Perspectives

6 MIN READ

The constitution mandates the chief justice be a member of a council that makes constitutional appointments while also leading a judicial bench that oversees those same appointments.

Recently, a single bench of the Supreme Court, presided by Justice Hari Prasad Phuyal issued an interim order on a writ filed by Advocate Ganesh Regmi, forbidding the court’s Constitutional Bench from hearing matters related to appointments to constitutional bodies until the question over the composition of Constitutional Bench as envisaged by the constitution is settled.

Earlier, advocates who had filed writs challenging the controversial appointments to the constitutional bodies under an ordinance issued by KP Sharma Oli had asked Chief Justice Cholendra SJB Rana to recuse himself from the Constitutional Bench. According to the advocates, as Chief Justice Rana was present at the Constitutional Council meeting that made those appointments, he had a conflict of interest. Rana eventually decided to recuse himself from the bench. But advocate Regmi’s writ had challenged Rana’s decision, arguing that the chief justice had no authority to unilaterally recuse himself and that Rana needed to be part of the Constitutional Bench, according to constitutional provisions.

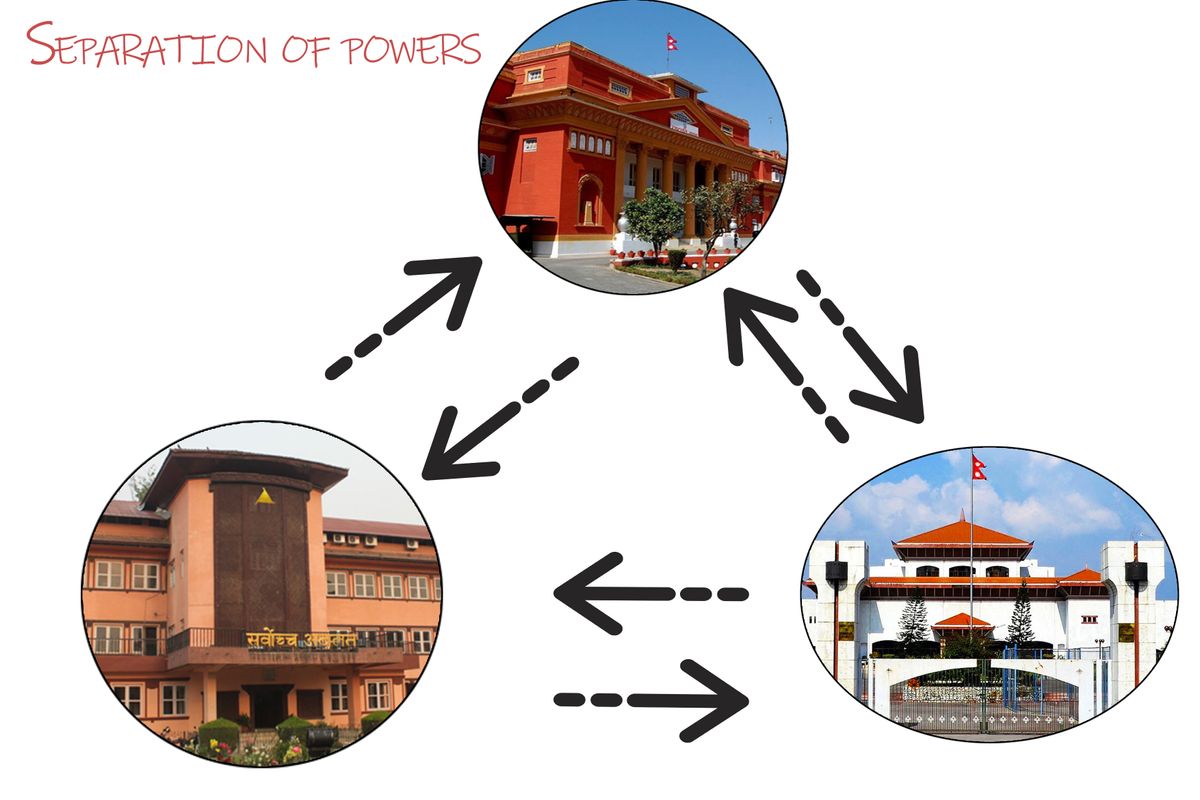

This issue has appeared as a thorny question regarding separation of powers and the role of the judiciary. The Constitutional Council is a six-member body consisting of the prime minister, chief justice, speaker of the House of Representatives, deputy speaker, chair of the National Assembly, and leader of the opposition. The council makes appointments to powerful constitutional bodies like the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority, National Investigation Department, and the National Human Rights Council. According to the Constitutional Council Act, at least five members, including the prime minister, must be present for the council to make any appointments.

However, Oli, when he was prime minister, had issued an ordinance that amended the Constitutional Council Act in order to allow the council to take decisions as long as a majority of members were present. Under this amendment, Oli, in the presence of Chief Justice Rana and National Assembly chair Ganesh Prasad Timilsina, had made 18 appointments to various constitutional bodies. As the House of Representatives does not have a deputy speaker, the presence of three members constituted a majority.

