Writing journeys

12 MIN READ

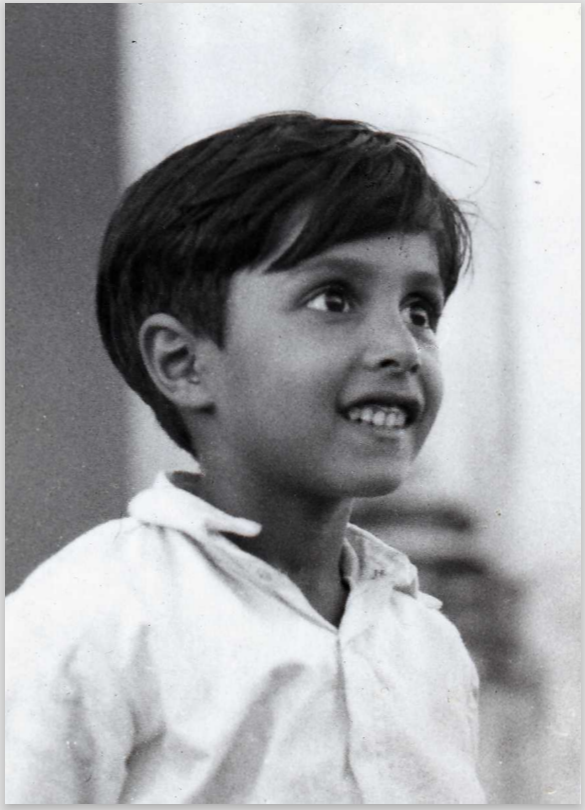

This week on Writing Journeys, engineer and political economist Dipak Gyawali pays tribute to the teachers who taught him to write precisely and meticulously.

My mood was sagging earlier this evening. Then I re-read Dipak Gyawali's wonderful Writing Journey and it picked me right up.

What I most like about his short essay is that it's about teachers -- a favorite mentor in graduate school in the US and the Jesuit fathers who taught him at St. Xavier's in Godavari, south of Kathmandu. Most writing journeys get launched and pushed along by a passionate teacher or two.

At St. Xavier's, Father Blanchard was “disorganization personified”, but his literature classes were “magic”. He taught Dipak to write by teaching him to read, to notice and appreciate well-chosen evocative words. In Fr. Blanchard's view, time never moved slowly, instead the “the hours moved like lazy cattle across a landscape”.

Dipak also shares a little of Father Watrin's magic: weekly paragraph writing, detailed logical outlining, and precis writing to root out “flabby verbosity”. Persistent practice, Dipak calls it. A love of new words but never to show off. After reading this, I hope never again to be conveyed home “in an intoxicated condition”. Fr. Watrin shows a much better way.

“Great writers, poets and artists of ages long past,” Dipak writes elsewhere in the essay, “speak to us today as if personally.” So too, it seems, do great teachers. Hats off to them.

Dipak knows how fortunate he was to study with such meticulous, paragraph-loving teachers. What a world might be possible if only every Nepali student could be lucky enough to learn good writing and critical thinking with similarly wonderful teachers.

Thanks to Dipak for sharing a little of his teachers' magic. In a later week I hope to share some of the magic of my own teachers.

Dipak Gyawali is a Moscow-trained hydroelectric power engineer and a UC Berkeley-educated political economist. Since the early 1990s, his research has focused on the interface between technology and society as related to water and energy issues. He writes a regular fortnightly column in Spotlight magazine and tweets from his handle @dipak_gyawali. He is co-editor of the book Water-Food-Energy Nexus: Power, Politics and Justice, from Routledge/EARTHSCAN (2019).

