Interviews

Longreads

16 MIN READ

An interview with China expert Andrew Nathan on China and its neighborhood

China is a vast subject. And there are countless schools of thought, historical references, and philosophies to explain China, a country of 1.4 billion people, whose 5,000 years of unbroken civilization and the phenomenal rise make it both a political and a cultural enigma worth understanding. To a South Asian next door, the interest in China becomes more than academic.

The influence of Confucian thought points at the Chinese inclination for consensus and compromises (“win-win situation”). The Art of War by Sun Tzu tells the Chinese to keep a low profile while you gather your strength and avenge the enemy without them knowing you are powerful. There’s the historical burden on China of imperial Britain, which waged a long war to get access to a vast market through gunboats and firepower, ultimately subjecting millions of Chinese to opium addiction.

When the early 19-century war between Britain and China ended on 17 August 1842, with the Treaty of Nanking, the Chinese were forced to accept the British to “carry on their mercantile transactions with whatever persons they please.” It committed China to free trade, and free trade, like it or not, in opium, too.

Perhaps the most well-known modern western writer on China is Henry Kissinger — a former US Secretary of State, Nobel Laureate, and prolific author. A proponent of realpolitik, he negotiated the Paris accords to end the Vietnam War, made the détente with the Soviet Union possible, and laid the groundwork for the visit of US President Richard Nixon to China in 1972 to normalize relations with the Middle Kingdom.

Some see Kissinger as dutifully defending the Chinese side of the story and his politics (guided by realpolitik calculations) take precedence over the normative value system underpinned on human rights, freedom of expression and assembly, and democracy.

Professor Andrew Nathan’s writings, at least the recent ones, on the other hand, offer a strong normative stand. Nathan himself is no lightweight. He has authored numerous groundbreaking books on China and is one of the most respected and widely cited authors on China. His most recent book, China’s Search for Security (2012), talks about China’s perceived insecurity, including in its neighborhood, despite its phenomenal rise as a military and economic power.

Professor Nathan was in Kathmandu this month to attend an international conference on Dalits. We spoke at length about China; his scholarship is vast and encompasses issues related to China on a global scale.

AU: What brings you here, your first visit since 1964?

AN: I came to participate in the Suvash Darnal award ceremony. We met with a few think tanks here that are promoting democracy.

AU: I want to take you back to your last visit. Nepal was in a different era, we were still a closed society, things that are now enshrined in the constitution — fundamental rights, for example, weren’t there. How is Nepal different in 2018 compared to 1964?

AN: I am not a Nepal expert but I get the sense that changes in the physical landscape are matched by changes in the social and political landscape. But I do remember when I was in here 1964, Kathmandu was like a medieval European city. The streets were narrow and the buildings were 2-3 stories, made out of wood and clay of some kind. The city has now spread out and it’s full of motor vehicles and it’s full of economic entrepreneurship and dynamism with a bit of a lack of attention to the public commons—saw the piles of garbage because everyone is busy running around and pursuing their own economic development.

So you can see a physical change, and I do sense, just from being here for a short few days, vibrant freedom of the press, academia, CSOs [civil society organizations], and the mobilization of marginalized communities. This is not something that happens automatically as a result of modernization. The mobilization takes huge efforts by people like Suvash [Darnal], Sarita [Pariyar], and their circle of friends [in reference to the Dalit conference he attended]. These things take tremendous amounts of effort. The feeling I get is that the people are awake and there is great dynamism and struggle for freedoms. It’s quite an inspiring picture.

AU: On China now, if I may, and to your area of expertise. Do you realize that Nepalis and a large part of Asia, do not share the western ambivalence towards China?

AN: In India, there is a lot of suspicion of China. It differs country-by-country. Vietnam, Taiwan, Japan, India, and even Russia, under the surface, have a lot of reluctance regarding the rise of China. Although they are hesitant to wind up with the US — for example, India, which shares an interest with neither. In some of the other countries — Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and much of Africa, and many parts of Latin America and the Middle East — US concern regarding the rise of China is not shared for three reasons. One is that these countries see an opportunity to benefit from Chinese economic prosperity. Second, these countries don’t have a strategic interest with China. Like India, it has a disputed boundary with China. Nepal does not have boundary issues with China. Thirdly, a lot of countries think that what China may do is no different from what the US already does. That the US is no different from China; it is a great power that exerts influence in legitimate and illegitimate ways. It is self-interested; China is no different. So yes, I do realize that the American view of China is not shared by all the countries and certainly not by Nepal.

