Explainers

3 MIN READ

Millions cannot get citizenship certificates, as political parties fail to pass the Citizenship Bill.

The Citizenship Bill, tabled in the House of Representatives a year ago, remains stuck there, as political parties remain divided on provisions in the bill.

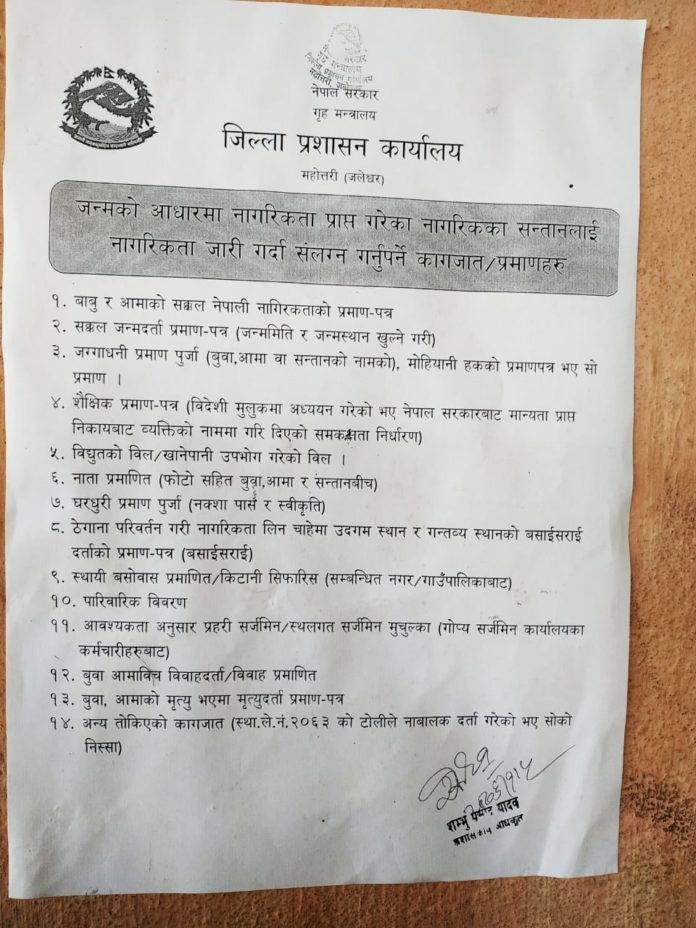

In the new constitution, some provisions on citizenship require a federal law, and there are some provisions that contradict those of the Citizenship Act 2006. Without a revised law governing the regulation of citizenship, it is not clear who has jurisdiction and how people applying for papers -- either through birth or naturalisation -- are to be treated.

This year alone, hundreds of people have tried -- and failed -- to get their citizenship papers. The few who can, have taken their cases to the Supreme Court. But in the apex court, there is a confusion that would be comical, if it did not have such terrible effects on people’s lives.

This is what has happened in the last five months:

At stake is not just clarity from the Supreme Court in this critical constitutional matter, but the question of how the state treats people. A December 2015 study by the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FLWD) estimated that 5.4 million people in Nepal do not have citizenship certificates -- almost a quarter of the country’s population aged 16 and above. FWLD projects that the estimate (5.4 million), might reach 6.7 million by 2021, which would equal 26.14 percent of the total population.

What everyone without papers has in common is that they are unable to vote, register marriages or births, buy or sell land, appear for technical or professional exams, open bank accounts, gain access to credit, and receive state social benefits. They are denied access to their fundamental rights and to essential state services. The strain this places on individuals and families can be unbearable. The Tarai Human Rights Defenders Alliance has recorded at least one case of suicide that it believes resulted from the distress of being repeatedly refused citizenship papers.

Even when people are able to invest the time and effort and resources to go to the Supreme Court and win, this means little. Arjun Sah of Mahottari successfully sued the government to be eligible for naturalised citizenship. He filed his case against the government in the apex court on February 18, 2013 and the final verdict was delivered on August 21, 2018.

“Three months ago, I submitted the required papers to the Home Ministry following the verdict,” he said. “An official informed me that a meeting will be held to issue the certificate.”

It seems the ministry still is dragging its feet on issuing his papers. “Your citizenship certificate will be issued soon after the enactment of the law,” he added quoting the official.

:::

We welcome your comments. Please write to us at connect@recordnepal.com

Praveen Kumar Yadav Praveen Kumar Yadav writes on the contemporary issues of development, politics, human rights and social justice. He tweets at @iprav33n

Features

3 min read

Shortage of protective gears, supplies and ventilators in Nepal likely to cripple medical interventions against Covid19

Perspectives

7 min read

Ensuring the code of conduct is followed, that candidacies are inclusive, and the expense ceiling is adhered to are as important as ensuring that elections are peaceful.

Features

6 min read

With local elections just three days away, here’s a look at two candidates most likely to win Lalitpur Metropolitan City’s mayorship.

Features

5 min read

As no formal orders have been placed and no agreements drawn up, even the Health Minister is looking to the gods.

COVID19

Explainers

6 min read

The Record explains how the Covishield vaccine works and how the government will roll out the first million doses

Features

5 min read

NCP faction names Madhav Kumar Nepal as the party chief to replace KP Oli as Oli expands the party’s central committee by incorporating his loyalists

Perspectives

8 min read

The ongoing border dispute, inflamed by India, has given back the reins of the country to an otherwise faltering premier

Explainers

9 min read

Fact-checking viral video clip reading “Students in Butwal stage huge demonstration against India claiming Kalapani and Lipulekh is ours”.