Perspectives

Longreads

47 MIN READ

Sam Cowan returns with fresh insights on the drafting of the Nepal's 1959 constitution, the subsequent general election, and a new witness to King Mahendra's coup d'état.

This is a follow-on to “The maharaja and the monarch”, my long article on King Mahendra, published on April 21 2015. This new article is in four parts. The first three cover what is, for me at least, new information on the drafting of the 1959 constitution and the precise role of Sir Ivor Jennings; how funds from the same overseas source were channelled to two very different men to cover expenses prior to the 1959 election; and a perspective from a new source on the coup which King Mahendra launched on December 15, 1960. The fourth part is based on a 1962 British Foreign Office file, FO 371/166568. It is innocuously labelled “Internal political situation,” but contains impeccably sourced information which more than justifies the title given to this article.

In my 2015 article, I wrote:

“Sir Ivor Jennings, a leading constitutional authority from the United Kingdom, was brought in to guide a five-man committee of officials and politicians on how to prepare a constitution that would balance the demands of Mahendra to have a continuing influential role and the demands of the parliamentary government to make the popular will, democratically expressed, decisive. The 1959 Constitution in some crucial areas was not as written or as advised by Sir Ivor Jennings. A note from the British ambassador states that Mahendra rewrote parts of it himself to strengthen the position of the monarchy. It is a safe assumption that this information came from Sir Ivor Jennings.”

This was BP Koirala’s view on Jennings’s contribution:

“Then we had to decide who was to write the Constitution. I relaxed when it was suggested that Sir Ivor Jennings would draft the Constitution. I told the king that the person who had drafted Ceylon’s constitution would surely not give us a document that would help finish off democratic rights. I told the king: “I will accept the Constitution if he drafts it.”

The king then formed a constitution drafting committee, with Surya Prasad, Hora Prasad and others on it. But the royal palace rejected the draft handed in by Ivor Jennings. He gave them another draft, which too was cast aside, the argument being that it gave too much power to the legislature. An exasperated Jennings submitted a third draft and said: “I will not submit another draft. I am leaving.” [Page 182, Atmabrittanta: Late Life Recollections, trans. Kanak Mani Dixit]

BP Koirala was wrong, though understandably so, and particularly on one key point. During the early meetings of the committee other members objected, not because Jennings proposed to give too much power to the legislature, but that he proposed to give too much power to the king. Koirala could not have appreciated that the Jennings who wrote the Ceylon constitution in 1946 had a completely different mind-set to the man who was called on to help draft Nepal’s new constitution in 1959.

After Sri Lanka, and because of the outbreak of the Cold War, Jennings’s views reflected:

“…the Cold War imperative of delivering political stability and regime continuity to ‘Third World’ countries and countering the ‘threat’ posed by the Soviet bloc rather than a political commitment to promote constitutional democracy worldwide. In this respect, Jennings’s constitutional work in South Asia built on his experiences in the region in an incremental way and reflected his view that law and politics are inextricably intertwined…

... On Nepal, Jennings’s mandate from the FO was clear: produce a constitution strengthening political stability in Nepal. The design of the constitution was based on Jennings’s reading of Nepal’s socio-political situation after the revolution of 1951 rather than the principles he argued underpinned a functioning constitutional democracy like in Britain. He identified the Shah Hindu monarchy as Nepal’s only stable political institution and drafted the new document around the King. Jennings’s official mandate was to craft a document within the framework of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy. However, in line with the importance he had articulated in his scholarly work of placing constitutional structures within local political contexts and his Cold War political expediency, Jennings’s constitution established a framework completely tilted in favour of the ‘hereditary executive’ element of government, the monarchy, with a very limited scope for the ‘representative executive’.”

The above two extracts come from an article by Dr Mara Malagodi,“Ivor Jennings's Constitutional Legacy beyond the Occidental-Oriental Divide”. [footnote] Journal of Law and Society, vol. 42, number 1, March 2015, pp. 102-26.[/footnote]

The exact changes which Mahendra made to Jennings’s draft are set out in another excellent essay by Dr Malagodi, “Constitution Drafting as Cold War Realpolitik: Sir Ivor Jennings and Nepal’s 1959 Constitution.”

In this article I can only give a summary of some of its many insightful and revealing details. The paper’s scope is well set out in the opening lines: “The paper explores the appointment, work, and legacy of the noted British constitutionalist Sir Ivor Jennings (1903-1965) as constitutional advisor to the Nepal Government in the late 1950s. Jennings visited Kathmandu for one month from 28 March to 24 April 1958. He was employed by the British Foreign Office (FO) upon the request of the Nepali monarch, King Mahendra Bikram Shah, to advise the small Commission charged with the drafting of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal 1959 – the third constitutional document in the country’s history.”

The essay makes clear that although the UK government was very keen for Jennings to accept the invitation from Nepal, and was covering his pay and expenses, the King and his advisers were also very keen to enlist him.

Jennings arrived in Nepal on 28 March 1958 and submitted a rough draft on 3 April. It was later typed and returned to him for corrections on 7 April. During the afternoon of 7 April, Jennings had an audience with King Mahendra, who had not yet received a copy of the draft. On 11 April, Jennings met with the Commission for the third time to discuss his draft; the main point of contention was the extensive powers granted to the King. Two days later he again met with the Commission and put forward a number of arrangements to strengthen the constitutional position of the king. By 15 April, Jennings had prepared the second constitutional draft which he deemed satisfactory. On 19 April, the Commission met without him and, on 20 April, Jennings completed the third draft. On 21 April, Jennings met again with the Commission and the drafting of an Explanatory Memorandum was agreed, which Jennings prepared that day. The members of the Commission were keen for him to submit it under his name, “as an expert”. On 23 April, Jennings held the sixth and final meeting with the Commission to finalise the draft and the Memorandum. He left Kathmandu the following day. There is no indication that he left in a huff as suggested by B.P. Koirala.