AU: How would the rise of China affect its periphery, the neighborhood? Will the Chinese investment come inherently with a certain value system?

AN: Coming from academia, when I hear a question like that, I need to break it down analytically into many parts. Chinese periphery is enormous geographically.

AU: Let’s focus on South and East Asia for our convenience.

AN: If I give an analysis focused on Nepal, it wouldn’t apply to Pakistan or Myanmar. I could start out with Nepal.

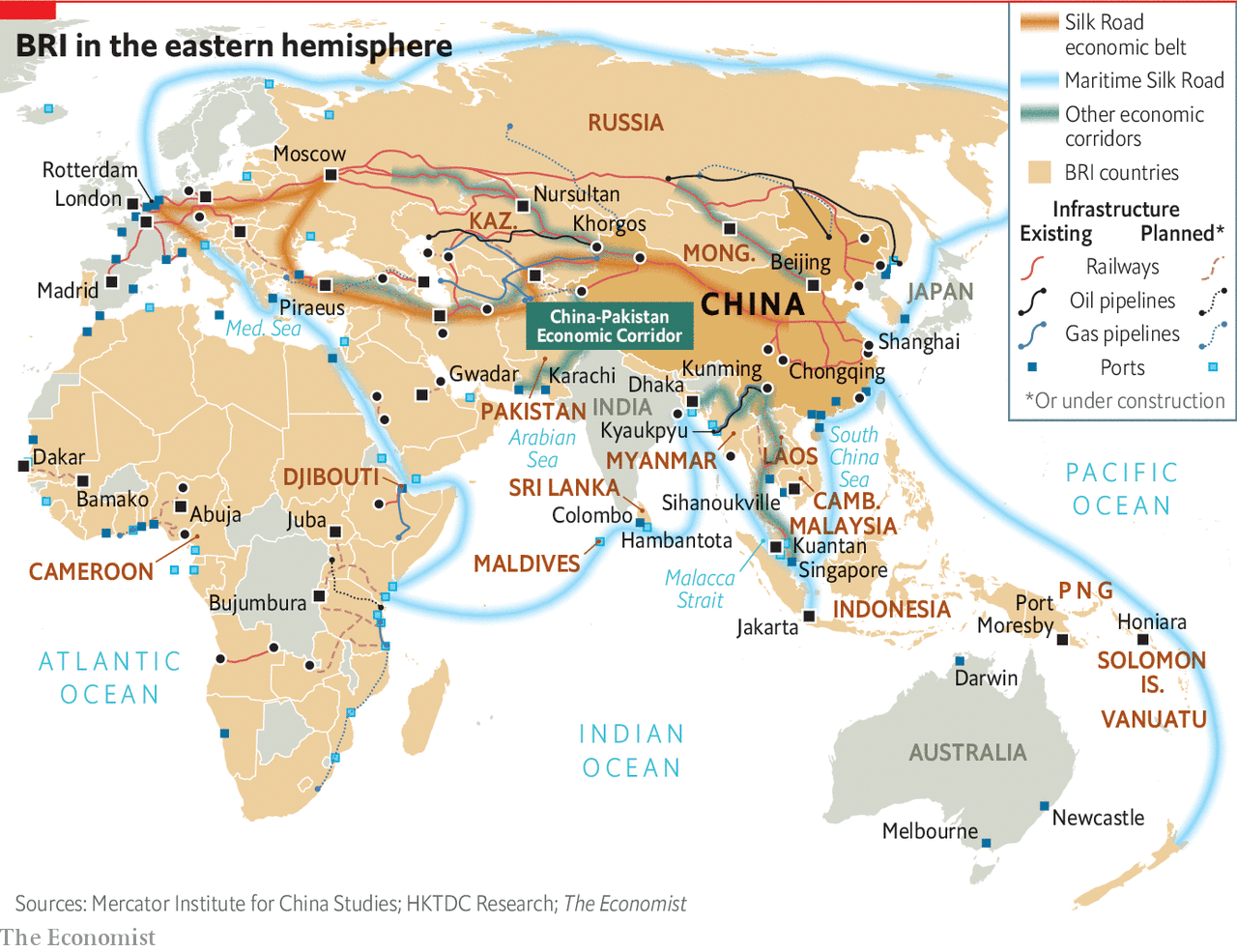

In some cases, the rise of China affects other countries very powerfully in terms of trade and economics; for example, Myanmar. Chinese trade with Myanmar is huge. China is importing jade and tea; there is a lot of movement across the border. Entrepreneurs are coming into Myanmar, China is building a railway to the coast of Myanmar. One Burmese scholar called Myanmar “China’s California,” meaning it is like the West Coast of China — as the country grows, Myanmar will hardly have any independent character.

Nepal is different because of the mountains. And even if the trans-Himalayan railway is built, and as far as I understand, the capacity of any railways is limited. Hard for me to see, that China will ever, or certainly not for a long time, replace India as Nepal’s primary outside economic partner. But it will play a larger role than it has done in the past. Another special feature of Nepal is that it borders Tibet; it ties into the “Tibet problem,” which doesn’t apply to Myanmar or Pakistan — which is tied into the Xinjian Uighur problem, which is not a thing that implicates Nepal at all.

AU: China is already the largest contributor of FDI to Nepal, and the investment is mainly on energy and infrastructure. Nepal is now a signatory to BRI.

AN: Here is a question about the careful analysis of benefits of each of the projects. From my general knowledge, there is a tendency to take the money deal, it does seem to me that there is fine print that’s important. Financial viability of the railway — who is responsible for the financial risks? The Sri Lanka port, for example — who bears the loss at Hambantota? The environmental and human impact? The due diligence of the project impact, when you have to move people off? Does that conform with social values or the China contractors come and just do it?

I want to mention that the financial structure, environmental and human impact, and whether or not the project contributes to human capital formation in Nepal — do they hire Nepal engineers and construction firms or not? They are also worried about it in other countries. I am not saying the World Bank or Asian Development or American investment is beautiful. There are problems with any foreign investment project. Over the last 2-3 decades, there has been some raising of the standards globally of best practices in infrastructure development. There is concern that so far, China hasn’t exercised these best practices. There is the Hambantota case, the Burmese copper mine, Colombia, and African mining.

