Interviews

11 MIN READ

In an email interview with The Record, Nepali-Indian poet Rohan Chhetri expands on the ambitions of his poetry, his influences, and his use of the English language.

It is not often that a poetry collection like this comes along, so brimming with language, so vivid in its imagery, and so powerful in its evocation of times past, loves lost, and revolutions unrealized. Rohan Chhetri’s Lost, Hurt, or in Transit Beautiful is a singular collection from a poet who is part Greek rhapsode and part Nepali gaine.

Drawing heavily from classical Greek poetry, Chhetri, who is Nepali-Indian and hails from the Dooars region and did his schooling in Kalimpong, infuses the form with post-modern borrowings from a host of other cultures — Nepali, Indian, American, a Swede here, a Hungarian there, a Frenchman, a Canadian. The opening section is titled Katabasis, Greek for a descent into the underworld. The poem ‘Lamentation for a Failed Revolution’ borrows its structure from the Moiroloi, the ancient Greek tradition of lamentation. ‘The Indian Railway Canticle’ is, as its title suggests, a canticle, a hymn. In the hands of a lesser poet, any sense of personal style might have been lost under such a dizzying array of influence, but Chhetri is a new master. His poetry hearkens and beckons, it ebbs and flows, there is past and present, there is death and there is life.

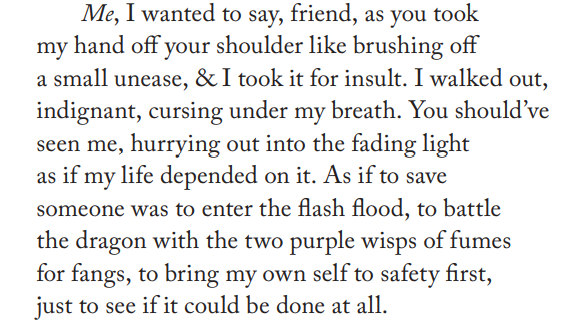

Consider this excerpt from one of my favorite poems in the collection, “New Delhi in Winter”:

Or this one from “Lamentation for a Failed Revolution”:

Chhetri’s themes are many — revolution in West Bengal, an elegy to an old friend now grown distant, the sweeping power of language to destroy and to rebuild, growing up and growing old. In Chhetri’s hands, they all come alive, effusing the senses with smoke, fog, blood, and lead.

Rohan Chhetri’s poems have appeared in The Paris Review, New England Review, and AGNI, among others. His latest book, Lost, Hurt, or in Transit Beautiful won the prestigious Kundiman Prize for Poetry and is currently available at major bookstores in Kathmandu and Pokhara.

If there is just one poetry collection you pick up this year, let it be this one.

What follows is an email interview with Chhetri where he expands on the ambitions of his poetry, his influences, and his use of the English language.

***

In an era of slam poetry and formless, pithy Instagram poetry, you've taken a very formal approach. The form of your poems in this collection appears to be both traditional and avant-garde at the same time. You draw primarily on Greek poetry but add flourishes of your own to drag that ancient form into the contemporary. As a Nepali-Indian poet, what is it about Greek poetry that speaks to you?

Thank you for that question, Pranaya, and for that observation. I think it is fair to say that, and my work can be read between the framework of formal “tradition” and what you here call the “avant-garde”. As a Nepali Indian poet writing in English from the academies of America — the most rapacious neo-colonial empire of the modern world — I think I’m wary of the variously learned disguises of style cultivated through the institution. To pitch my work towards an escape from this calcification of style is a baroque impulse which, I believe, is also a quintessential “immigrant” aesthetic. Perhaps an extension of the compulsion of always having to externalize oneself sublimated into art. In improvisation I couldn’t see myself, as one of the speakers from my book says. I embrace this, by which I mean I grapple with forms for the songs I want to sing — forms patched together from existing forms; the detritus of the vast mimetic echo chamber that is the American MFA industry; the cultural and poetic traditions and influences that are available to me, etc. Through a necessarily syncretic, (neo)baroque poetics, I’m interested in exhuming dormant traditions and stories and hauntings, and as a postcolonial poet, this proliferating impulse, this cross-cultural engagement with multiple traditions, is the only way of being a poet for me.

