Features

4 MIN READ

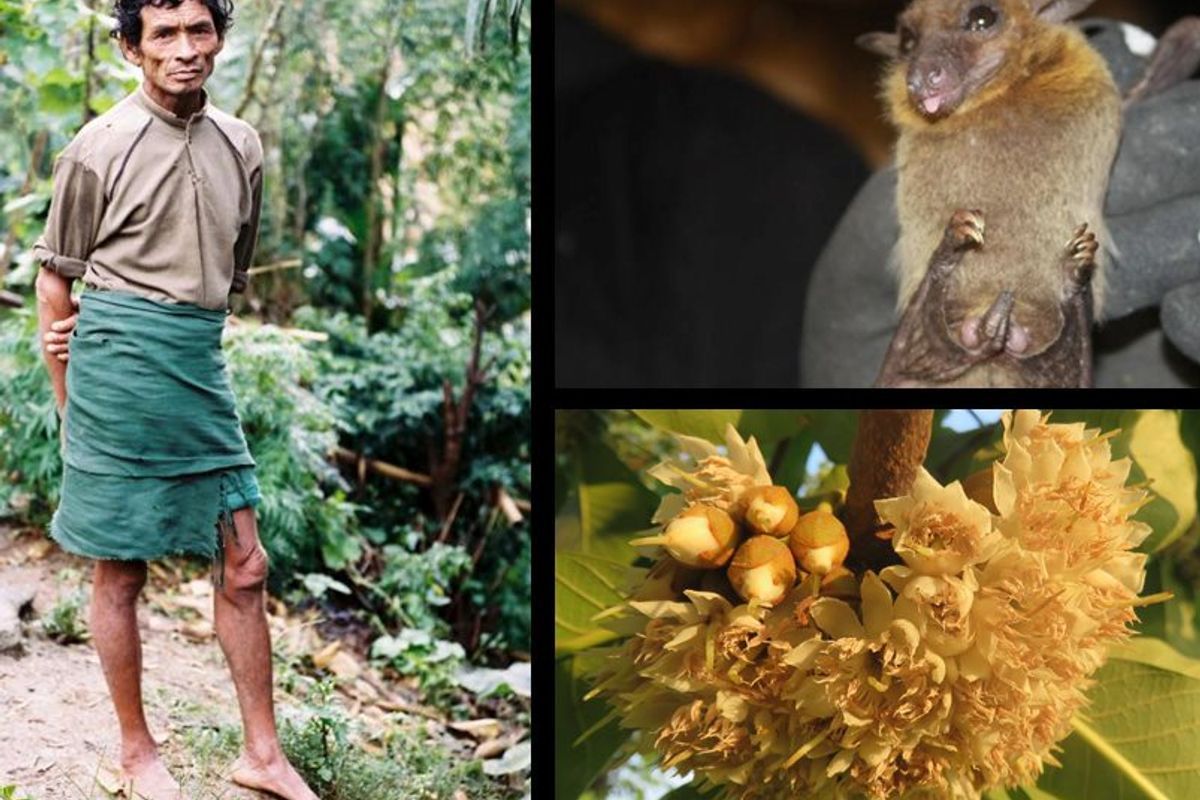

Bats, chiuri trees, and the Chepang community make up a unique ecosystem in the Chure region that is now coming under threat.

Overlooked in the debate over Chure conservation is a highly threatened ecosystem that links indigenous people and nature. The ecosystem connects three major components — Chepang (चेपांग), chiuri (चिउरी), and chamera (चमेरा).

For generations, these three चs have existed in a mutually beneficial system distinctive to the Chure. For one to survive, they must all thrive. When the population of bats flourishes, chiuri (Diploknema butyracea, or Indian butter tree) blooms. And when chiuri blooms, Chepangs prosper.

But in recent years, this harmonious ecosystem is being threatened, and it is not just by sand mining in the Chure hills.

The Chepangs are a marginalized community, residing mainly in Gorkha, Makwanpur, Chitwan, and Dhading districts. Historically semi-nomadic, they only started farming 80 to 120 years ago and rely instead on forest resources. They trade forest products like fiddlehead fern (निघुरो) and chiuri for rice and grains. Chiuri especially is closely associated with Chepangs.

Chiuri is a medium-sized tree native to Nepal that grows in the sub-Himalayan tracts on steep-sloped ravines and cliffs. Oil made from chiuri was once used to light lamps in monasteries and ghee extracted from chiuri seeds is often used for cooking.

“Vegetables that are cooked in chiuri ghee are extremely tasty,” says Ramjimaya Chepang, a resident of Shaktikhor, Chitwan. “But the ghee can also be eaten simply with bread.”

For the Chepang community, the chiuri tree is a source of life and livelihood. Many Chepang communities earn incomes by selling chiuri seeds in different forms, including as sweets, food, medicine, and cosmetics. They eat the fruit and drink its juice. Seeds leftover are used as fertilizer for paddy fields and banana plantations. Chepang women sew chiuri leaves together to make organic plates (टपरी) or feed them to cattle. Healers use chiuri bark juice to treat boils, indigestion, and tonsillitis. Hunters make glue out of chiuri resin to trap insects and use its wood to construct furniture. Chiuri honey is a popular provision today, even outside the Chepang community.

