Features

9 MIN READ

From programming the first computer able to read Devanagari to developing low-energy desktops that are used in telemedicine, Shakya’s contributions are manifold.

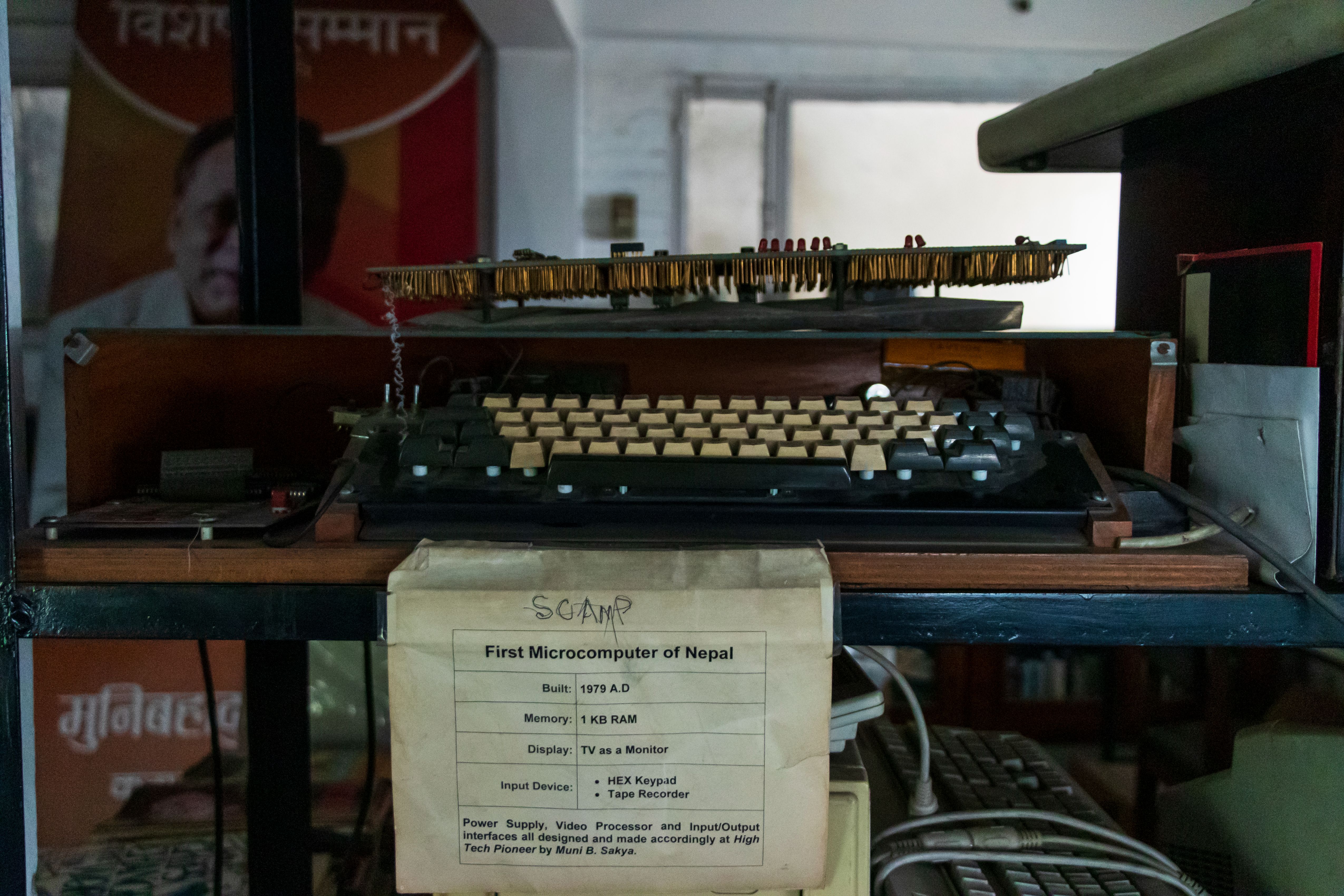

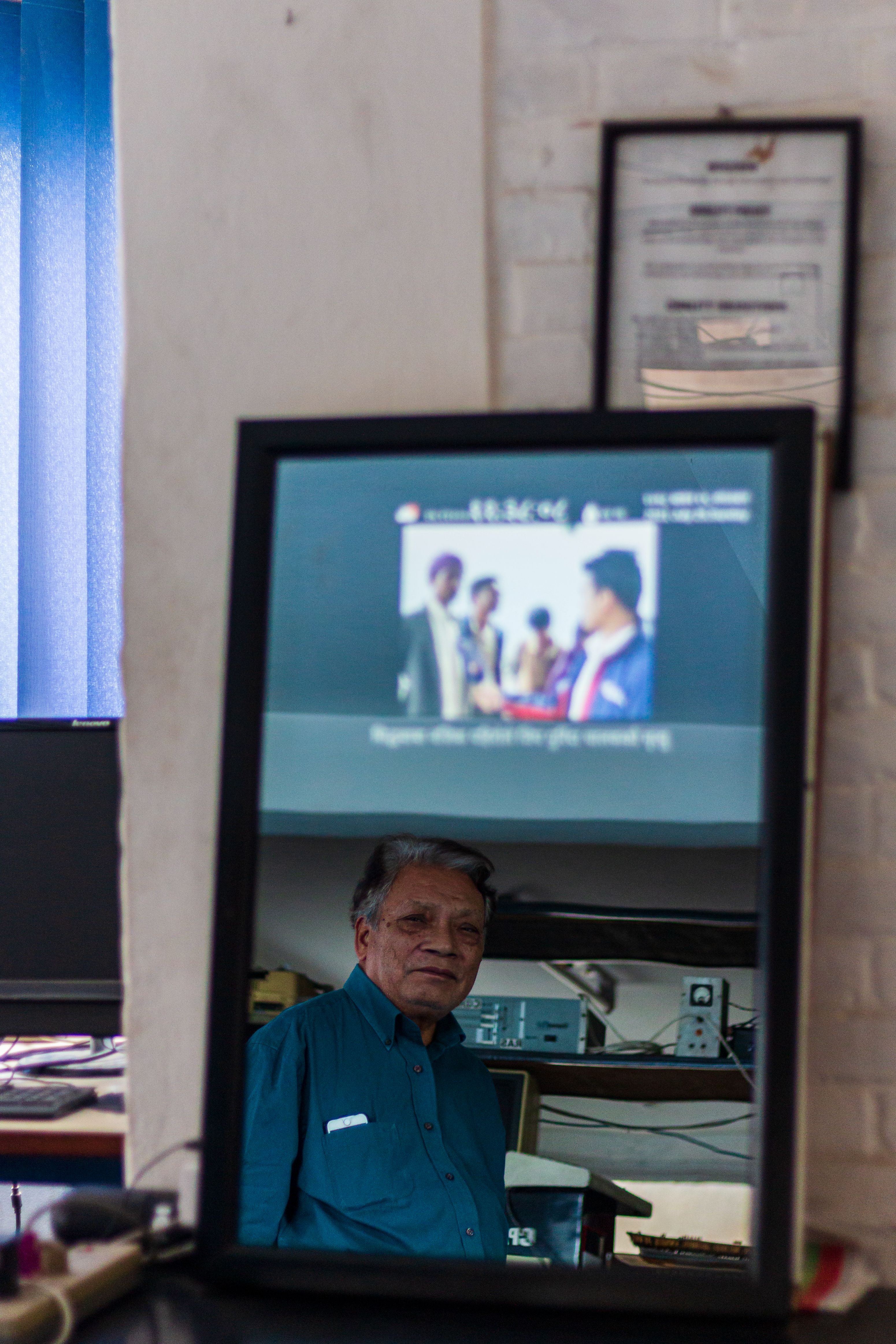

Muni Bahadur Shakya clears the dust off of what is reportedly Nepal’s first micro-computer with a mighty blow. This prototypical desktop computer is basically a typewriter with a maze of transistors, microchips, and circuitry attached to it. It connects to a television for its monitor. Shakya, widely considered Nepal’s first IT engineer, built the microcomputer himself in 1979, with parts collected from around the world.

That same year, his creation was showcased at a ‘UN convention’ held at the Blue Star Hotel in Kathmandu, and the computer was unofficially named the “UN computer” due to the fact that its parts had been sourced from around the world, says Shakya. The wood frame was carved in Nepal, glass crafted in India, switches made in China, and the microprocessor brought from England — everything assembled in Nepal by Shakya with practical skills gained in France.