The Malaysia case [two BRI infrastructure projects have just been canceled by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad] brings another example related to corruption. In many cases in these projects, the China model is famous for getting the job done; for example, with land acquisition. Sometimes that goes along with corruption, that corruption can confuse your politicos.

AU: Broadly speaking, India has been the dominant power in South Asia by a distance. For smaller South Asian countries, China, already a South Asian player, offers them leverage as a counterweight to the Indian asymmetry. How do you see the new South Asian regionalism evolving in view of China’s rise as a great power in a region dominated by India?

AN: US and Japan are also players and perhaps not as generous, or assertive. The natural mechanism is to balance. The smaller powers welcome any other power that comes in to compete with India to prevent economic and political domination. So this is an opportunity and I guess the thing is to use it skillfully. Two things to be avoided: First, not to tip too far over to China — don’t jump from the frying pan to the fire to make yourself vulnerable to somebody else. Two, India won’t go away. So one needs to maintain cooperative relations with India. The politicians have to be very careful in their balancing act because the goal of Nepal, Sri Lanka, and others is autonomy, the maximum amount of autonomy in both a strategic and economic sense. If you have the value of inclusion and India is pushing Hindu essentialism and if you have a culture of religious freedom and China wants you to repress the Tibetan community, you don’t want to do that either. As much as possible, you have to preserve your values.

AU: The traditional South Asian security architecture is clearly in flux. Granted, China is physically across the Himalaya but there is a lot of connectivity already — there are now 56 flights a week connecting Kathmandu with various Chinese cities.

AN: There is a human connection but not a tremendous freight load.

AU: That brings us to the Kerung-Kathmandu railways. There is a lot of expectation regarding the railways, perhaps the most important project in Nepal-China bilateral cooperation. Would it change the geopolitics of South Asia, as many see it?

AN: I don’t think it would make a revolution in China’s economic calculation.

AU: Nepal should get a greater number of Chinese tourists and the volume freight load will substantially increase…

AN: There are flights already. I agree it’s a big deal for Nepal, but it won’t revolutionize the regional system.