In Writing Journeys, every Wednesday, The Record highlights the thoughts and reflections of Nepali (and Nepal-based) authors and storytellers. We ask them what inspired them to pick up pen and paper in the first place and to share some of the research and writing techniques they have learned along the way. So far we’ve had Shradha Ghale, Kunda Dixit, Niranjan Kunwar, Kesang Tseten, Sujeev Shakya, Kalpana Jha, and Janak Raj Sapkota. I also describe Four ways to practice writing during lockdown

Next week: Manjushree Thapa

***

Writing to capture and share thoughts

I re-read classics every now and then, including a few years back, Tolstoy's War and Peace. Its opening chapter tells the story of a widowed countess fallen on hard times who wants her son appointed to an important position in the army at the start of the Napoleonic war, and is imploring a count close to the Tsar to use his influence to get it done. The count promises to do so, but Tolstoy writes, "He, like all worldly people, knew he would not because influence in society is capital, and if you gave it away to anyone asking for it, there would be none left when one needed it for oneself."

These lines leapt at me, as lines from good classics often do. Tolstoy's words could have been describing the ‘source-force, bhansun’ culture of any one of King Birendra's powerful secretaries or, for that matter, Girija Koirala's or Oli's!

Good writing is about both word-shaping skills and ideas. The former has to be learned as a craft but the latter comes from the intensity of inner reflections. It is the primary prelude to good writing: you must have something to say.

In the early 1980s, Kunda Dixit (of Nepali Times who was then features editor of The Rising Nepal), the well-known Nepali satirist Chatyang Master, and I used to bring out Shakti, the first Nepali energy magazine. We pushed Chatyang, who had never written a published piece in English, to write a piece for The Rising Nepal. When he did so -- a piece called ‘I am a Nepangrez’ -- Kunda said that he had to edit almost nothing. When you have something interesting to say, language is not a high barrier.

However, I don't want to downplay grammar, vocabulary, and other essential writing tools and skills. If you want to convey your pashyanti vak (your intuitive ideas, something from Hindu philosophy I describe briefly at the end of this essay) to others, it is essential that you do so in the standard way with little room for ambiguity or misunderstanding. This is where skills have to be learned the hard way, as a craft that becomes perfect with persistent practice.

