by our exercises, at 11, I set out to write my own ‘book.’ I asked Ama for a new diary, wrote ‘Bright Tales & Poems’ on the first page, and proceeded to fill it with my thoughts and rhymes. I also covered an exercise book in brown paper, scrawled ‘Novel’ on the cover, and wrote my novel with Enid Blyton-esque characters busting a conspiracy to sell snake poison. It must have been an outrageous novel, yet all my parents’ friends were excited about my handiwork. At every gathering, Buwa would proudly parade this notebook around. It is sadly lost to the recesses of time.

Then I asked Ama for another diary, and another. In the next 12 years, I would use them to vent my teenage angst and wild ideas. This diary writing became the basis of all writing I would do as an adult. The only difference was that I no longer showed the diaries to Buwa.

However, there were other works I showed him. I started publishing poems and short translations. Then, at the age of 16, I published a personal essay titled ‘Curlilocks’ in The Kathmandu Post. It was a reflection on how my curly hair brought me joy in its uniqueness, and agony through mild adolescent bullying.

I remember how happy Buwa was that day. Then a few months later, Sewa’s essay was published in The Himalayan Times.

“You have both become what I dreamt you would be,” he said, doing a little joyful jig on the front lawn.

Indeed. Other parents might wish their children to be doctors or engineers or government service holders; all our father wanted was that his daughters take to writing. He invested his time and energy and learning to direct us, and I am happy to say that he has succeeded. Today, for both me and Sewa, a day that we do not write is a day wasted. We feverishly compare our writing schedules and productivities and give each other prompts to get over writing blocks.

I do not know when Buwa developed his obsessive love for reading and writing. He grew up in Nepal’s eastern hills, and then the Tarai, briefly moving to Benaras in India for his studies. He had to work to pay his school fees, and there was little inspiration to be found in the fields around him. But at twenty-one, he had already published the novella Muglan, which tells a sad tale of migrant laborers. He has since published several works in Nepali and English.

To me, his real triumph is not his publications but the discipline he follows – any writer around the world would be jealous of him. Often, from four in the morning to eight at night, he sits at his blue escritoire and reads and writes, translates and edits. Procrastination is a concept he does not know.

Buoyed by his dedication, Sewa and I, too, spent hours poring over our writing during our teenage years. By the time I was 23, Buwa was adamant that I must publish a book.

“It is already too late (to be a writer),” he cautioned me.

So as I turned 24, I published Fifteen and Thr3e Quarters, an anthology of short stories for young adults. When I reread it sometime ago, I was sad to note how very flimsy the plots were, how unbelievable the characters, how constricted the language. Today, I remember not the book but Buwa’s wide grin as it was launched. He is still waiting for my second book.

“A person who has been given opportunities yet won’t read and write is bhus (husk),” he says.

His daughters try so hard not to be husk.

Mine is an unusual writing journey, for most writers start writing because they have an urge to, and not because they are urged to.

I enjoy writing book reviews most of all, leaning back after reading a book and analyzing why it pulls me in or puts me off. Sometimes I will pour my heart out in personal essays, musing over the limited space women have in Nepali culture, or how a job could mean a new life for a Nepali woman. I write about my life and times, and then I write short stories that are implausible and dramatic. I was brought up on Roald Dahl, O. Henry, and Saki, and I strive ardently to recreate the slick endings of their stories.

I also have other favorite writers and books now: Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, Sally Rooney’s Normal People, Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, Madhuri Vijay’s The Far Field. Books by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, P.G. Wodehouse, Elif Shafak, Amitabh Ghosh, Barbara Kingsolver, Kamila Shamsie, Ann Patchett, and Anuradha Roy.

When I read them, then write afterwards, I feel content that my father has taught me to appreciate literature. Writing, especially, has served me well at work, it has been my therapy, and it has helped me speak up about things I’ve desperately wanted to. Most of all, my experience has proven that writing skills can and should be taught from an early age.

So to all parents wondering if you can teach your children to write, you certainly can. All it takes is a lot of time, and an extra portion of patience.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

10 min read

Water expert Ajaya Dixit recounts his writing journey of learning to bridge the gap between the natural and social sciences.

Features

7 min read

Amid a proliferation of cheap, fast fashion clothing, young Nepalis are turning to conscious clothing and shopping for second-hand apparel.

Writing journeys

11 min read

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson is back to identify eight common mistakes and provide Tom’s Twelve Tips on writing better sentences.

Writing journeys

8 min read

In this edition of Writing Journeys, novelist and translator Manjushree Thapa illustrates her difficulty in getting from draft to draft and her complicated relationship with writing.

Perspectives

18 min read

For Nepalis living abroad, family is always a scattered reality, and every goodbye can feel like the last

Writing journeys

6 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson takes apart an older article of his, line-by-line, providing critical insight into what makes a good essay.

Perspectives

11 min read

The acceptance speech of writer Yogesh Raj who received the 2018/2019 Madan Puraskar for his historical fiction, Ranahaar.