AU: Does China see this as an overland artery to connect the larger South Asia? Would it just serve Nepal?

AN: China has its own connection to Pakistan. It doesn’t need this railway for Pakistan. And the sea-lanes to India are cheaper. My sense is that they won’t be using this railway for major amounts of exports to India. If you manufacture the product in Guandong and ship it to Lhasa and Kathmandu, it’s expensive.

AU: China is also trying to shift its supply chain westward…

AN: If you’re saying that they will turn Tibet into a factory export zone, I doubt it. I haven’t heard about that plan.

AU: Alternative inland connectivity, the CPEC [China Pakistan Economic Corridor] and the trans-Himalayan railways, etc, will in the long term give them options to better overcome the Malacca Dilemma, as a Chinese scholar told me during a recent interview in Beijing?

AN: They would have to overcome the Malacca Dilemma but they would never overcome it. So they are building pipelines in Central Asia, they are building pipelines in Pakistan and Burma. Still, the capacity of the pipeline is limited. I can’t give you a number; the pipelines can [only] carry 10-15% Chinese gas and oil import. The Malacca Dilemma is not going to go away.

AU: So as China’s influence grows in South Asia and globally, China’s major concern would be to secure its maritime routes [for energy security and trade], not so much the land routes?

AN: When it comes to the maritime routes, there are four parts to it. There is the South China Sea, the Malacca Strait, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf. The Indian Ocean, in my humble opinion, China will never adequately control it. They may have some presence. The Indian Navy has the Indian coast, they have Andaman and the Nicobar Islands. The Americans have their base in Diego Garcia. It’s impossible for the Chinese to dominate the Indian Ocean. They can dominate the South China Sea; that’s the only part they can dominate. They need peace amongst the great powers for the rest of that thing to be safe. Of course, you can build pipelines to diversify various energy options to reduce dependency on maritime routes but that dependency is not going to disappear.

AU: So what is the Chinese priority?

Hard to say; all have to be done — build the pipelines, strengthen their presence in the South China Sea, try to influence the Malacca Strait states [Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia]. When you put the railway from Lhasa to Kathmandu into that picture, I don’t think that railway is even part of that picture. We are talking about a big energy security picture. The railway is not part of that. Nepal is not an exporter of energy; potentially hydro but that’s it.

AU: How do you see the great-power balance playing out in South Asia? China regards Pakistan as its 'all-weather' friend, China and Pakistan are both committed to CPEC, there’s the traditional rivalry between Pakistan and India, and smaller countries in South Asia, like us, are strongly drawn towards a strong China. And the US regards India as a democracy, representing similar values, and a strategic ally in the region.

AN: You are interested in foreign-policy alignment. Foreign-policy alignment breaks down in various aspects. Economically, all the countries will strive to benefit from economic prosperity. The influences of all these countries are somewhat subtle. In the Cold War, the Soviet Union wanted to install a model of government everywhere and the US fought against it. It’s not happening now. There is an ideological battle but it’s not a 100% battle where each side is trying to install its mode. So in Sri Lanka or any of these countries, the Chinese are willing to work with whoever is in power. It’s an opportunity for South Asian countries to protect their own values, whatever they are. Inside of each country, there is a struggle over values. In Sri Lanka, there is a struggle over liberal inclusive values versus Sinhala supremacy.

AU: How could Nepal benefit from China’s rise and yet not get caught up in the great-power game and make most of the investments?

AN: Be a hard bargainer, have your bottom line at the project level. Second, to have a bottom line on your political values. With these two, you can benefit from Chinese investment without harming your autonomy and your own interests. It should be the same when you deal with the US, Japan, or India.

AU: How does Nepal balance its two most important bilateral ties — with India and with China, both giants?

AN: Nepal is not that small of a country, you’re what, the number 39th by population? Comparatively, two giants who aren’t sleeping anymore. At the same time, you’re not sleeping anymore either. You have a vibrant politics, incredibly aspirant intelligentsia, you have the opportunity to balance between four, if not five powers. Two giants, India and China; Japan, US, and UK — maybe don’t think of yourself as so helpless and small.

AU: How about the United Nations and other international agencies? Multilateralism is beneficial for smaller countries.

AN: I agree. It depends on getting your own act together, what your bottom lines are.