Hence, the formalism in the Lost, Hurt, or in Transit Beautiful too exists not on its own but in a relational tension to the formal violence to come, the fractures, the implosions where language itself — the English language and its formal poetic tradition — is in an uncertain relationship to the book’s subject. The “lamentation” and the Moiroloi, particularly, through the antiphonal mode, opened a formal space for me to stage the polyphony and the role of women in the long history of the Gorkhaland movement. The traditional antiphonal lamentation in Ancient Greek was performed by women who read out the names and accounts of the dead, answering a male poet who led the mourning lamenting the general devastation. I repurpose the roles a bit in my poem, where the role of the “professional” poet, one ensconced in the academy of a foreign country or in his couch at home, is nominal and faltering, where the women sing of the actual devastation and the song of their own resistance.

You've said in interviews that you also draw from “the Nepali poetic tradition”. Who are the Nepali poets you admire and what do you admire about them?

It would perhaps be overreaching for me to claim a conscious influence and engagement with the Nepali poetic tradition, something that I’m only now beginning to delve into as I translate Avinash Shrestha’s work and try to place him into the Nepali poetic tradition. When I first started writing, however, I believe I had in my head, and still do, echoes of stray poems by Devkota, Haribhakta Katuwal, Bhupi Sherchan, and many others we were made to memorize in school at St. Augustine’s in Kalimpong, alongside Keats and Wordsworth.

I’ve been engaging on and off on a little project I probably will never publish — a “writing-through”/adaptation of some of Ramayana’s episodes and Odyssey’s minor characters. I’ve also been looking at Jayaraj Acharya’s translation in a decent bilingual edition of Bhanubhakta’s Ramayan in English and the original, in conjunction with the Princeton Ramayana, and it is interesting to see Bhanubhakta’s elisions and the various cultural flavors he infuses to make the text his own. The adaptations I’m attempting are, of course, part of a larger trend of interventions on the epic, influenced by writers such as Pound, Hughes, Christopher Logue, and more recently Alice Oswald and the Indian poet Vivek Narayanan. But they also came out of encountering Pramithas, a super difficult text for me to get through, where Devkota, our greatest poet, marries Hindu and Greek mythology to create a truly syncretic and dense epic.

My engagement with the Nepali poetic tradition is hence more aspirational and something I hope to study and catch up to in the future. But, I suppose there are other dormant ways the rhythms of Nepali spoken language, music, and poetry persists in my work — from Jhalakman Gandarbha’s “Danfe Chari”, the sheer improvisatory and onomatopoeic genius of it; the melancholia of the persona of Narayan Gopal’s songs that draws a straight line to Devkota; and even Bipul Chettri’s music, particularly his first album and the beautiful new minimalist album Samaya which teases a particular Nepali melancholy so distinctive of life in Kalimpong and Darjeeling, while bringing together influences and references to early Dylan and Narayan Gopal so beautifully.

I’m writing, consciously and unconsciously, out of multiple cultural sites of influence. My work is a constant act of excavation, pushing up these dormant influences, while working with the various traditions that are available to me, making the poem-in-English a malleable, ragtag vessel.

Your influences, references, and acknowledgments are very diverse. Some, like Bergman, Camus, Bela Tarr, are quite overt while others less so. As with the Greeks, you appear to be reaching for a connection across time and space, across cultures. Is that accurate? Or do you hope to achieve something else entirely?

I guess that is fairly accurate. Apart from the “literary” tradition, we also have what Patti Smith calls a literary “bloodline” that is personal, non-linear, and draws from everywhere, which is, in my opinion, something to do with a deep, shared “temperament” with the artists and their works more than anything else. Ezra Pound talks of how all poets, living and dead, are contemporaneous to each other. I like that idea.

Nepali poetry has a rich history of political activism. Your poems too are very political. Do you see your poetry as a form of protest?

Yes, Nepali poetry has a rich tradition of being out in the streets, of being assimilated into slogans and speeches to great effect. I’m thinking of Bhupi Sherchan’s ‘Hallai Halla Ko Desh’. That kind of thing can be very powerful. Protest poetry, of course, has a long tradition in the Commonwealth. More and more, I’m interested in language, I think, how my politics can be made to bear on the language of the poem, in the linguistic and stylistic decisions, in the governing principle of the work. To tell you the truth, I do not see my poems particularly as a form of protest. As Brodsky said about fascism and evil, “Look at the language. It begins in the language”. I do believe, however, in imagination and language’s countering force, that if I use it with care and intent and precision, a different, quieter, kind of shift or change might transpire in someone’s shape of thought.

