Writing journeys

7 MIN READ

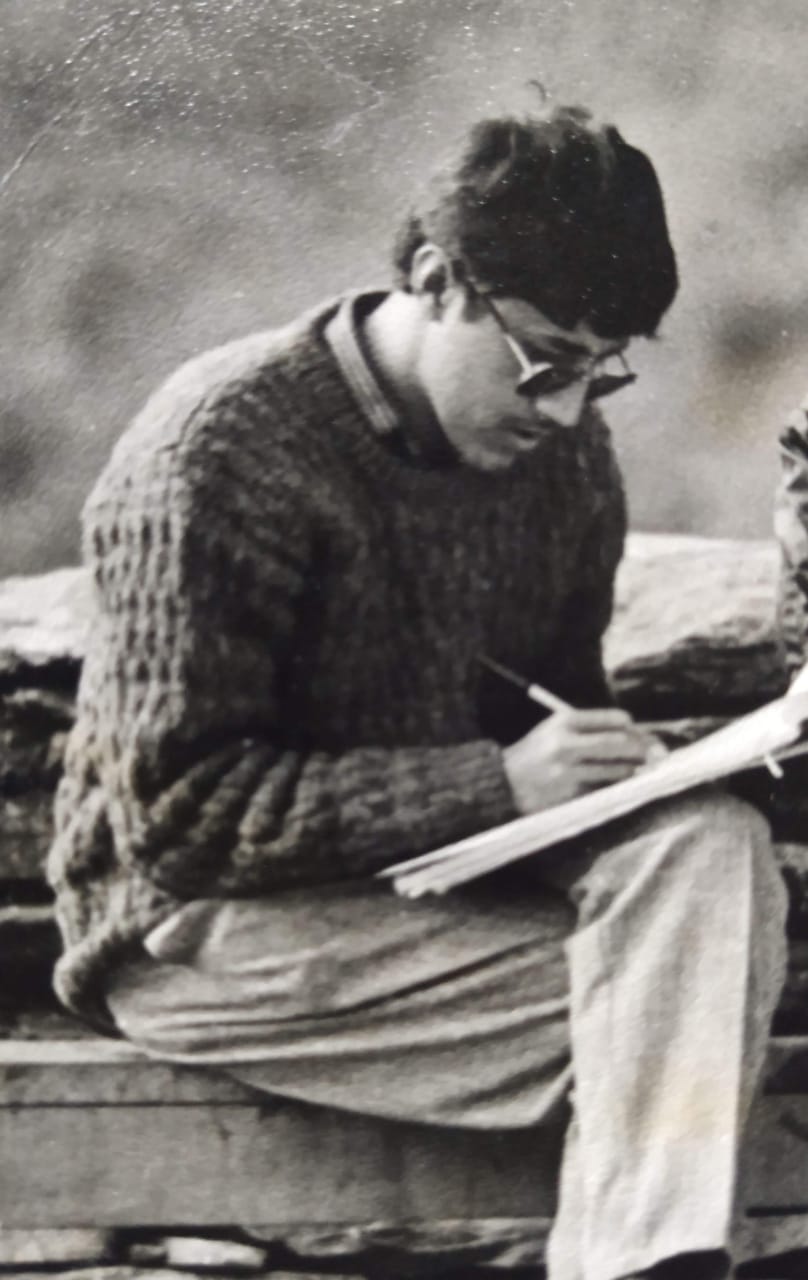

This week on Writing Journeys, the writer and consultant Sujeev Shakya talks about the importance of listening in writing.

When we think of writing, we often think of ‘born writers’ in a room by themselves chasing after creative genius.

But, as the Writing Journeys weekly series tries to show, we can learn from others’ tips and strategies that make for better writing. One of the most important of these, as several of our authors have already stressed, is that good writing requires being social, especially in the drafting process.

If you have met Sujeev Shakya, you know he gets energy from being around others. He can talk, yes, but he also is a good listener, an absorber of experiences and insights from others. His essay this week shows that his socialness is part of his secret: he grew up listening to stories; he surrounds himself with other storytellers; and he always finds key people to share a draft with. He reminds that creating good nonfiction is more than sitting in a room by yourself.

Besides that point, I like three other things about Sujeev's essay: learning about the writing culture of Kalimpong, his early emphasis on writing in Nepali, and his use of lists. I can always count on Sujeev for a good list. When working with professionals and PhDs on ways to improve their writing, I always point to Sujeev's essay ‘Change Begins at Home: The way the government functions is a reflection on Nepali society’, (The Kathmandu Post, August 2020), as a model of how to use a list to organize not just a paragraph but an entire essay. It's so straightforward, so clear. And don't miss that essay's artful conclusion as well.

Sujeev Shakya is the founder CEO of beed, an international management consulting and advisory firm. He writes regularly for The Kathmandu Post and is the author of Unleashing Nepal and Unleashing The Vajra.

Writing Journeys appears on The Record each Wednesday. In previous articles, Shradha Ghale reminds us that everyone is always still learning to write, Kunda Dixit stresses that writing is “not about showing off your vocabulary”, Niranjan Kunwar reveals that sometimes words “don't come easily”, and Kesang Tseten describes his process of “discovering the story” as he goes.