In his Confidential Notes to the FO, Jennings explained the reasons for this insistence on the centrality of the Shah monarchy in his design. He commented that the meaning of drafting a ‘democratic constitution’ in Nepal was to prepare a document, “designed to vest power in a middle class, usually English-speaking oligarchy which was to pay attention to the needs of the oi polloi because they have the vote [...] but the difficulty in Nepal was to find the oligarchy”. Thus, Malagodi writes, in the light of the Cold War context, Jennings was instructed to devise a constitutional framework capable of delivering political stability in the strategically located Himalayan Kingdom. As a result, the design of Nepal’s new constitution was based on Jennings’ reading of the country’s political situation, and he identified the Shah monarchy as the only stable political element and institution in Nepal.

He noted, however, three main problems in this respect: first, King Mahendra was popular, but “obstinate and lacking character”—and he was devoid of a court party he could rely on. Second, there was an unofficial Indian influence against the monarchy, mostly channelled through the Nepal Congress, whose politicians he unceremoniously described as “lesser [Indian] Congress wallahs”. Third, Jennings felt that it was crucial to separate the person of the King from the institution of the Crown: “one must not presume too much of the King’s personal popularity and make him too obviously responsible for the efficiency of government. Whatever happens, the Government is going to be pretty inefficient and (I suspect) corrupt”.

The draft Constitution was first approved by the coalition cabinet and then submitted to King Mahendra for promulgation. He chose to sit on it for eight months before promulgating it just one week before the scheduled general elections, on 12 February 1959, leaving the political parties contesting the elections in the dark about the powers and functions of the government they were hoping to form.

Malagodi had access to Jennings’s private papers and was able to compare his third draft with the constitution that was finally promulgated. She writes:

“A perusal of Jennings’ third draft reveals that substantive additions were made to the text, most likely by the King and his entourage, especially with regard to the ethnocultural elements of the document, after his departure from Kathmandu. In particular, the clauses pertaining to the Shah monarchy were expanded to include extensive cultural, religious, and historical references supporting the King. A constitutional ban on conversion was inserted under Article 5, Freedom of Religion, for the first time in Nepali constitutional history. However, the framework devised by Jennings in his drafts regarding the efficient part of the Constitution with a central role of the Crown was preserved intact in the promulgated version of the dispensation.”

The final section of the paper headed, “The 1959 Constitution and Jennings’ Legacy in Nepal,” starts with this important paragraph:

“The 1959 Constitution has been a landmark document in Nepal’s constitutional history for two reasons: first, from a substantive point of view, it entrenched the dominance of an unaccountable executive under a nominally democratic framework. Second, from a symbolic point of view, it gave prominence to the historical ethnocultural nationalist narratives legitimising the wide powers of the King: the historical dynastic continuity of the Shah monarchy as the symbol of the unity of the nation, Hinduism, and the Nepali language. A perusal of Jennings’ three constitutional drafts in the archival material demonstrates that no ethnocultural references were included in the constitutional text during his visit. It is logical to infer that the Nepali Drafting Commission, possibly under more or less direct instructions from King Mahendra, inserted that constellation of ‘symbolic’ provisions into the final document after Jennings’ departure. However, Jennings was implicated with the symbolic dimension of the new Constitution. It was the substantive institutional choices of a constitutional framework tilted in favour the monarchy that allowed for the symbolic ethno-cultural elements to find a place in the constitutional text, even if at a later stage”.

Thus, from the king’s point of view, Jennings did a perfect job. His draft put the monarchy as dominant in the new Constitution and left the way open for Mahendra and his officials to legitimise this centrality in ethnocultural nationalist terms. In the Preamble, it clearly stated that the Constitution was granted as an, “exercise of the sovereign powers of the Kingdom of Nepal and prerogatives vesting in US in accordance with the traditions and customs of our country and which devolved on US from Our August and Respected forefathers.” This was explicitly confirmed in a later section: “…the executive power of Nepal is vested in His Majesty, extends to the execution and maintenance of this constitution and the laws of Nepal, and shall be exercised by him either directly or through ministers or other officers, subordinate to him….”

In the Preamble, ‘the people’ were still paternalistically treated as ‘subjects’ rather than as rights-bearing ‘citizens’. Conspicuously absent was any reference to the establishment of a democratic system which had featured prominently as the avowed goal of all successive governments since King Tribhuwan’s historic proclamation of February 18, 1951.

Ample powers were given to the King to suspend Cabinet Government under Article 55 or even the Constitution under Article 56, and to assume direct powers under Article 77, the power to remove difficulties. Crucially, the monarch’s power was backed by the Constitution giving the King exclusive control over the Royal Nepal Army under Article 64.

Mara Malagodi concludes her essay with these lines:

“The 1959 Constitution can be interpreted as the progenitor of the 1962 Panchayat Constitution in light of the substantive and symbolic centrality accorded to the monarchy in both dispensations. Thus, if the contiguity between the two Constitutions is accepted, it can be argued that they saw Nepal through the Cold War. From this perspective, then perhaps Sir Ivor Jennings did help Nepal secure political stability, but certainly at the expense of constitutional democracy.”

Viewed now from an historical perspective, responding to UK’s geo-political requirements rather than the rights, or needs or wishes of the people of Nepal was a high price to pay.

Duane R Clarridge is a former CIA officer. In his book, A Spy For All Seasons: My Life In the CIA, he describes work in his first appointment as one of the earliest CIA officers stationed in the US embassy in Kathmandu. He arrived with his wife and family in January 1958. He was well-informed about Nepal before arriving in the country and quickly built up a wide range of contacts. Preparations for the 1959 general election attracted his attention and this extract is worth passing on:

“From my point of view, Koirala was far and away the best choice for Prime Minister in the upcoming elections. He had good support from the people and was an effective leader. The king’s game seemed to be to play off the parties against one another; hoping to end up with a fragmented parliament that would let him rule as before. What the Indians were up to I never did fathom for sure. One could conclude that they would have supported the Nepali Congress Party on ideological and fraternal grounds; however, they seemed to have considered Koirala too independent of mind and therefore supported the king. The British came at it from a different and more “imperial” angle: they arranged to provide the Crown Prince with a young Englishman as tutor and then bundled him off to Eton. The Nepali Communist Party was financed by its Indian counterpart, which may in turn have been the recipient of Soviet largess. By this time, I was rather well plugged in to the principal political parties, including those of the enigmatic Dr K.I. Singh, who seemed to be playing closely with the king.”