You often employ language as a site of contestation. You write in English, perhaps in an effort to appropriate the language and turn it against the colonizer. Would that be fair or are your motivations different?

I write in English because that was the language of instruction in school, the first language of my literary imagination. Of course, we also read Nepali as a second language in school. But yes, you grow up reading about Wordsworth’s ponderous musings in the Lake District in some bordertown in India. Perhaps a profound disconnect grows in a child’s imagination, who knows. So I suppose my poetry is in a way, as you hint at, trying to test these old forms and see how they hold up in the face of a post-colonial subject’s reality. What happens when I put in the tea garden of my hometown, a vestige of colonialism, for example, instead of daffodils; or a revolution, a flooding dam in the bordertown? In a sense, it is a kind of reinstatement of the land and its ethos and culture into the English poem and its formal traditions for a future reader. And yes, of course, using that very language and its forms to speak of the neocolonial ravages of the land and its ecology alongside the beauty and the lives of its people.

Following from my last question, if my characterization is right, how would you respond to Audre Lorde's “the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house”?

Lorde, in that essay, I believe, is talking of the need for intersectional feminism and representation, and the need to acknowledge differences within the monolithic category of “women” in the discussion of feminist theory. In this case, let’s run with that metaphor, say we’ve repurposed the master's tools and now fashioned it numerously out of our own materials. Further, we’re not looking particularly toward dismantling the master’s house — although a strategic dismantling is very much possible as we see in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! — as much as building new houses, excavating dormant ones, and creating new modes of relation by juxtaposing these now-various houses (which is to say traditions) alongside each other on an equitable power relation. It is also a way of changing and redefining and reevaluating our (power) relationship with what we call the centre/canon.

Finally, you're working on a translation of the Nepali-language poet Avinash Shrestha. What was it about his poetry that led you to attempt a translation? Why do you think he deserves a wider audience?

Something about the almost otherworldly aesthetic of Avinash Shrestha’s poems initially drew me to him. In the preface to his third book of poems, Anubhuti Yatra ma…, he talks of the “truths that exist outside of language” that cannot be accessed through the old “tracks” of a tradition that seeks to remain monolithic. He sums up his aesthetic project as a kind of grappling with this fugal sensibility, this poetic predisposition to wander outside of language to find something that “must ultimately be reined in language”. He does this by working in a mode pitched toward a repurposing of tradition, a home-grown surrealism, and a hybrid diction alternating between the high and the low. He talks of this mode as his way of bypassing “mannerism”, a term borrowed from art history denoting a highly affected literary style. This led me to read his work within the framework of an emerging “baroque” impulse, which evolves from the culmination and full expression of high mannerism. It was this that prompted the possibility of a critical engagement with his work and cinched my decision to translate him. The project will be a “Selected Poems” volume and I hope to finish it by the end of next year. I’m excited about what will happen to my own language (i.e., what can I make happen in the English language) on the other side of this project.

Pranaya Sjb Rana Pranaya SJB Rana is editor of The Record. He has worked for The Kathmandu Post and Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

9 min read

Akhilesh Upadhyay details all he has learned in his 30 years of journalism and offers advice to both aspiring journalists and experienced ones who are stagnating.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week, for Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson asked contributors what they enjoy most about writing. Here are their answers.

Perspectives

21 min read

Binod Bikram KC’s poems offer a sobering perspective on the times we live in

Perspectives

8 min read

In his article, Tim Gurung recollects his experiences moving to Hong Kong in the 90s and transitioning to a new life in business.

Writing journeys

19 min read

Buddhisagar, one of Nepal's finest novelists, recounts how Karnali Blues came to be and offers writing lessons on discipline, authenticity and style.

Writing journeys

14 min read

Raju Syangtan was once afraid of writing. Today, he is a celebrated poet and journalist. His story, on this week’s Writing Journey.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Social science researcher Sabin Ninglekhu provides prudent useful advice when it comes to academic writing, especially the longer kind, in this week’s Writing Journey.

Writing journeys

17 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson identifies 20 common mistakes Nepalis make in English and how to avoid them.