As the chief justice was part of the council that made the recommendations, and the constitution requires his presence on the Constitutional Bench that will hear cases regarding the recommendations, the issue now invokes much wider implications regarding separation of powers in the new Nepali constitutional framework.

United States founding father James Madison, in the Federalist Paper 47, argued that the accumulation of all power in the same hand leads to tyranny. Earlier, the French political philosopher Montesquieu, in his book The Spirit of the Laws, stressed the need to divide power between three organs of the state -- the legislative, executive, and judiciary -- in order to have proper checks and balances. It is this idea that forms the basis for the separation of powers in most democracies, including Nepal. The legislature makes the laws, the executive implements them, the judiciary adjudicates any conflict between the two.

However, in recent times, these dynamics have changed. Constitutional supremacy, influenced by the American legal tradition, has now emerged as a major norm in the democratic system, as opposed to the parliamentary supremacy of British common law heritage.

The power of judicial review, which ensures that the action of the executive and the laws passed by the legislature don’t conflict with the constitution, ensures constitutional supremacy. And it is precisely because of this function and power that the institution of the judiciary is increasingly being seen as an alternative power center as it has the power to annul laws made by the people’s representatives in the legislative. Consequently, across the globe, judicial pronouncements are being scrutinized through a partisan lens and the judicial selection process itself is blatantly politicized. In this regard, Nepal’s judiciary is no different.

Article 128 of the Nepali constitution grants the Supreme Court, the apex court in the country, the final authority to interpret the constitution and the law of the land. Thus, appointments to constitutional bodies, the reservation policy, formation and annulment of political parties, and the dissolution of Parliament are all issues under judicial review.

Such judicial exercises of power have forced politicians to abide by legal and constitutional norms, not just political actions. But it is the power entrusted to the judiciary by Article 284 of the constitution that shatters the traditional separation of power, turning the Nepali judiciary into an even more powerful institution.

Article 284 of the constitution envisages the Constitutional Council, its composition, and its powers. A council that largely comprises political members, the chief justice too has influence. By creating a judicial stake in a constitutional yet political council, the constitution of Nepal has itself tested the fragile check-and-balance mechanism within the parliamentary system.

Making matters worse, Article 137 of the constitution mandates that questions involving serious constitutional interpretations are to be settled by the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, headed by the chief justice. Consequently, the chief justice, constitutionally entrusted to recommend names to constitutional bodies, is also mandated to preside over the bench that will hear any challenges to the appointments to which he was a party. Therefore, the recent decision by Justice Phuyal to settle this contradiction between the executive and judicial role of the chief justice before any further decisions are made was necessary.

The issue raised here is not just a matter of temporary interest, but one that has wider implications for the functioning of democracy in Nepal for years to come. Therefore, it is imperative that the court address the issue by taking a holistic rather than restrictive approach to assessing the overall scheme of the constitution and the Nepali framework of separation of powers.

Phuyal’s order has created ripples in the Nepali the legal field. Advocate Om Prakash Aryal, who had earlier filed a writ against the appointments to constitutional bodies, has once again petitioned the court, asking for an early hearing on the appointments. A former Supreme Court justice has also involved himself in the matter.

That the chief justice is part of a council appointing members to constitutional bodies while also leading a bench that evaluates those very appointments appears to be a clear contradiction of the separation of powers. Whatever the Supreme Court decides, the peculiar position of the chief justice within the constitutional architecture must be settled, sooner if not later.

Robin Sharma Robin Sharma is a graduate of NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad and holds an LLM from Tel Aviv University, Israel. He is a Kathmandu-based lawyer.

Features

13 min read

For the victims of war-era atrocities to whom Nepal has continually shown an unwillingness to deliver justice, a bleak future awaits

Perspectives

Longreads

47 min read

Sam Cowan returns with fresh insights on the drafting of the Nepal's 1959 constitution, the subsequent general election, and a new witness to King Mahendra's coup d'état.

Photo Essays

4 min read

When the pandemic forced countries to go into lockdown, closing international borders, Nepali migrant workers in Saudi Arabia were forced into dire living conditions. This was their plea.

Week in Politics

4 min read

Week in politics: what happened, what does it mean, why does it matter?

Recommended

Perspectives

7 min read

Rupa Sunar’s act of resistance not only sparked the predictable rage of Bahuns and Chhetris but also unmasked many Janajatis who see themselves as crusaders of justice for the marginalized.

Perspectives

6 min read

Federalism appears to be working in exactly the two places—with distinct regional identities—where it was most likely to work.

Explainers

9 min read

Nepal’s caste system continues to crush and kill Dalits

Perspectives

6 min read

Non-Resident Nepalis embody the diversity and pluralism of Nepal and its polity.