It was widely believed in Nepal that the king had indeed allowed the elections to go ahead in the belief that there would be a hung parliament and that he himself would continue in effective control of the administration. BP Koirala believed this was also the Indian assessment, and that India used this as an argument to persuade the king to hold elections. [footnote] See, People, Politics & Ideology: Democracy and Social Change in Nepal, Hoftun, Raeper, and Whelpton, p.60, footnote 61[/footnote] Clarridge goes on to explain that by the early spring of 1959, Koirala had become worried about Nepali Congress’s ability to win a majority in the elections as, “the king’s activities were not ineffectual.” In early March 1959, Koirala signalled that he needed to meet Clarridge urgently in Koirala’s home. Both men agreed that that there was mounting uncertainty about the Congress Party’s ability to win a majority in the election. Koirala asked Clarridge, “to consider means to bolster the Nepali democratic process as embodied in the elections”.

It is clear that Koirala asked for money and, as we shall see, he got it. But, to get permission to write a book about his time in the CIA, I suspect that Clarridge had to agree to avoid saying explicitly that the US was covertly supplying cash to influence the results of Nepal’s first democratic election; hence the need to refer to it allusively.

Clarridge agreed to help. He sent a cable to Washington asking for “benign support” to the Congress Party. He outlined the current political situation, the problems the Congress Party was encountering and the machinations of the king. He concluded that the US should prefer a clear-cut Congress Party victory to ensure stability and a solid start at building democratic institutions in the country. His CIA boss in Delhi and the US ambassador there, Ellsworth Bunker, separately supported his submission. A week later he had a secret cable from “the legendary director of central intelligence [DCI] himself, Allen Dulles”, that his request had been approved. Clarridge writes that, “A courier was dispatched from New Delhi. Koirala was pleased and my relationship with him was strengthened and broadened; he became even more frank with me about intra-Nepal Congress matters and his tactics for the election. About six weeks later, Koirala came to see me with additional thoughts on electoral problems. They seemed reasonable, and I made the case to New Delhi and Headquarters. Again I received approval.”

Another key player was soon to seek “benign support”. With increased Chinese activity in Tibet, the US started to take a greater interest in the elections in Nepal. This resulted in Ambassador Bunker visiting Kathmandu more regularly. He met with a number of the more senior politicians but he always saw King Mahendra. On one of these visits, the king let it be known that he, too, wanted some “electoral assistance”. Bunker thought it prudent to comply and Washington agreed.

What happened next is best given verbatim:

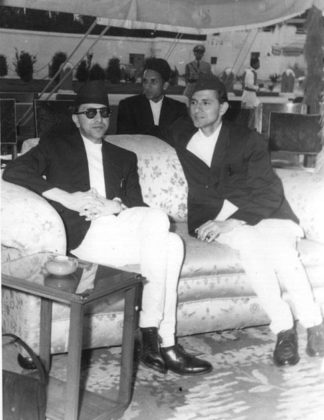

“I requested an audience with the king through General Thapa, the king’s military aide and my chief contact at the Royal Palace. At the appointed hour, late in the evening, the king stepped into the parlor of a small cottagelike structure beside the palace, which he used for informal audiences, where I was already ensconced. We sat down and made a modicum of small talk. The room was extremely dim, lit by one tiny lamp with an opaque shade. Even the king could only get forty watts of power out of a hundred-watt bulb. Electricity in Nepal came from a hydroelectric generator plant, and in summer before the arrival of the monsoon rains, there was very little water to drive the turbines so power was particularly weak.

King Mahendra, as was his custom, day or night, wore sunglasses. He was clearly uncomfortable. Realizing that further attempts at conversation would only embarrass us both, I put an envelope on the small table between us. The king made no effort to pick it up. I said good-bye and left.”

The 1959 elections started on February 18 and were completed by April 3. The last result was declared on May 10. Instead of a hung parliament, the outcome of the election was a sweeping victory for the Nepali Congress party, which won 74 of the 109 seats. As its leader, BP Koirala was asked to lead, in the first instance, an interim government, and took office as prime minister on May 27. Finally, the new constitution was brought into force on June 17 and King Mahendra opened Parliament on July 24 that year.

One can only speculate on how the US-supplied dollars were spent and how they may have influenced the outcome. However, given the results, one is left wondering whether King Mahendra thought he had got poor value from the parties he had supported with the CIA-gifted cash? Assuming, that is, the money finished up in party coffers.

After the elections, but before parliament had met for the first time, BP Koirala and an aide paid a late night call on Clarridge. They were carrying a small suitcase. The visitors were clearly upset. Koirala explained that he had received information from a reliable contact at the palace that the king intended to arrest, if not kill, him and the leadership of his party, and return the country to autocratic rule. Inside the suitcase were two British Sten submachine guns and ammunition. Clarridge observed that both appeared to have spent quite a lot of time in the ground. Koirala explained that the weapons were for his protection and he asked for more to protect his party’s leadership. Clarridge consulted Washington and received the answer he expected: the US did not want to get involved.

Later, at a reception to commemorate the first meeting of the new parliament, Clarridge met BP Koirala. They shook hands and the prime minister quietly murmured some words of appreciation. They never met again.

Mr. President of the Confederation,

By chance I found myself in Kathmandu on December 15, the day of King Mahendra’s coup d'état. This statement is not an exaggeration, since the sovereign, making use of Article 55 of the Constitution, suspended almost all the Constitution, arrested all the Ministers of the Koirala Cabinet, the presidents of the Chambers, the heads of ministries, and the leaders of all the parties, and took over, with the support of the army, the direction of the country as a true dictator.

These are the opening lines of a diplomatic dispatch to Bern from the Swiss ambassador to New Delhi, Jacques-Albert Cuttat, dated December 20 1960. (My translation; the original French is available here.)

