Features

8 MIN READ

Prem Pariyar’s advocacy has shed more light on caste-based discrimination in the US but back home, discrimination continues in Nepali universities and colleges.

Three years ago, when Deepa Nepali came to Kathmandu for the first time, she came with a lot of dreams. She was the first from her family to ever come to Kathmandu from Kailali, Sudurpaschim. She was also the first to pursue a Master's degree at Tribhuvan University.

"Coming to Kathmandu to study was a dream come true," said 28-year-old Nepali.

But living in this city of dreams was not what she had thought it would be.

"I was discriminated against for being a Dalit back in my village. But never had I imagined I would be discriminated against in Kathmandu, that too in a university, in the midst of such 'educated' people," said Nepali.

Nepali was able to secure a spot in the university's housing system, which charged nominal prices under the quota system for the underprivileged. "I come from a poor family and I had applied for the MEd program because of this housing provision so that I would not have to worry about paying for accommodation while I was studying," said Nepali.

But the warden of the hostel did not like Nepali's presence in the university. "She made my life miserable at the hostel, taunting me every chance she got for being a Dalit," said Nepali, who also is currently pursuing her LLB. “For missing two hostel meetings, she verbally abused me and threatened me, saying she would call in the student union people and drag me by the hair out of the hostel.”

It was not just the warden who treated Nepali as a lesser person. "Nobody spoke to me or came near me. In the mess, peers would treat the table I was eating at as untouchable," she said.

The discriminatory behavior became so much for Nepali to handle that she had to leave the hostel in less than a year, despite the system guaranteeing two years of accommodation.

What Nepali went through at Tribhuvan University, Nepal’s oldest and most prestigious university, is not an anomaly. It is the unfortunate experience of many Nepali Dalits who come to seek higher education at Nepal’s universities.

"My parents could not afford to send me to university or college so to continue my college education, I needed to work almost 12 hours a day. It was very difficult for me to focus on my education. Wherever I would go, people labeled me as Dalit. Even when I was discriminated against or called names and casteist slurs at my college in Nepal, I could not report it because the college did not have a place to report such incidents,” said Prem Pariyar, a rights activist who is leading the fight against caste-based discrimination in the United States. “As Dalits, we are forced to be resilient and put up with the discrimination. We are forced to become habituated.”