“At that time, you could rarely see a micro-computer in all of South Asia. Even France was only getting started with personal computers then,” says 81-year-old Shakya.

Shakya is a Nepali computer science pioneer. Ever since the 80s, when most of the country had yet to even see a computer in person, Shakya has been innovating in the field of computers. From programming the first computer able to read Devanagari to developing low-energy desktops that are used in telemedicine, Shakya has contributed much to the nascent computers sector in Nepal.

From a very young age, Shakya was always interested in science, particularly physics. When he was around 12 years old, Shakya came up with his first invention — a telescope made out of his grandfather’s spectacle lenses.

“I was overwhelmed with joy when I finally found a glass with a meter-long focal length for the telescope. The view of Jupiter’s moons, Mars, and other planets was magical,” he recalls.

In 1961, when he heard of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin reaching the vast abyss of space for the first time in human history, Shakya knew what his passion would be. So inspired, he decided to pursue an intermediate education in science at Tri-Chandra College. Shakya eventually moved to Calcutta in India to pursue a diploma in radio engineering. On his return to Nepal, he was hired by the Radio Nepal Transmission Station, then based in Khumaltar.

At Radio Nepal, Shakya got a chance to work alongside British engineers on a collaborative project. Shakya says that the British were so impressed with him that they managed to get him a scholarship to study engineering in England.

In 1970, Shakya found himself in London studying Electronics and Broadcast Engineering at the London School of English. After concluding his studies, he received an offer to work in England as an engineer but Shakya refused.

“I learned a lot there but I always wanted to come back to my country,” said Shakya.

Shakya returned to Nepal and resumed work at Radio Nepal. However, he had returned with a newfound hunger to learn about computers. In England, he had recognized the potential the device held.

“I had seen a supercomputer [in England] that took up an entire room, but the microcomputer was the new big thing. I wanted to help create computers that can be used by individuals,” said Shakya.

Shakya continued his studies in France, receiving a scholarship from the French government for a training program working with mainframe computers.

After returning to Nepal in 1978, Shakya began assembling his first micro-computer. He had purchased all the necessary parts while studying in England and France — a microprocessor, a hex keyboard, 1Kb RAM, a CRT TV for display, and some microchips for interfacing. Shakya built the power supply and video card by himself.

“This thing called dedication, it’s something special. I don’t know where it comes from, but that’s what has pushed me since my childhood. Several days and sleepless nights were spent on making and operating the micro-computer,” says Shakya.

In 1979, when Shakya finally got his micro-computer up and running, he received much acclaim. Newspapers including The Rising Nepal and Xinhua, the Chinese news agency, published feature reports on his computer, says Shakya. All the coverage brought him new opportunities. He began exchanging letters with an American named Jonathan Lyndell, who had come to know about Shakya through the news. Lyndell promised to assist him in his further studies and once again, Shakya was able to go abroad to study computers. In 1980, Shakya landed in Minnesota to study computers through Lyndell’s help.

In the United States, Shakya absorbed information like a sponge, he says, grasping everything they were working on and further honing his skills through practice and rigor. Shakya became a technical lead in developing information computer hardware at MTS Systems Corporation in Minnesota, working to innovate a 900KB floppy disk when 80KB disks were the standard.

“My fate took me to many places solely on the efforts I made at various institutions. I would work late into the night and frequently, the chairman himself would personally come to let me know that I should go home. I was known as an employee who had no time limits,” he says.

For three years, Shakya worked in the US. While there, he visited Silicon Valley and saw how XT, the first IBM computer with a hard drive, was produced. In 1983, he returned to Nepal with 16 boxes of computer parts. This time around, Shakya wanted to develop a computer that could operate in the Nepali script. He established his own company, Hi-Tech Pioneer Pvt. Ltd., and soon developed the first personal computer that could read and display Devanagari script.

“All computers operated in English, but I wanted to create a computer that also understands Nepali. Nepali language fonts aren’t as simple as English alphabets. The characters in Devanagari are very intricate. Many of the characters had to be painstakingly hand-drawn,” says Shakya.

He conducted a demonstration of his Devanagari computer at the National Planning Commission in 1983.