Chepangs even worship chiuri trees and their priests use its seeds for religious activities. Alcohol made from the chiuri fruit is used in festivals and rituals. Cutting down chiuri trees is forbidden in Chepang culture. Only dead trees are used for firewood and to make furniture.

The Chepangs value chiuri so much that they even give trees away as dowry.

“We didn’t have any wealth to give to our daughters but we knew how to use the chiuri for our livelihoods,” says Ramjimaya. “So we’d give chiuri trees away to our daughters so that they wouldn’t be miserable in their new married home.”

This culture, however, is only practiced in some Chepang communities of Makwanpur and Gorkha today.

Shant Bahadur Chepang, a Chitwan resident, says, “We don’t follow the practice now. There aren’t enough Chiuri trees in the wild to collect seeds, let alone any saplings to give to our daughters.”

Chiuri trees in the Chure are indeed disappearing. According to Shiva Prasad Sharma Poudel, central president of the Federation of Nepal Beekeepers, only 20-25 percent of chiuri flowers bloomed this year in Chitwan, as compared to previous years. And one of the primary reasons behind the disappearance of the chiuri is the decline in the number of bats.

Small bats in the Chure region forage for fruits and flower nectar. While doing so, they disperse seeds and pollinate plants. Bats can fly farther than average bees and their larger, furrier bodies allow them to transport more pollen.

Fruit-eating bats are important for chiuri pollination. When bats suck the nectar from chiuri flowers or eat the chiuri fruit, pollen sticks to the fur on their bodies. When they fly to another flower or tree, they transfer the pollen and thus, help in pollination. Locals describe this as the bats ‘playing’ in the flowers.

“We noticed that when bats play in the chiuri flowers, chiuri flourishes better that season,” said Ram Chepang from Siddi in Chitwan.

Sadly, the number of these flying mammals has been decreasing in many parts of the Chure hills, say locals. The primary cause appears to be hunting.

Generations of Chepangs have hunted bats for food. They believe bat meat to be a nutritious and good treatment for diseases such as asthma, gastrointestinal illnesses, joint pain, renal diseases, and tuberculosis. Traditional healers are known to consume its meat for energy.

Chepang men hunt the bats when they come out to forage on the chiuri at night. Hunters place fine strong nets (locally called भुवा) near chiuri trees during its flowering and ripening seasons. Boys use rubber toys or simply their mouths to imitate bat sounds. When the bats approach the call, they are caught in the net and killed immediately.

Hunters even kill pregnant bats.

“During the monsoon, bats visit the chiuri plants while carrying their offspring,” says Dilmaya Chepang, a resident of Shaktikhor in Chitwan. “Killing them eventually kills their offspring, wiping out their whole generation.”

Unlike previous generations, Chepangs now hunt to sell the bats in local markets.

“Bat hunting is no longer for meat consumption in households but also to be sold in local markets in Chitwan,” says Sanjan Thapa, co-founder of the Small Mammals Conservation and Research Foundation (SMCRF).

Before Covid-19 hit Nepal, both Chepangs and non-Chepangs sold bat meat for around Rs 200-250 per bat in the Shaktikhor bazaar. Chepangs say city dwellers often visited this market to buy bat meat. What used to be one community’s livelihood expanded into a commercial practice aimed at outsiders. And now, even non-Chepangs are hunting bats, resulting in an overall decrease in the bat population.

Despite the impending ecological imbalance due to the decline in bats, few people understand the importance of these mammals in chiuri production. To conserve bats, Chepangs themselves must acknowledge the bats’ ecological role in increasing chiuri production, thereby supporting the Chepang community’s livelihoods.

Research is also important in protecting bats. Bats are often misunderstood as bad omens and their conservation isn’t prioritized. Especially after Covid-19, the general perception about bats has become even more negative. Studies about the symbiotic relationship Chepangs share with chiuri and bats will shine a more positive light on these much-misunderstood mammals.

Bats, chiuri, and the Chepang community are components of a unique ecosystem that shows how humans interact with and depend on nature. This unique relationship should be seen as Chure’s asset and must be conserved if we are to teach future generations to cherish our environment.

Aditi Subba Aditi Subba is a conservationist, interested in human-nature dynamics and the global practices of nature conservation by different communities.

Explainers

4 min read

The nation is unprepared for the mass return of migrant workers from destinations across the world

Perspectives

10 min read

Everest has emerged as a marker of the evolution of Nepal-China ties from conflict to collaboration.

Perspectives

Opinions

4 min read

Development and environmental preservation are not antithetical goals

Features

4 min read

Hundreds continue to flock out everyday from the joblessness, hunger and desperation that has come to plague their lives during the lockdown.

Features

4 min read

Bats, chiuri trees, and the Chepang community make up a unique ecosystem in the Chure region that is now coming under threat.

Perspectives

12 min read

Covid-19 has highlighted the potential benefits of small-scale family farming

Features

8 min read

For decades, studies have shown that a warming climate is pushing the treeline to shift upwards across the world — including in the Everest region. But what exactly does this phenomenon mean?

Features

3 min read

Nepal accepts China’s request to jointly announce the new height of the world’s highest peak while risking being dismissed by the international mountain community