AU: Going back to China, what is it that the West doesn’t understand about China and how does it avoid potentially costly mistakes?

AN: The West doesn’t understand, this sense of China’s vulnerability. That is why in my most recent book “China’s Search for Security,” they are searching for security, they feel threatened by the environment. You are portraying them as this behemoth, which is true as well. From their perspective, they are struggling to defend their regime, their territory, their energy security — against a very difficult environment. So that’s one thing the US doesn’t understand. This vulnerability and this inherent limitation on the Chinese power because they are surrounded by other states, some of which are very, very strong like Russia and India, Japan, and others like Vietnam. Another thing — my understanding of China comes a little bit from a special perspective as I have always been involved in human rights work and I have placed in my own career more emphasis on my intellectual journey — I understand China a lot from the point of view of independent Chinese people who are not part of the government. I know a lot of Chinese who are independent thinkers and have a diversity of opinions.

AU: What else, according to your observation, are Western misconceptions of China?

AN: Part of it is the fault of the Chinese government that seeks to control what the West knows about China. You’ll find things written in the US and UK that irritate me that profess what the Chinese think, it’s based on a cultivated Chinese apparatus, which is huge—think tanks, academics in line with the Government. When you go to China, everyone tells you the same thing. The people you meet are unified in their point of view. That’s true of the Westerners, whether it’s Kissinger or Leonard, everyone has the same narrative.

China has a foreign policy discourse, in fact, they have several — we are the China that defends the liberal international order. We defend the principle of sovereignty, of free trade, that all countries are equal and all should benefit. That it’s the United States who violates these principles. It is a good argument because it has been violated. That’s a discourse that’s appealing. China has a discourse that we are a developing country. They have one that says China’s foreign policy is ethical, that it’s founded on Confucian principles of peace, moral reciprocity, and cooperative understanding. It’s not based upon 800 pages of legal documents that the lawyers negotiated, it’s based upon trust — that’s the kind of Confucian idea.

AU: There are several models of governance: neo-totalitarian, authoritarian, semi-democracy, etc. Where is China headed?

AN: Some people think that Xi’s regime is unstable. I don’t hold that view. I view it as very, very stable. Why do you call it stable? Now he is going to stay in office for another 10 years, I don’t think anyone would challenge him or there will be any social uprising against it. That’s what I mean by stable. If I am correct about that, then the notion is that there isn’t going to be any kind of democracy from below. There used to be some people who thought Xi would introduce democratization from above, I don’t believe that either. So that rules out the scenario of democratization.

So then you have the other two: authoritarianism and neo-totalitarianism. I would say that what Xi is building and what he will continue to build is a vigorous Leninist party state, a core communist party of 90 million people who are very disciplined, that coordinates the activities of a large state apparatus, which is highly technocratic and suppresses all challenges. I don’t think the Xi regime aspires to bring back Maoism or Stalinism. But if it is authoritarianism, it’s a very hard authoritarian system It’s not a system interested in political reform in a liberalizing direction.

AU: How would that affect the way the Chinese conduct their foreign policy?

AN: There are two sides to the question. One about the substance of their foreign policy goals. In terms of the 'how' question, the style or manner in which they carry out their foreign policy. I had urged you before that you need to have your bottom lines and need to be tough negotiators. The Chinese have their bottom lines, their foreign policy negotiators are taking orders from the very top.

Akhilesh Upadhyay Upadhyay, former editor-in-chief of The Kathmandu Post, is a senior journalist who has written extensively on geopolitics.

Perspectives

18 min read

Nepal’s leaders should pay greater attention to developing coherent and effective policies for the northern border

Explainers

21 min read

We have not dealt with a disease like COVID-19 in over 100 years.

COVID19

Features

5 min read

Fraught relations within Nepal’s ruling party likely to cause delay in the entry of Covid vaccines when ready

Features

4 min read

The mountainous village of Tingla in Solukhumbu, with roughly 3,000 voters, boycotted the local and provincial elections of 2017...

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Perspectives

6 min read

The sporadic global events keep reminding us that the fate of these workers is prone to fragility the same as the country’s sources of foreign revenues.

Features

Longreads

36 min read

Filling a gap in the diplomatic history of Nepal from the Cold War days.

Opinions

6 min read

Angira’s death is one more example of brutality against Dalit bodies