Books

9 MIN READ

Many of the poems in Itisha Giri’s new collection are dedicated to women, talk about women, and diagnose how women occupy the pages but have not been allowed to occupy similar spaces in society.

archive n. a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place, institution, or group of people

This is a review of An Archive.

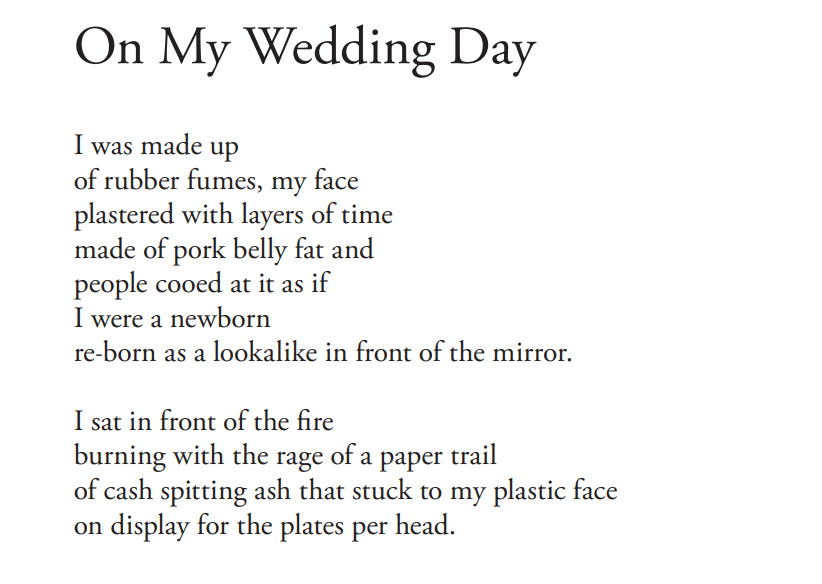

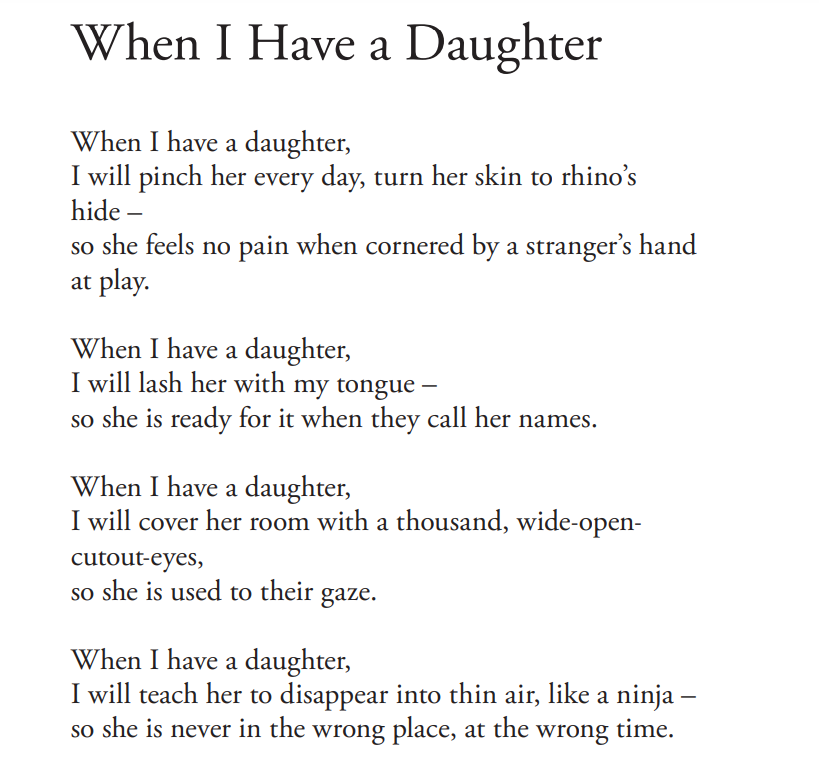

There’s defiance in the way Itisha Giri’s An Archive begins. The poems in this slim collection cannot be categorized into one poetic form — they oscillate from free verse to blank verse, from meterless phrases to rhyming lines, from short stanzas to long verses. Some pieces are satirical and some a narrative. There is even a crossword puzzle devoid of any clues; there are lists, a classified advert, and a few pop-up message boxes.

The poems in Giri’s collection demand the reader’s attention. The book seems to want its owners, its borrowers, its ephemeral holders to invest their time in it. It refuses to be just an accessory you skim through while a generic Netflix show plays in the background, always one episode away from asking, ‘Are you still watching?’.

This book, an “archive of consonants”, asks the readers to agree to its personal terms and conditions before turning the page. In a way, it is similar to the ‘I’m not a robot’ box that we often come across on the internet, something that has become a marker of our humanity, that we alone can decipher patterns and recognize pictures. This book too presents illustrations — a girl with an umbrella at a bus stop, a garland of marigolds, a snail’s shell and across it, a snake’s head — alongside its poetry. But it also demands that the reader go further and acknowledge the humanity behind these pictures — the futility of carrying an umbrella under a gray and rainless sky, the garland of marigolds severed by a clinical slice of the knife, or the pale yellow of the snail’s shell in sharp contrast to the brightness of the fruit of the lemon tree. A pair of robotic eyes would fail to see the remnants of an earthquake-bound kitchen, or a pen and a pencil trying to find their way to their owner so that they could write and rename and perhaps erase some of the alphabets from this archive of consonants.