Cuttat also covered Nepal and paid regular visits to Kathmandu. His dispatch records the end of the short life of Nepal’s third Constitution, and is worth perusal. Thirty-six days after returning from a state visit to the United Kingdom, King Mahendra launched a coup d'état which had been planned before he left for the UK, and which ultimately gave him absolute authority over the entire machinery of government. All those listed were indeed arrested and it was quickly apparent that Mahendra planned no mere change of government. In typical style, many consultations took place and confusing statements were issued, but there was never any doubt about the end point: the restoration of the monarch’s absolute authority.

The dispatch continues:

I had been in Kathmandu for four days when the coup d'état occurred. It seems to me appropriate to summarize the discussions I had during this period with Mr Koirala, some of his ministers, my colleagues in the Diplomatic Corps and other observers. First, because it gives a better understanding of the scope of the regime change; and, second, because the King seems determined to continue the policy of the government internationally, and in economic matters; and, last but not least, because everything suggests that Mr Koirala and his Congress Party (that is to say socialist) will return to power one day or another thanks to a counter-revolution.

The Ambassador went on to pay this fine tribute to BP Koirala’s statesmanship:

On my first visit to Nepal, I met Mr Koirala in his capacity as Prime Minister and Minster in charge of Foreign Affairs. This friendly, intelligent, very popular statesman, formed politically in India in the atmosphere of Mr Nehru's party, was quick to mark his independence from certain aspects of the international policy of the Prime Minister of India. He told me that, “between the non-alignment of Pandit Nehru and that of Nepal, there is this difference. Mr Nehru, in disputes between East and West, is still slightly inclined to balance to the side of the communist countries while Nepal strives to remain strictly neutral.” During the events in Hungary and Suez, India spoke "with emotion" against the Anglo-French intervention in Egypt, but did not condemn the Russian occupation of Hungary. Nepal, on the other hand, was perfectly equitable, and unlike India who favoured Lumumba, Nepal voted in favour of the admission of President Kasa-Vubu's delegation. Mr Koirala does not approve of the advances that Mr Nehru believes he must make to the Soviets for "strategic" reasons to counter the Chinese threat. In his opinion, "every international event must be judged according to its own merits". Nepali politics, he said, is closer to Swiss neutrality than to the non-alignment of India. Neutrality in peacetime does not seem to him to be contradictory as claimed by Mr Krishna Menon; on the contrary, he would like the neutrality of Nepal to become permanent like ours, but he knows that this implies “a long period of learning.”

Two days later, that is, on the eve of the coup, Mr Koirala, referring to his domestic policy, did not hide how difficult it is for him to convince the reactionary circles of the country of the urgency of the land reform measures (or, more exactly, of the tax system) that were passed in Parliament last summer. I will come back to this point, which played a key role in the events of December 15th.

Mr Koirala's views on foreign policy were confirmed by the Deputy Prime Minister [Subarna Shumsher] (who seems closer to the King than Mr Koirala) and by the Minister of the Interior.[SP Upadhyaya] The latter noted that strong language is the only one that is effective towards the governments of totalitarian countries. During his recent visit to China, he was concerned at how much the regimes of rural and urban communes transformed men into automata.

Cuttat passed on the British ambassador’s high words of praise for BP Koirala as PM:

The British Ambassador, who has been in Nepal for four years, has summarized the political situation in Nepal as follows. Like Afghanistan and Burma, Nepal has confidence in the effectiveness of neutrality. The country, never a colony, its neutrality, unlike that of India, bears no resentment against the West. Koirala deems Nepal to be indefensible militarily, which is why he has done nothing to improve or increase the small Nepalese army of about 12,000 men. A mixture of optimism, insensibility and idleness makes the Nepali rulers relaxed and even reckless when considering the serious menace coming from the north.

If the Chinese continue to support and implement the principles of “ethnic propriety” and “administrative control”, the northern populations (Bhotias and Sherpas) will be gradually integrated into the Tibetan region because they are culturally and racially more Tibetan than Nepalese, and are not under Kathmandu’s control. This danger is heightened by the fact that trade between Nepal and Tibet (exchange of Tibetan wool and salt for Nepali rice) is gradually being reduced to zero. As for Koirala, my English colleague holds him in high esteem: "I am proud he told me of our Prime Minister.”

At this stage of the Cold War, both the UK and US had deep seated concerns, amounting to paranoia, that Nepal was not doing enough to combat “the serious menace from the north.” Very few practical or constructive suggestions were ever offered. Do not get too close to China, would be the summation of the many thousands of words written on the subject. But did they have to worry so much? The postscript to my article, “Prisoners of War” provides ample proof that King Mahendra and his Chief of Police needed no lessons from anyone on the need to be alert to China’s actions and intentions in Nepal. Of course, it often suited the monarch’s intentions to pretend otherwise.

The warm endorsement by the British Ambassador of being “proud of our prime minister” reflects what was written in the political brief passed to London before King Mahendra’s UK visit. It stated: “the government has shown a welcome determination to tackle the difficult problems with which they are faced in trying to create a modern system of administration and to bring about social and economic reforms in an extremely backward country. There is little doubt that this Government represents Nepal’s best hope for the future.”

Within a few months, these high words of praise were forgotten as Britain quickly adjusted to giving total support to an autocratic monarch who quickly established a political system that give him absolute power. By February 12 1962, the same ambassador was writing, in a Minute headed “The Situation in Nepal” (FO 371/166568): “The wisdom and necessity of the king’s actions will long remain open to argument but I hold that it was based on the king’s sense of responsibility for his country’s welfare and not on lust for power. There is a strong fundamental argument against government by the interplay of political parties in a country unable to muster enough talent to form one adequate cabinet, let alone an alternative administration.”

The dispatch contrasted the attitude of India with other international actors:

In the opinion of the Ambassador of India in Kathmandu, Mr Dayal ,(brother to Mr Hammerskjoeld's representative in the Congo), Nepal is governed by outdated customs and even primitive laws (imprisonment on information of the abandonment of Hinduism, the national religion). This country, he told me, is a conglomeration of tribes and valleys rather than a nation: it is unfriendly and ungrateful to India because of its lack of political maturity and its inferiority complex.