“People were astounded to see a computer that operated in our national language. The first sentence that was displayed on the computer was our then national anthem, श्रीमान् गम्भीर (Shriman Gambhir). That was one of my proudest moments as a Nepali,” he says.

In 1985, two years later, the Agriculture Development Bank commissioned 19 computers, one for each branch, with Shakya’s Devanagari script installed. The computers were used to input customer names in Nepali.

Shakya also managed to integrate new phonetic techniques into a card he had brought from Silicon Valley, incorporating it into a computer to speak rudimentary Nepali. After learning about the supply chain operating in Taiwan, he even visited the country more than 20 times to learn more. His name proved to be a blessing in Taiwan, as the majority Buddhist country related him with the Shakyamuni Siddhartha Gautam. He was even allowed to enter the factories and photograph the motherboards that were being produced there.

“If my name was Ram Bahadur instead of Muni Shakya, then I might not have received such permission to photograph,” Shakya laughs.

He would later use these photographs to position his own chips into a motherboard.

His achievements brought Shakya much fame. Ministers would visit him and promise to develop computers and the IT field in Nepal, he says. But none of them followed through.

“My dream was to establish a new Silicon Valley in my country,” he says. “There are still possibilities for Nepal but neither the government nor anyone else took any interest or supported me in my endeavors. To this day, Nepal still lacks significant ICT infrastructure and only allocates a minuscule budget for its development.”

Regardless, Shakya has continued to work in the field that he is so passionate about. In 2006, Shakya devised a supercomputer from a cluster of 16 computers to conduct data-heavy tasks such as weather forecasting and financial analysis. He has also built ‘green computers’ that only consume 35 watts of power, six times lower than the average desktop computer, and at half the price of a regular laptop. These computers are currently in operation at telemedicine centers in Jajarkot, Kalikot, Bajura, and Dhading.

Although Nepal is now firmly lodged in the IT-sphere, it took a long time for Shakya’s achievements to be formally recognized. In 2005, he received an award from the Royal Nepal Academy of Science & Technology (RONAST) and in 2012, he received the Business Excellence Award from the Computer Association of Nepal (CAN) Federation. In 2016, Shakya was awarded the ICT Pioneer Award for his contributions to Nepal’s IT and computers sector.

“At a time when the world was still in the developmental phase of computer technology, he [Shakya] returned from abroad with knowledge and parts for making computers and set a new precedent by demonstrating to everyone that it was possible for computers to be built in Nepal,” says Rajan Lamsal, chair of the ICT Award committee.

Although Nepal has made major strides in telecommunications, mobile connectivity, software outsourcing, and skilled human resource production, much more needs to be done to harness the country’s potential in ICT, says Lamsal. Nepal lags far behind in the UN International Telecommunications Union’s ICT Development Index. In 2017, the last time the index was developed, Nepal ranked 140th out of 176 countries.

Meanwhile, Shakya, even at 81 years of age, continues to innovate. He shows no signs of slowing down and has a number of projects in the pipeline, including a magic mirror that can display the news, provide weather forecasts, and even answer basic questions.

“If I was after money, I could’ve become a billionaire by now, but that was never my intention,” says Shakya. “If only the government had supported me, thousands of people would have gotten jobs, maybe even come up with new inventions. Nepal could’ve become a leader in computers.”

Aishwarya Baidar Aishwarya Baidar is a fashion blogger and a media studies student at Kathmandu University.

Opinions

5 min read

The privileged must do more to facilitate and encourage discussions around the abuse and othering of the marginalized and systemically oppressed

COVID19

Perspectives

5 min read

The world’s largest missionary movement cannot be blamed exclusively for its role in the Covid19 pandemic

Features

Longreads

32 min read

Is maintaining the Kodari crossing between Nepal and China as an international highway a lost cause?

Podcast

History Series

2 min read

A young prince from Gorkha sets his mind to conquer the valley of Kathmandu

Features

6 min read

The Record introduces a new mini-series where we speak to artists from various fields and ask them about the projects they worked on during the lockdown and the pandemic.

Podcast

History Series

1 min read

Juddha faces resistance from the Rana family, the Nepali dissenters, and the British India

Features

11 min read

Caste is such a system of organization and thought that it creates division and discrimination between oppressed groups, to the extent of even abusing their human rights.

COVID19

Perspectives

6 min read

The lockdown presents us with the opportunity to be more innovative and resourceful as educators