An Archive takes ordinary objects from a mundane human life and produces stories that are so evocative and powerful that it doesn’t take long for these objects to become extraordinary. Whether it is a government office, or a plain polyester towel, a gifted kitchen set, a busy road, or a lengthy to-do list, Giri pours life into each inanimate object. The government office is simultaneously a place where one looks for someone but also a barren space, populated only by “orifices and headless objects”. There is apprehension with the ordinary — narrow pavements are punctured with potholes, four-wheel drives emit fumes, or zebra crossings demand a hop and a skip — all things that could incapacitate someone or end their lives.

It is death that often rears its head in An Archive, to such an extent that one wonders whether the book is actually an elegy. This motif evokes other women writers — Parijat, who relates a bed to a tomb and writes about dying before death, and Banira Giri, who talks about walking boldly over corpses. Shades of both writers are evident in Giri’s poetry.

Death permeates the book, and for the readers, there is no looking away. In the poems, death begins with a small brush, an insinuation of the texture of an old person’s skin:

I gently pinch her skin and make it stand and then I witness the slow death, the slow collapse

Death, then, becomes an omnipresent figure, and so the broken garland of marigolds atop a pictureless frame makes another appearance:

At his wake,

I am told I must measure his worth

…

I am told to build a house for him

…

What they don’t know is

he already has a home,

his slippers are at the door,

the cricket is on and his plate is still warm.

And when it finally happens — when death finally occurs — there is the chaos of assuaging the spirits and then after a while… nothing. Only silence.

On days you refused to eat

I had to watch you

in silence, I had to

wait for you

to resurface

I asked you to hang in there,

to keep floating —

head above the water,

but I never asked you if you could swim.

Death is mundane; it is inevitable and thus, it exists everywhere. In zebra crossings that the writer doesn’t care for, and under tires that are made from “hair, skin, nails, and asphalt”, and during wars where human shields are “mascots of a fragile peace”. Death surrounds us, it is inside us, and we have no option but to succumb to it:

“His blood report showed traces of dejection, and high levels of betrayal and hate.”

The poems in An Archive are not just metaphysical though. They also draw from the contemporary, the social and the political — the pandemic that now seems like part of an extended family, the ambiguity of language, mothers and daughters, and men who have “ultraviolet hands”.

The most powerful stories in this book emerge from women who subsist on “borrowed money and borrowed time”, and take on the dual destiny of being both “creators” and pigs up for “sale” or “slaughter”. The pages in the book that are dedicated to women, that talk about women, diagnose how women occupy the pages but have not been allowed to occupy similar spaces in society. Despite being “easy to spot”, they are invisible. Despite crying out loud, women’s words are reduced to whispers and lies, not to be believed, only to be swept away, unheard.

Stories emerge from instances that we hear on the news — an accusation of sexual assault against a famous celebrity — or perhaps see in our neighborhood or experience inside our homes. Instances that we assume to have been archived already and yet continue to persist in a vicious circle that keeps repeating itself. And so, there are also hints of hopelessness in the writer’s words — even some indecisiveness, some numbness.

The book provides no conclusion, no clean end to a proverbial story. It leaves us with questions, so that the reader has no option but to come back to it and revive the book in its second life. In a way, there is defiance even in the way the book ends — refusing to become a commodity to be stored on dusty bookshelves or thrown into cluttered drawers. It asks to be preserved beside our pillows, so that we can slumber with the verses, weaving dreams about Hong Kong bling and Kathmandu drab.

Giri has long been active in the Kathmandu literary scene, publishing poetry in magazines such as La.Lit and anthologies like Of Nepalese Clay and House of Snow. She’s also edited These Fine Lines, an anthology of poems from young female Nepali poets that explored themes of personal desires and struggles. She is also the co-creator of the popular podcast, Boju Bajai, and thus one of the pioneers in Nepali feminist podcasting.

Through these mediums, Giri has been a proponent of speaking the truth, asking difficult questions, and shining a light on topics that are socially stigmatized. Her previous poetry often spoke about injustice in contemporary Nepali society and also the struggle she’s had with her own identity. There are traces of these themes in this book as well:

When I’m asked to pick one, asked where I’m from

I find shelter in the hardened shell on my back,

made from a wet paste of crushed bones,

and like a snail,

I feel, at last, at home.

What Giri perhaps means in this stanza is that she is an amalgamation of her experiences. So the poems that she has written in the past too (“Me too”, “My bastard child”, “When I have a daughter”) find a home within the paperback covers of An Archive.

In a world so fragmented, Giri’s poetry has the power to connect individuals and experiences. As she writes, you could find a home anywhere — in distant lands or in places pretty close — and you can carve words, produce letters, build a dictionary, write your own thesaurus, your own archive of consonants.

archive v. place or store (something) in an archive

This review will be archived along with the book.

***

‘An Archive’ is being published by SAFU, an imprint of Quixote’s Cove, and will be formally launched on Saturday, April 30, at Yellow House, Lalitpur.

Shambhavi Basnet Shambhavi Basnet is an aspiring writer. She has previously written for Nepali Times.

Books

9 min read

Many of the poems in Itisha Giri’s new collection are dedicated to women, talk about women, and diagnose how women occupy the pages but have not been allowed to occupy similar spaces in society.

Features

6 min read

Queer — A celebration of art and activism is not only a documentation of Nepal’s queer community’s celebrations and struggles but also a form of resistance.

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19-related developments that matter

Photo Essays

3 min read

A glimpse into the history of women's education

Perspectives

3 min read

The internalized belief that women should always put the needs of her husband and her family before hers is the product of a patriarchal mindset that begins from the kitchen.

Perspectives

4 min read

Has gender equality actually been achieved or does it only represent a partial shifting of powers from male Khas Arya individuals to women from the same clan?

Interviews

11 min read

In an email interview with The Record, Nepali-Indian poet Rohan Chhetri expands on the ambitions of his poetry, his influences, and his use of the English language.

Film

7 min read

‘Lipstick Under My Burkha’ shows women’s desires without apology.