Mr Dayal's disdain for Nepal contrasts with the benevolent sympathy of my American and British colleagues. The European experts, established in Nepal for several years, and in particular our compatriots (very attached to this country), feel that India is observing its small back neighbour (twice as large as Switzerland: 8.4 million inhabitants), with the same imperialist and colonialist attitude that she has so often criticized England for, and for which she fought so hard in the rest of Asia and Africa. According to them, India would have done everything, especially at a time when its representatives were still the official advisers of the King (i.e. until the May elections, 1959) to hinder the economic development of the country, by maintaining an important formal mission in Kathmandu; by, for example, refusing to allow experts to be sent to Nepal and by declaring that there are enough doctors in the country! India would monopolize Nepal's exports by imposing a 30% transit fee and by increasing the amounts of bickering.

Indian officials today are rightly going to find these words very uncomfortable but, without excusing them in the least, they need to be put in the context of the times. India’s dominance over Nepal’s affairs in the 1950s is hardly a matter of dispute. The same can be said of the willingness of Nepal’s rulers to accede to India’s demands. In Nepal: Strategy for Survival, Leo Rose puts this point in an appropriately stark way: “New Delhi’s concept of Nepal’s interests was accepted almost automatically in Kathmandu, at least at the official level. Indeed, it is probable that some Nepali leaders tended to be over-responsive in this respect, interpreting even casual suggestions by the Indians as advice to be acted on . . . On a number of occasions, the Nepal government not only tamely followed New Delhi’s guidance but actually took the initiative in seeking it. That the Indians began to take Kathmandu too much for granted and tended to act in a rather cavalier and condescending fashion with regard to their own prerogatives, is therefore hardly surprising.” (p.195)

Cuttat reported on American perceptions:

Here are some more remarks from the charge d'affaires from the United States, which I thought were well informed. In his opinion, Mr Koirala would, perhaps out of vanity, have been somewhat taken in by the Chinese game of being conciliatory, even generous, towards Nepal in the demarcation of the Nepalese-Tibet border; a simple tactic to isolate lndia by making her look as the only uncompromising neighbour. The excuses that Chou-En-lai presented to Nepal for the Nepalese soldier killed in the Mustang area by Chinese troops, in particular, would have given Mr. Koirala the impression that he had succeeded where Nehru had failed. He would neglect a little too much the police and the army, convinced that China, for fear of a war with India, will not risk an invasion into northern Nepal. My American colleague added that his country, because of its financial difficulties, would not be able to provide Nepal with substantial military assistance; if Nepal asked, the United States does not favor the entry of Nepal into SEATO because of its geographical distance from the other member countries of this military organization.

I would contend that what is asserted in the first part of the above paragraph is an unfair and unjustified piece of speculation. (Much more information is available in my long article on, “The curious case of the Mustang incident.”)

The remark about Koirala neglecting “a little too much” the army and the police reflects US and British paranoia at the time that Nepal was not doing enough to protect itself against a Chinese attack. Self-evidently, a small increase in numerical strength of the army was not going to ease such concerns.

Cuttat speculated on personal animosity between monarch and prime minister as a factor:

Such is the background to the coup d'état of December 15, which surprised the whole world. Only the British ambassador was in the capital; the 4 other Ambassadors - USA, USSR, China and India - were away; the first three had just taken leave and Mr. Dayal went on a tiger hunt with General Thimayya [the Indian Army chief of staff who was in Nepal on a week’s visit] on the morning of December 15! The King and Mr. Koirala had dinner together at Mr. Dayal’s on the evening of the 14th. I saw Mr. Koirala and some of his ministers on December 13th and did not sense the least concern. The only indication of anything abnormal is the unusual speed with which the presentation of my Letters of Credence and my protocol visits were organized. In short, the King and some military confidants were able to maintain secrecy until, on the 15th of December at 1 o'clock, they arrested at the same time nearly all the political personalities of the country.

These are held in military buildings or residences of the royal family. The success of this work is all the more surprising since no one was aware of the animosity of the King towards his Prime Minister and his socialist policies. King Mahendra had mentioned it several times to Mr. Nehru who, however, never hid his sympathy for the Koirala government (after the coup, he publicly declared the new regime as “very unfortunate” and “a step back from democracy”). It seems that Mr. Koirala and his associates felt reasonably secure in the saddle so did not take seriously the hostility of this shy king and his entourage with their out-of-date ideas.

The evidence on ‘personal animosity’ is mixed. KP Bhattarai, a close colleague of Koirala, believed that there was, and this was a key factor, but Koirala himself quoted many occasions when Mahendra went out of his way to treat him with the utmost courtesy and to speak very highly of him. Here are his own words from Atmatbrittanta: “The king had mixed feelings of love and hate towards me, I think…..He definitely became concerned upon seeing the extent of my popularity among the people, how I worked as prime minister, and the very momentum of events. But that was also at a time when he began to speak in praise of me…..The king was impressed when he saw my work ethic, by the debates I used to have with him, the discussions we used to have in trying to establish some principles of governance, and my ambitions.” (p.197)

Cuttat cast doubt on Mahendra’s publicly proclaimed reasons for launching the coup:

In the proclamation of December 15th, the King goes so far as to accuse the entire Cabinet as, “totally unable to maintain order in the country, of being irresponsible, of being anti-national, corrupt and retrogressive”. These accusations seem to prepare the ground for trials of high treason, and are all the more shocking as they make one think of the parable of the beam and the mote. [footnote] Cuttat is referring to a powerful condemnation of hypocrisy in The New Testament: “Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again. And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother's eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye? Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye? Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother's eye.” Matthew 7:1-5, The King James Version Bible [/footnote] All my informants assured me that under the Koirala regime corruption was tending to decrease and that the economy and the democratic institutions of Nepal were finally moving slowly forward. We must therefore seek another motive for the sudden manoeuvre of the King.