If you like to be surrounded by friends, you need to be a good storyteller and a good listener. I learnt this early in life. When you grow up with a mother tongue where most stories are passed orally generation to generation but get educated in English, you grow up with a hunger to listen to and tell stories orally, along with the urge to write them down.

Growing up in a Kalimpong home where the Newa language publication Dharmodaya was edited and published due to the ban in Nepal, the sense of secrecy and curiosity was immense. In school, my Nepali teacher Man Bahadur Pradhan used to say that Shakespeare can be found in the fields of the Himalayan hills, as our sense of poetry and prose was so immense. Nepali language was not mandatory, so many other students neglected it, but I wanted to pursue writing in Nepali. I started writing short stories and a Nepali novel. When my corporate career began, writing and communicating in English became my mainstay.

In the early nineties, because there were very few bilingual Nepali and English people in Nepal, especially people with computer skills (I was the first one to be provided a company laptop at Soaltee Hotel), the potential opened up for writing, translating, and summarizing. Since I spent a lot of time at libraries and read a lot, I could narrate many perspectives and did not take much time to write small pieces. From writing pieces for The Sunday Dispatch, interviewing Buddhist monks visiting Nepal for whom I was their Nepal Bhasa-English translator, my interest in writing grew. Also, a piece that I wrote for Der Spiegel made me realize that writing can also bring in much-needed extra bucks. Assisting in writing reports became an interesting way to get money for books and magazines.

I always had a different perspective on issues and questioned the status quo. I was strongly influenced by Jiddu Krishnamurti's insights: “The word is never the thing. The word prevents the actual perception of the thing or person because the word has many associations.”

For me, when I look back at my writing journey, I am grateful for three things. First, a great set of editors. Editors make the pieces come alive: it's like the Executive Chef who makes the final presentation of the dish prepared by sous chefs. Anagha Neelkanthan brought alive the ‘Arthabeed’ inside me. Ranjana Sengupta was my philosopher, editor, and guide for Unleashing Nepal and Unleashing The Vajra. The editing team at Nepalaya spruced up my Nepali writing. I always looked forward to the comments and reviews from my editors and others who reviewed the piece for me. Most importantly, I try to get the review done by someone from the target audience I am writing for.

Second, great influences. My uncle Jyoti Shakya was bedridden for 57 years but produced awesome writings. He wrote in Hindi for Dharmadut, a Buddhist magazine that was published from Banaras that inspired similar magazines in Nepal Bhasa and Nepali. He translated Buddhist Gyanmala bhajans from Nepal Bhasa to Nepali for a larger audience. He translated Buddhist literature written in Nepal Bhasa, originally translated from Burmese, into Nepali. I found the journey across languages fascinating.

Manjushree Thapa pushed me to go to an international publisher. I was introduced to Gurcharan Das, who not only agreed to guide me but also to introduce a Nepali author to the world. Over meals, coffee, and travel to literary festivals with the Pulitzer-winning author Kai Bird, I came to understand the expanse of the world of books. Through Namita Gokhale, I learnt how publishers, literary agents, publicists, and literary festivals all connect. At literary festivals, I thrived on nuggets of ideas, thoughts, and advice. Just being in the company of great writers gives me positive vibes. It's similar to the good feelings when in the same room with meditation masters.

Third, solid, careful research and reading. The internet has made access to information easy. It was so much easier to find citations for my second book than my first book a decade earlier. For nonfiction writers like me, the key is to get facts and the sources right. There are non-fiction books published in Nepal without a bibliography, where portions are just plagiarized. Like in professions where professional and ethical conduct matters greatly, writers are judged by the originality of the ideas, the facts they present, and the authenticity of the facts.

I find writing and cooking similar. You generally have the end in mind; it is that exciting process that brings about positive thoughts. A writer never plans to write a bad book, nor a cook a bland meal. In both cooking and writing, getting the right ingredients in the right process fetches you rewarding results. People talk about favorite books and meals for many years afterward. It is just about the joy!

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Writer and editor Rajendra Maharjan pens a powerful essay about his Writing Journey and the necessity of interrogating and changing oneself.

Books

5 min read

The book is a reminder that here are first-rate minds at work who can grapple with the “big questions” as well as anyone.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, US-based journalist and writer Sanjay Upadhya recounts his time working at The Rising Nepal under the Panchayat and the lessons he’s learned along the way.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, engineer and political economist Dipak Gyawali pays tribute to the teachers who taught him to write precisely and meticulously.

Writing journeys

13 min read

In this week’s Writing Journeys, Subhash Nepali describes how the Nepali education system failed him and how writing helped rectify that.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Ujjwal Prasai recounts his time growing up in Kakarbhitta and struggling with writing before coming to Kathmandu and establishing himself as a columnist and writer.

Books

9 min read

Three new translations, one into English and two into Nepali, provide new opportunities for engagement across languages, cultures, histories, and contexts.

Longreads

Features

34 min read

Chitwan National Park has earned international praise for its conservation successes, but it has also evicted indigeneous communities and upended many local livelihoods.