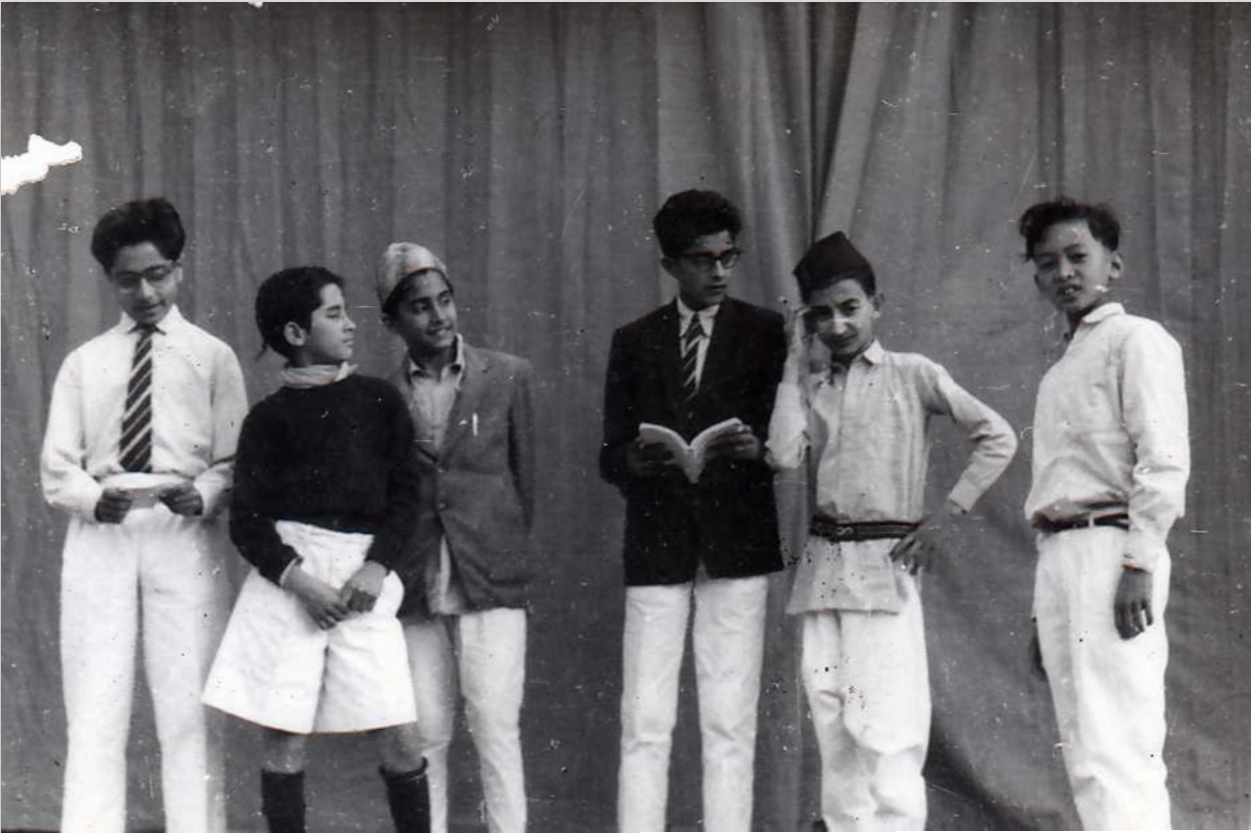

Some of us have been fortunate to have had great English teachers in St. Xavier's Godavari School who gave us that opportunity and guided us along the way. Three of my American Jesuit teachers stand out: Fr. Donnelly, Fr. Blanchard, and Fr. Watrin. Donnelly drilled us early in 7th standard with grammar, parsing, and punctuation; it was tough but with hindsight, most rewarding.

In the higher standards, Blanchard taught us English literature, including Shakespeare that was required for our Senior Cambridge exams. The exact opposite of Donnelly and Watrin, he was disorganization personified. Another teacher described him as the “delightfully most disorganized man I have ever met!” But his literature classes were magic; and it is to him that many of us owe our capacity to appreciate good literature and love brilliant expressions. It is still vivid in my memory, him telling us what a great difference it made to not say “time passed slowly” but to express it as, “the hours moved like lazy cattle across a landscape”.

It was Fr Watrin who honed our essay writing skills. It began with weekly paragraph writing assignments. The idea was that each paragraph should begin with a topic sentence followed by others that develop the thought to drive home the point. A paragraph should not follow another without a linking word or phrase to give logical continuity. To avoid flabby verbosity, we were also required to practice precis writing, summarize a big paragraph into a couple of sentences and still convey its gist.

Increasing our vocabulary was important, with us required to pick up a few new words every week; but big words for bigness’ sake were discouraged. I still remember him telling us how writing a sentence like ‘He was conveyed to his place of residence in an intoxicated condition’ was bad, and why it was much better to say, ‘He was carried home drunk!’ He also cautioned us not to write what was “pathetically obvious”, e.g., that ‘Nepal is a country between China and India’ or that ‘A cow is a four-footed animal’ which seems to dominate vernacular Nepali journalism.

Many years later, when on a Fulbright at UC Berkeley, my advisor Prof. John Holdren (who is now with the Kennedy School at Harvard and earlier was Obama's Chief Science Advisor) had his graduate students submit a paragraph of writing every week, just as Fr. Watrin did. The idea was that, if you could not express your idea in one simple paragraph of a memo, you would not be much of a success in your professional life. The submissions of my colleagues used to come back with Holdren's red marks all over, with comments almost as lengthy as the original paragraph itself. Mine, however, came back with just his signature and date. Disappointed, I remarked at the department's coffee machine that Holdren probably did not even read my pieces. That complaint seems to have reached Holdren’s ears via the department's secretary. My next piece came back with his comment: “Dipak, the reason I don't have much to comment on your writing is because you write far better than your US-born peers!” When I read that heart-warming compliment, I could only remember and thank Fr. Watrin!