The deep tentacles of corruption in Nepal are well described in this extract from Joshi and Rose: “Corruption as an issue in Nepali politics is of such a complex sociopsychological nature that it will be misleading to equate it with its literal meaning. If corruption denotes distribution of favours by persons in power, then it was the political way of life in Nepal long before democratic experimentation was introduced in 1951. The Rana administration was then nothing more than a colossal network of corruption practised for the benefit of a particular family and at the expense of the people.” (p. 321)

On progress in tackling endemic corruption, this quote from the 1959 Annual Report from the British embassy is worth repeating for its prescience and its reminder of the scale of the problems which faced the Koirala-led government: “The new government has not yet shaken off the long established customs of graft and nepotism, the Public Service Commission is still ineffective and the Civil Service is woefully inadequate to translate the administrative measures of Parliament into executive action. Much will depend on the personality of the Prime Minster who in the last eight years has matured from the idealist but volatile revolutionary into a man of able and sound judgement, and upon his relations with the King who still holds powers of dissolution.”

The US ambassador, Henry E Stibbens, had seen Mahendra on December 9, prior to going on leave, and the king had assured him that nothing would happen in his absence. That added a sharp edge to their next meeting on December 21. The ambassador reported that Mahendra said that “he had planned this move for some time and knew of the approximate timing when the Ambassador last saw him on December 9.” The king told him that “he took the step on his own responsibility with no outside influence whatsoever brought to bear,” and that, “he dismissed the Government and imprisoned its leaders because they were guilty of corruption and aiding and abetting communism.” In his dispatch that gave an account of this meeting, Stibbens gave Mahendra’s explanation the short shrift it deserved. He wrote, “In analyzing this coup d’état, for this is what we believe it to be, we feel that the King’s motives in taking the precipitate action he did were guided less by the issues of corruption and Communism than by a growing fear that his own personal position and prestige were dwindling and that if he did not act soon, it might be too late . . . the real motive behind the move was the preservation of the monarchy and the Shah dynasty in its absolute form.”

Cuttat speculated on “the main factor” which prompted the monarch to act:

The main factor appears to be the so-called law of “land reform” adopted by the Parliament last summer. This term, reminiscent of expropriations, in reality refers to the following two measures: the abolition of “birtas” and the institution of a tax system.”Birtas" refer to properties that the kings of the last century had exempted from property tax for the benefit of generals who had rendered them service. The title holders of these properties collected the rents, and this was hereditary and with the right of transfer. The abolition of this privilege has earned the Koirala government the unanimous opposition of all their beneficiaries; that is to say, not only the entourage of the king and the Ranas, but also of a large number of small rentiers living on incomes from these “birtas” legitimately acquired. It was imprudent, even unfair, not to compensate them. As for the tax system, which did not exist until last summer, it introduced a property tax of 7 Indian rupees per ropani (1/13th of an acre). This Tax is an indispensable minimum for financing public expenditure. In their carefree way, however, the Nepalese people are looking forward to the new regime when they will be exempt from this tax, even if it has to be paid for by foreign aid. The king has thus earned for himself a popularity of a demagogic and very fragile nature, because he will not be able to avoid – if he remains in power – restoring this tax in one way or another. In this respect, the Koirala government, far from deserving reproach, has shown courage and elementary common sense.

The imposition of a tax on birta holdings was a factor, but it was not the main one. It is much more likely that the protests and demonstrations against the measure by the groups mentioned simply provided Mahendra with the excuse or cover he needed to launch his coup. In their book Democratic Innovations in Nepal, Joshi and Rose, produce strong evidence for asserting that “it is doubtful that King Mahendra’s deep seated aversion to political parties and party politics would long permit him to play a purely constitutional role, as designated in the 1959 Constitution.” [pp 384-88]

Cuttat reported suggestions that Koirala’s actions and behaviour contributed to his downfall:

The main criticism which can be levelled at Koirala in this case is a failure to secure the support of the king and the army. The Ambassador of the United States confided in me that Koirala never took his advice to indicate publicly, from time to time, a modicum of sympathy for the king. Instead, he made fun of him in public. He was paying punctually civilian salaries and delaying the payment of army pay. A little more caution might have been sufficient to maintain the previous regime that suited the country so well. The coup d'état, in fact, compromises internal stability and slows down economic and political progress of this “pre-medieval” country where 88% of transport is done by man.

Given what we know now, it is hard to see what Koirala could have done to secure the support of the king and the army. The constitution gave Mahendra total and absolute control over the army. The high caste-dominated officer corps of the day would have despised both Koirala and the concept of parliamentary democracy he represented. They knew that Mahendra was their one and only boss, and from the outset he cultivated them with favours. It is also hard to see why the king would need publicly expressed sympathy from the prime minister, given how the constitution—which he had directed personally—left him with a wide range of executive authority. There is no source known to me of Koirala withholding army pay or of him making fun of Mahendra in public. Either action would have been tantamount to giving the king every excuse to act as he eventually did. As their period in office rolled on, Koirala and his team became increasingly concerned that Mahendra would move against them at some stage and they were wary of giving him any excuse to justify his action.

Having studied many sources covering this period of the history of Nepal, I believe that Mahendra acted as he did primarily because of the reasons highlighted earlier by US Ambassador Stibben and by Joshi and Rose: the preservation of the monarchy and the Shah dynasty in its absolute form and a deep seated aversion to political parties and party politics. In addition, at a basic temperamental level, King Mahendra deeply disliked not being in sole charge. One small indication of this is that in the first 11 months of 1960, leading up to the date of the coup, Mahendra was absent from Nepal for over five months, including three-and-a-half months spent consecutively in Japan and the US, and a month-long stay in the UK. So there was not much time for building up brotherly respect.

Cuttat gave his views on what might happen next:

What will happen in the immediate future? Will the King succeed in setting up his new Council of State now that almost all the capable men of the country are detained? Without doubt he will seek the support of some members of the deposed government. The United States Ambassador thinks that he might execute a few of them. But, he added, he has a tiger by the tail; if he doesn't succeed in getting the cooperation of former ministers and other political leaders, he exposes himself to a hostile reaction from that part of the population (there are already reports of unrest in a town in the south-east) and from most foreign countries; if he releases them, he opens the door to a counter-revolution. His great mistake is to have taken this irrevocable step. The throne he tried to save on the 15th of December is now more threatened than ever.