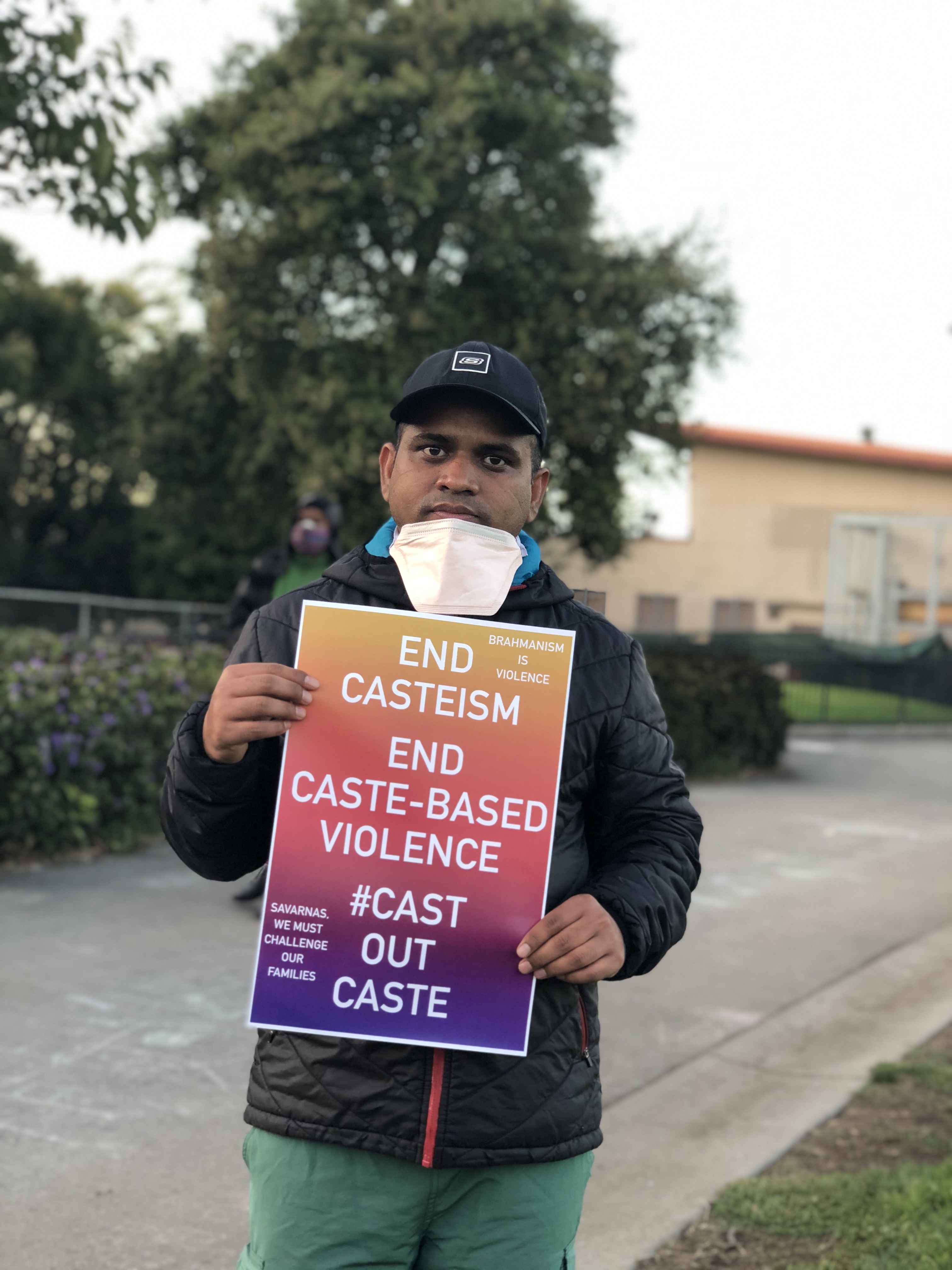

Pariyar has recently made headlines for his pioneering work in getting California State University, his alma mater, to add caste as a protected category in its non-discrimination policy. The fact that caste-based discrimination is now explicitly against the university’s policy, applicable in 23 of its campuses, is being seen as a small victory in the global fight against caste-based discrimination.

As Asian Hindus migrate to other parts of the world, they take the deeply entrenched caste system with them. In the US, this continued insistence on the caste hierarchy has exploded in Silicon Valley, where a large number of Indians work in the IT sector. A landmark case was filed in June 2020 by the California Department of Fair Housing and Employment against Cisco, a multinational technology conglomerate, and two of its senior engineering managers for discriminating against a Dalit employee.

A 2018 survey by Equality Labs of over 1,500 Dalits in the US found that 25 percent of Dalits surveyed had faced verbal or physical assault based on their caste; one in three Dalit students reported being discriminated against in education; two out of three Dalits reported being discriminated against at their workplace; 60 percent reported caste-based derogatory jokes or comments; and one out of every two Dalits reported living in fear of their caste being ‘outed’.

While increased reporting on caste issues in the US, along with Pariyar’s successful activism, has brought caste into the global mainstream consciousness, there hasn’t been a corresponding increase in scrutiny over discrimination in domestic institutions back home. Experiences like that of Nepali and Pariyar remain distressingly common in Nepal’s institutions of higher learning, a symptom of a disease that continues to afflict Nepali society as a whole.

Even after being forced to leave her hostel due to discrimination, Nepali had just as much trouble finding accommodation in the Kathmandu Valley. For three months, she looked for a new place to stay but as soon as people found her caste, they would turn her away. One such tenant was a Home Ministry employee, against whom Nepali is currently fighting a case at the Supreme Court.

"It's sad that we still live in a society where caste is above everything else. That a Dalit student has to spend more time visiting courtrooms and human rights organizations fighting for their dignity than be in a classroom, studying like the rest of her peers," said Nepali.

Her experience echoes that of Rupa Sunar, whose case made it to mainstream media in June 2021. Sunar was refused a room by Saraswati Pradhan on the grounds that Sunar was a Dalit. The incident received media attention for the debate that it engendered with many decrying Pradhan’s discriminatory behavior but others defending Pradhan’s right to rent to whoever she wants to.

Sunar and Nepali’s experiences both shed light on the numerous and far-reaching consequences of the Hindu caste system. Dalits are forced to seek out accommodations because a majority of Dalits are poor and do not own land and property in the capital city.

“Because most Dalits come from a low-income background – which is a fate foisted upon us by the upper caste rulers in this country – our immediate goals are to earn two meals a day. We cannot squeeze a revolution between two meals,” said Pariyar.

Becoming educated is often the only way for Dalits to move up on the social ladder but often, this lone opportunity too is denied. Due to their financial constraints, most Dalits require quotas and scholarships to pursue higher education. But as Pariyar points out, the selection committee for scholarships is often made up of dominant caste student leaders and administrators. These committees place an overwhelming emphasis on merit, ignoring the critical need of Dalits students, who are expected to avail of the ‘quota’ that they have been assigned. But even quotas are now increasingly coming under attack.