When we moved on to essay writing, one of Fr. Watrin's iron rules was that no extra marks were given for correct grammar and spelling -- you were just expected to have them perfect -- but would face heavy point deductions for such mistakes. These days, with automatic spelling and grammar checks built into computer word processing programs, there is even less excuse for such mistakes. He also said that being able to understand and tell jokes in a particular language was the ultimate test of one's proficiency in that language. Hence, Jerome K. Jerome's Three Men in a Boat was required reading, and our school library had almost all of P.G. Wodehouse's books, which we devoured avidly.

But the most important habit inculcated in us by Fr. Watrin was writing detailed outlines. It had to be submitted together with our essays to demonstrate how much thinking and logical effort went into producing the essay. The more scratched up and dirtier the outline was, the better we were graded.

Many years later, I came across Edward de Bono's book Six Thinking Hats which I have modified for myself with four different color pens I use to prepare my essay outlines, including this one. I start with a black pen to jot down random points to cover; I then use a green pen for arrows and jottings to structure an outline of sequential arguments; I follow it with a red pen to be brutal with myself and cut out what is of lesser importance or even irrelevant, as much as I may like the point personally; and finally, a blue pen to run through with new thoughts, facts, and figures as well as the overall logical argument I am making.

Today, with computers (which should be nothing more than a glorified typewriter) I find colleagues and students sitting down to write in front of a blank screen without first going through the intellectual discipline of outlining and structuring their thoughts with pen and paper. Yes, computers make cutting and pasting much easier, but without a Watrin-type outline done in advance, what your reader will see is shoddy and poor logic, ambiguity, and repetition. It will only be humdrum vaikhari vak that will just not shine with intuitive truths you have glimpsed in the depths, even beyond pashyanti vak. That would be a lost opportunity for you and a punishment to your prospective readers.

Great writers, poets, and artists of ages long past speak to us today as if personally. How do they do it? We call their works 'classics' that outlive them and their age. Our own classical philosophies Samkhya, Vedanta, and Tantra describe expressed words (vak, meaning 'word' in Sanskrit but also a name of the Goddess of Wisdom Saraswati, Vak Devi) as vaikhari vak, or ‘coarse word spit out’. That happens only after truth transcendental, or para vak, is perceived as pashyanti (separated into subject and object) and passes through the polluting phase of madhyama vak (when mixed with emotions). Great writers seem to somehow bypass that polluting phase and bring eternal truths to us directly.

But it does not happen effortlessly. Tolstoy rewrote his War and Peace seven times and individual chapters as many as 21 times. For us lesser mortals, the detailed outline stage that Fr. Watrin emphasized is precisely where we should struggle for days on end, if necessary, before attempting a final writeup. Hopefully, we will then have successfully bypassed our inherent everyday humdrum biases to bring to our readers perceptions they can relate to across time and space. That reaching out to an unknown audience with ideas they might find thought-provoking and value greatly is a challenge worth aiming for.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

17 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson identifies 20 common mistakes Nepalis make in English and how to avoid them.

Interviews

11 min read

A 1963 interview with writer and critic Krishna Chandra Singh Pradhan

Writing journeys

12 min read

Ujjwal Prasai recounts his time growing up in Kakarbhitta and struggling with writing before coming to Kathmandu and establishing himself as a columnist and writer.

Books

Features

10 min read

Except for a few, most Nepali authors are compelled to pursue writing on the side while they work other jobs to make ends meet. But why is it so difficult to earn a living through writing?

Writing journeys

12 min read

Journalist Sonia Awale details how she got into science writing and journalism, and provides tips to budding writers in this week’s Writing Journey.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week in Writing Journeys, journalist and storyteller Chandrakishor writes about the value of learning new languages and using writing as a tool for social harmony.

Writing journeys

9 min read

Nepal’s preeminent sociologist, on this week’s Writing Journeys, offers insight into his academic journey, and asks students to read actively and question the text.

Writing journeys

11 min read

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.