The Nepalese Communists, who have 4 members out of 109 in the lower house, will not fail to exploit the situation. The king may only make things worse in this respect by cracking down on them mercilessly. “All Nepalese communists and all communist agents are or will be arrested,” the provisional foreign secretary told me.

From the point of view of domestic policy, the future looks pretty grim. However, this does not preclude foreign experts, especially the SHAG Swiss team, from being optimistic about their technical assistance. The king, in fact, informed them that he intended to support and even to extend their tasks and implement new projects. His aim is to ensure the continuing generosity of the many Eastern and Western governments that provide Nepal with financial and technical assistance. As for international policy, my colleagues and other observers do not plan any important change.

Accept, Sir, the President of the Confederation, the assurance of my highest consideration.

So, as they would do now, the donors continued with their aid donations despite having deep reservations about the actions taken. Nor were there any public words of censure. Reading through the annual reports written by successive British ambassadors during the 1960s, there is barely a word for the incarcerated BP Koirala, and of sympathy none: concerns about what was seen as Nepal not doing enough to combat growing Chinese influence and the future of Gurkha recruiting appeared to be all that mattered.

In my 2015 article, “The maharaja and the monarch”, I wrote:

“Reacting to reports of the first closure of newspapers in Kathmandu, on February 10, 1961, a British Foreign Office official wrote: “the King is finding that to maintain power in his own hands, more and more repressive measures are necessary. There is seemingly no end to the process. The fact that the liberty of the press is being restricted shows that the King is becoming uncertain of his position, an ominous sign that he may have bitten off more than he can chew.” As events unfolded during 1961 and 1962, this looked to be an accurate assessment, but the official, like everyone else, could not have predicted China’s invasion of India on October 20, 1962, coming to the rescue of an increasingly fearful Mahendra. Evidence from a Foreign Office file in the National Archives, from sources very close to him, indicates that he had mounting concerns about his personal safety and the survival of his Panchayat system. That is a story for another day.”

That day is now!

There was remarkably little public reaction to the overthrow of a government elected by such a large majority just 18 months prior to the coup. Ten weeks later on February 26, 1961, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip arrived in Nepal for a four-day state visit which was rated as a great success. The security situation started to change in the autumn of 1961 when attacks were mounted against government installations across the country by a Congress guerrilla army. The decision to initiate an armed campaign was taken by Subarna Shamsher who had been Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister under BP Koirala. He had been on a private visit to Calcutta and was the one minister to escape arrest. He was at first reluctant to support armed action but was persuaded to do so by others, including by India’s Prime Minster, Jawaharlal Nehru. [footnote] A History of Nepal”, John Whelpton, p. 99.[/footnote]

This extract from the British Ambassador’s Annual Report for 1962 sets the scene well:

“The border incidents continued without intermission until early November. The raids, organised on Indian territory by Nepalese exiles, usually had police or customs posts as their objectives. The intruders seized what arms they could, and retreated to Indian territory. No part of the long frontier with India seemed inviolable, and penetrations were especially deep in the Ilam area, adjacent to Darjeeling. The raiders were successful partly because of the almost total lack of road communications inside Nepal which made it impossible for reinforcements of army or police units to be moved quickly to a threatened spot, and partly because their retreat seemed always to be assured by the indifference of, or, as the Nepalese maintained, the connivance and cooperation of the Indian authorities. The Indian government consistently rejected Nepalese charges of connivance, and maintained that the raiders originated on Nepalese territory and were expressing the demand of the Nepalese people for a return to a democratic system of government. The Indian view gained wide acceptance abroad largely because the press overseas obtained its reports from Indian correspondents.”

This last point is well illustrated by this selection of newspaper headlines, culled from a 1962 British Foreign Office file, FO 371/166568, labelled, “Internal political situation”

On January 22 1962, in Janakpur, during a royal tour of the Eastern Tarai, as Congress guerrilla attacks were becoming more widespread, a home-made bomb was thrown at a vehicle in which Mahendra was travelling. The king was not injured and his tour continued uninterrupted. Papers in FO 371/166568 cast doubt over the publicly stated reason for the king being in the area at this time.

The extract above is from a minute in the file. It was signed by O. Kemp, a foreign office official and dated 23 Jan 1962 [not the filing date stamped on top visible in the image above]. News about the bomb thrown at Mahendra’s vehicle in Janakpur on the same day did not reach London until early the next day. The Mr Stonor mentioned had been a tutor to the Crown Prince in Kathmandu before he attended Eton College. He is referred to in an extract I gave earlier from the Clarridge book. He became a close friend of the Crown Prince and had obviously met Birendra on his return to London after the Christmas school holidays when this information was passed on. I am confident that what is reported is accurate and came from the Crown Prince.

Not surprisingly, this was followed by a note, dated January 24 1962, from a senior Foreign Office official, Mr FA Warner, to the Foreign Secretary and other Ministers, which began by saying, “This is a warning minute to say that I think we may be in for serious trouble in Nepal.” The third paragraph read:

“The King is experiencing difficulty in maintaining his authority and an attempt was made on his life yesterday. The Crown Prince, who has just returned from holidays in Nepal, says that the King is daily expecting a coup. Apart from this the astrologers have predicted very serious earthquakes on January 26 or February 3. The last time they did this was in 1921; they were right, and thousands of people perished. On this occasion nobody wants to run any risks, and the population is leaving the cities or shoring up their houses. The king is afraid that his opponents will take advantage of this state of panic to launch their rebellion. He has left Kathmandu and proposes to remain in the countryside protected by a small force of his personal bodyguard.”

As it turned out, there was no earthquake, or any sign of a revolt, but King Mahendra was not freed of concerns. The cross-border raids continued as did the deterioration of his public image abroad, thanks to the energic activities of Congress propagandists. Mahendra could do little about the raids but, unusually for a Shah monarch at the time, he decided to play his personal part in countering the bad PR. The result was a large half-page spread in a popular and populist UK newspaper, the Sunday Express. The journalist Herbert Chapman was well-known at the time

The headline speaks for itself, as does the opening lines of the text. It is worth reproducing an excerpt here:

“We talked, first, about democracy, which he had suspended in Nepal.

‘I am very democratic-minded myself,’ he said, ‘and if I can lead the nation in the proper way for the time being the people will soon be able to make their own choice in a true democracy.’

‘You can see for yourself that our country is very underdeveloped. All our energies must go towards building up Nepal. There is no room for political bickering – which is why I have banned political activities.’

‘For the last 10 years we have not been able to apply democracy in a proper way to develop the country. This was because of two things. First, the mass of the people were illiterate – only 2% could read and write in 1950 – and could not understand the democratic choice.’

‘Second, the handful of leaders who did understand politics were working for the own benefit rather than for the good of the country.’

The king told me, ‘There is no political unrest except that coming across the border from India. I cannot say whether India is merely closing her eyes to that activity or are also supporting it. But at government level, relations between our two countries are still friendly, and we hope they will remain so.’

We were camped in the Tarai Plains district along the Indian frontier in an area in which extremists of the banned Nepali Congress Party have recently attacked police posts and engaged in sabotage.

I suggested that India was disturbed over Nepal’s agreement with the Chinese that permits construction of a road that will run from the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, to Kathmandu. India fears that this road pointing straight at the heart of India, could carry Chinese tanks.

Said Mahendra, ‘I do not understand the great importance attached to this road. There already are some 50 trails used by traders between Nepal and Tibet, using yaks and ponies or on foot. One of these is to be widened to take vehicles. One road will not make that much difference, although naturally, as communications improve, our friendly ties with China will be strengthened.’

‘I wonder myself how the people dare to say we are turning towards communism. We are a monarchy and believe in God. China is Communist and anti-religious. China offered to help build the north-south road and I saw no reason not to accept. Nepal needs many things and we will accept aid from any friendly country so long as there are no strings attached.’”

There is no record of the impact of this personal PR effort but there is clear evidence, from mid-1962 on, as guerrilla raids increased in intensity, and a long armed struggle looked more and more likely, that Mahendra began to think about the need for a compromise. His worries intensified towards the end of September 1962 when India imposed an unofficial economic blockade. Emissaries, including the British ambassador, were sent to talk to the imprisoned BP Koirala. It is appropriate to leave the final words on the collapse of the armed revolt to this “friendly, intelligent and popular statesman”:

“I remember the day the British ambassador came. It was monsoon time, and the sun was just coming out after some rain. Because it was the hot season, I was wearing only pyjamas and a vest. After that, in October, the Chinese attacked India. Jawaharlalji apparently said, these Chinese are in a very bad mood. There is no saying what they will do. For this reason you must stop your armed action.” When he said that, Subarnaji and the others suspended the action and later called it off altogether.

“There was a significant event during my jail term. A minister from that period, perhaps it was Rishikesh Shah, told me later in Benares that the king was greatly disturbed, the commander-in-chief had told the king, “Your Majesty must seek a political solution, because the military option alone will not work. Our army has engagements on many fronts, and if they open another one it will be very difficult for us.”

The king called a meeting of his council of ministers, where he said, “I will release BP Koirala, and develop an understanding with him.” There were two who opposed that suggestion, Tulsi Giri and Biswabandhu, who said, “Please give us a few days, a fortnight.” The Chinese invasion happened immediately after that, at which point the whole thing became moot … In jail, we resumed our despondent life behind bars.” (Atmabrittanta, p. 276)

The Chinese invasion saved the monarch’s imposed Panchayat system and his absolute position within it, but in the longer term the monarchy in Nepal was to pay a high price, as the Swiss ambassador Jacques-Albert Cuttat foresaw in his dispatch. I argued in “The maharaja and the monarch”, that with the clarity of hindsight, one can see that his coup d'état on December 15 1960 started the long process that led to the end of the Shah monarchy in Nepal. Mahendra’s inability to see that preservation of the lineage lay in accommodating the monarchy to a constitutional position, which, for all its inadequacies, was sketched out in the 1959 Constitution, set the monarchy on a precipitous road. His choice of preserving the monarchy and the Shah dynasty in its absolute form was ultimately unsustainable in the modern world, short of Nepal reverting to a despotic military state, as in the Rana era. The 1990 Constitution, again for all its inadequacies and ambiguities, gave the monarchy another chance to move to a purely constitutional basis, but King Gyanendra rejected it by his unconstitutional actions that started in October 2002 and ended by his assumption of absolute power on February 1 2005.

Based on a one-hour private conversation I had with King Gyanendra in Narayanhiti Palace in November 2002, I can say that he was motivated by a desire to emulate his immediate predecessors by granting his people a constitution that would restore his father’s Panchayat system in a modern form and give him a central role in decision-making. Beyond this aspiration he had no plan worthy of the name, nor had he the people with the talent to implement an appropriate plan even if there had been one. From an early stage, it was clear to all disinterested observers that, in the circumstances of the time, his move was bound to end in disaster for the monarchy.

:::

Sam Cowan Sam Cowan is a retired British general who knows Nepal well through his British Gurkha connections and extensive trekking in the country over many years.

Perspectives

5 min read

By acting consistently in favor of democracy and the rule of law, Nepal’s Supreme Court has fulfilled its function of defining the limits of acceptable political action and the consequences of legal subterfuge.

Features

5 min read

Will Dahal continue the infighting within the NCP, or will he completely sever ties with Oli? It all depends on the other head honchos’ moves

Explainers

8 min read

The week in politics: what happened, what does it mean, why does it matter.

The Wire

Features

16 min read

11 have been sentenced to life in prison while the Tharu community in Tikapur continues to pay the price for the horrors of 2015

Features

5 min read

The ruling party’s top leaders have finally come to a truce, but the peace probably won’t last

Podcast

Longreads

Perspectives

22 min read

Throughout Nepali history, the brutality of the caste system has stunted social transformation

Features

5 min read

A report by Amnesty International highlights the dire state of foreign domestic workers in Qatar

Explainers

3 min read

Changes that the proposed bill will have on civil service