“What the Nepali education system does so efficiently is minimize our representation at school, university, or make the experience so awful that we come to resent it. The system is practically built to discourage Dalits from getting education,” said Pariyar.

Without access to education free of harassment and discrimination, Dalits will remain uneducated and unaware of their rights. It is a tried-and-tested formula, enacted first by the Ranas, to keep the marginalized and exploited forever in the dark. So in addition to the personal and individual experiences of caste, the system is also deeply structural. Even when Nepal’s schools and universities are not explicitly caste-based, there are implicit structural biases that deny opportunities for Dalits.

These less-visible forms of caste-based discrimination often crop up in conversations around merit and the necessity of quotas and reservations. Even among the young and educated, there is a pushback against quotas and an insistence on ‘merit’, without acknowledging the centuries of prejudice and inequity.

“Caste equity is today’s conversation. Dominant caste people often talk about why they deserve opportunities due to their “merit,” but never acknowledge the intergenerational systemic barriers that Dalit students face in fulfilling their potential from their childhood. Honesty matters – if we execute our existing policies honestly, we can make a huge difference but people are not honest which results in more systemic barriers for Dalit students,” said Pariyar.

Honesty, for Pariyar, is the minimum prerequisite. Honesty not only requires an open acknowledgment of inequities that continue to fester but also of the uncomfortable truth that many dominant caste individuals owe a large part of their success and accomplishments to their position in the caste hierarchy. In that regard, there is much that Nepali universities can learn from those in America.

“US universities are very serious about creating safe spaces for their students, staff, and faculties at their institutions. Nepali universities or colleges can learn a lot from the US universities to create safe spaces for their students. Caste oppressed students at their universities and colleges can start conversations about creating safer spaces,” said Pariyar. “But advocating for safe spaces and other Dalit-friendly policies can be daunting in itself because of the whole system stacked against them. It is in this fight that progressive students, staff, and faculties should come ahead and be their ally and fight for equal rights and justice.”

It is also important for dominant caste individuals to understand that anti-discrimination policies and quotas do not constitute ‘special’ treatment. They are, in fact, only a small step towards correcting centuries-long historical ills and making sure that Dalit students get to have the same academic experience as everyone else.

“If universities had policies that would protect students against caste-based discrimination then maybe Dalit students would be able to study like everyone else,” said Deepa Nepali.

Nepal might have a national anti-discrimination law but caste-based discrimination continues to persist, keeping Dalits out of school and away from higher education. More Dalits children are out of school than any other caste and even when they enter school, one-third of drop-out rate in primary and secondary education is attributed to Dalits; only about 4 percent of Dalits graduate to higher education, according to one study.

The movement to eliminate caste must first come with an acknowledgment of the continued persistence of caste accompanied by targeted interventions in the form of anti-discrimination policies, especially from institutions of higher learning like Tribhuvan University, the availability of scholarships and other forms of support for Dalit students, and the inclusion of Dalit representatives in decision-making bodies, including the ones that form policies.

“Not all Brahmins and dominant caste scholars and faculties are casteist; there are genuine supportive faculties who want a paradigm shift in how educational spaces should be,” said Pariyar. “I think it is important to work with them, educationists, and Dalit activists to carve out new policies and set/strengthen the foundations for an equitable Nepal.”

Pranaya Sjb Rana Pranaya SJB Rana is editor of The Record. He has worked for The Kathmandu Post and Nepali Times.

Marissa Taylor Marissa Taylor is Assistant Editor of The Record. Previously, she worked for The Kathmandu Post. She mostly writes on the environment, biodiversity conservation and public health.

Features

13 min read

For the victims of war-era atrocities to whom Nepal has continually shown an unwillingness to deliver justice, a bleak future awaits

Interviews

5 min read

Saraswoti Nepali, recipient of this year’s Darnal Award, in conversation with Gyanu Adhikari

COVID19

Perspectives

7 min read

In Nepal, and other parts of the world, domestic workers are routinely denied social and labor protection, and with Covid-19, their problems have only gotten worse.

Opinions

6 min read

The upper-caste resistance to the term ‘dalit’ shows a refusal to let go of long-standing Hindu caste-based hierarchy

Features

10 min read

Disillusioned with current politics, young people are now leading a seemingly futile call for the reestablishment of the monarchy

Interviews

Longreads

Features

44 min read

As the crisis unfolds in Myanmar, two Burmese youths talk about their experiences and what life is currently like on the ground there.

The Wire

Photo Essays

5 min read

In the absence of local elections, school boards have become an increasingly important way to exercise control, especially over foreign aid

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter