Perspectives

8 MIN READ

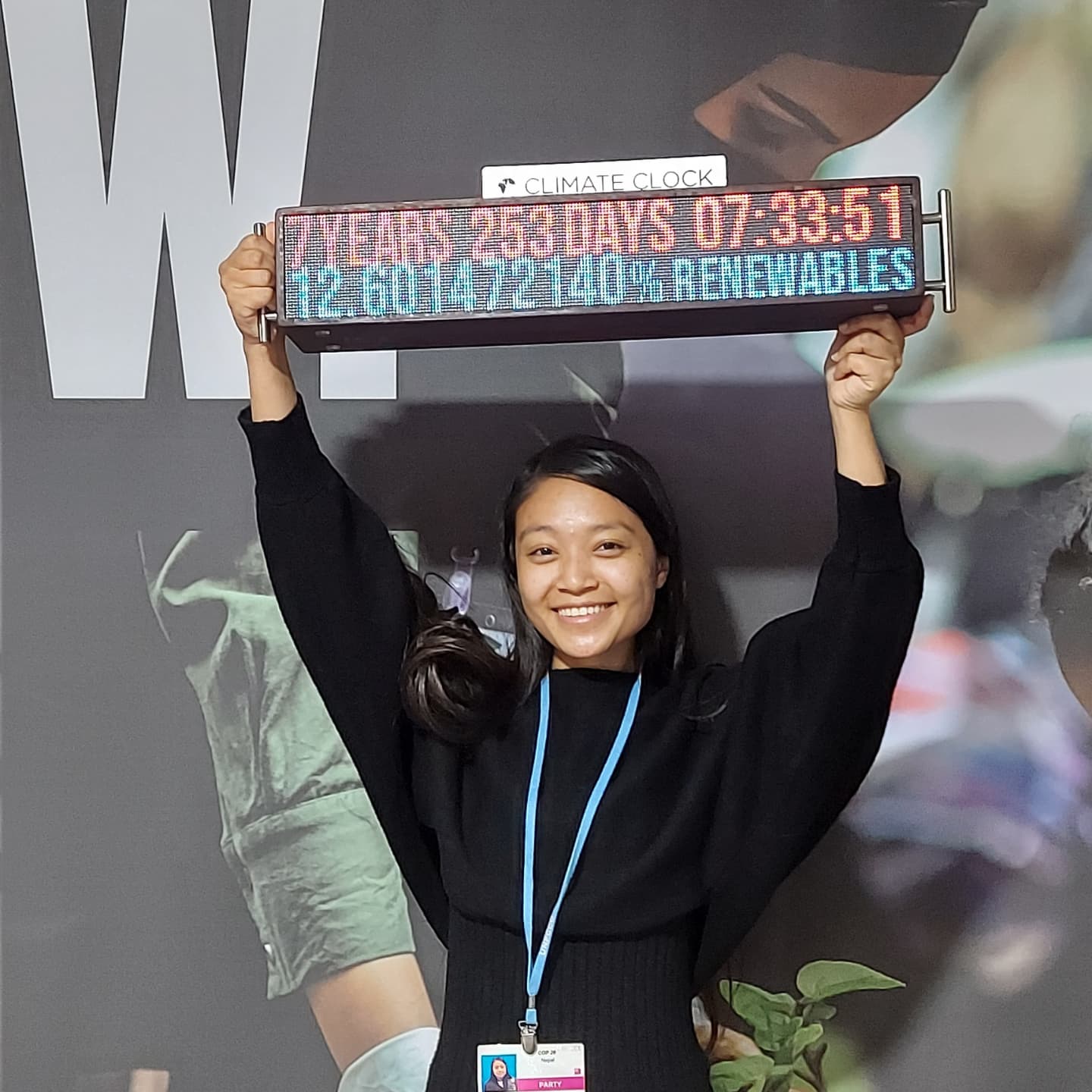

One young Nepali climate justice activist reflects on her experience attending COP26 and illustrates how the conference ultimately let us all down.

I wasn’t even born when the first United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as the Conference of Parties (COP), was held for the first time in Germany in 1995. But at 23 years of age, I got an opportunity to attend the most recent of these meets — COP26.

This year’s summit was hosted by the United Kingdom in the Scottish Event Centre (SEC) in Glasgow between October 31 and November 13, under the theme ‘Together for our planet’. Alok Sharma, a UK member of parliament, served as president for the conference, which was touted as the ‘last best chance for humanity’.

COP26, originally scheduled for 2020, was delayed by a year due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Decades of progress in the fight against poverty and the climate crisis were reversed by the pandemic and the disruptions it created across the world. A recent World Bank study estimated that an additional 88 to 115 million people were likely to be pushed into extreme poverty this year. The pandemic illustrated how quickly and drastically the socio-economic status of vulnerable countries can change for the worse.

Concurrently, climate and weather-related disasters have surged five-fold over the last 50 years. Action on the threat of climate change thus demands urgency to deliver progress on the ground and protect vulnerable countries and their peoples, who’ve already been impacted disproportionately by the pandemic, by putting them at the center of every plan and decision.

It was with this concern in mind that I keenly followed announcements and updates related to COP26 with curiosity, especially in light of COP25’s disappointing outcomes and inclusivity concerns. After passing through a string of tests and clearances, I was even able to attend the conference in the UK. I was cautiously optimistic, as COP26 was billed as the most inclusive COP ever. My doubts were alleviated when COP26 president Sharma personally assured me and my fellow Nepali youth activists that voices from the Global South would not be left unheard and unrecognized.

However, attending the conference and watching the discussions taking place in front of my eyes, I felt frustrated and betrayed. Youth voices were included in several high-level statements and photo-ops but were largely missing in decision-making spaces. Only a small number of countries, including Nepal, brought young people with their national delegations. The participation of young people from the Global South in the negotiations was also constrained by Covid-19 restrictions. A few cherry-picked young voices were invited to speak in several segments, but I personally didn’t feel the positioning was genuine. Instead, it felt more like an effort to tick the box of youth quota. My sentiments were echoed by youth activists and civil society leaders around the world.

Still, I don’t believe that the conference was a total failure. Its main agenda included discussions and agreements on finance, adaptation, mitigation, and partnership. Campaigns like Race to Resilience and Race to Zero were quite popular and are expected to deliver on their desired outcomes. The conference thus did achieve a few breakthroughs:

For one, the Glasgow Climate Pact “requests” countries to “revisit and strengthen” their climate pledges by the end of 2022, calling for a “phasedown” of coal. It also “urges” developed country parties to at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation and sets up processes towards finance for loss and damage. The Glasgow text also welcomed the findings of the IPCC’s ‘Code Red’ report under “science and urgency”.

Second, the Article 6 Rulebook was finalized after six years of negotiations, closing off the longstanding issue of “double counting” emissions. There was also a provision allowing the use of pre-2021 credits generated under the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism.

And third, a declaration on forests and land use, was signed by more than 130 countries, promising to “work collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. A global methane pledge was also signed by 105 countries to cut their methane emissions by 30 percent between 2020 and 2030.

However, little tangible progress was made on the critical issue of loss and damage, as the topic was shelved until next year for now, but who knows until which year and which COP?

The most important agenda was to keep the world on track of a 1.5-degree survival threshold, and this is where the conference largely failed. Even if all the countries meet every target of their climate action plans, i.e., Nationally Determined Contributions, global temperatures may still increase by up to 2.4 degrees Celsius by 2100. Even if countries meet their long-term net-zero promises, temperatures may only be limited to around 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2100. Furthermore, wealthy nations with the highest historical and present-day emissions failed to raise the $100 billion annual climate funding they had promised to vulnerable countries like Nepal. Based on current speculation, this aim will not see fruition until 2023.

The most interesting yet painful observation for me was seeing that fossil fuel lobbyists outnumbered national delegations. Over 503 of these lobbyists continued to block the progress of the summit and were organized to represent the interests of oil and gas companies. Glasgow made clear to me that despite decades of lip-service, the world is still trying hard to continue with business as usual. And that is not something we can afford to do today.

There have been debates globally over whether COP26 was a success or failure. For Nepal, the climate crisis does not begin at 1.5 degrees; it is already worse at the 1.2 global average. Climate change is not something that we are anticipating in the near future — we are already suffering from its consequences now, and those repercussions are only going to become more severe in the days to come. Even if we are able to achieve the 1.5-degree target, which seems impossible to reach as of now, one-third of our Himalayan glaciers will melt by the end of this century. Adaptation to climate change is central to all of Nepal’s plans and policies for climate change but no amount of current adaptation and mitigation efforts can negate Nepal’s climate vulnerabilities.

What stayed with me the most at the end of the conference, however, is how I felt. Every day, as I walked through the conference venue, I felt ignored and unwelcomed. There were times when I spent hours on a chair in the Action Hub doing absolutely nothing. While attending the core negotiation meetings, I saw how world leaders were bargaining over our lives by discussing whether to ban fossil fuels or not, when all of us clearly know the risks. For instance, it was shocking to see countries like the United States opposing the proposal of finance for loss and damage, especially as the US has been making headlines stating that climate science is back in the White House with the new administration of Joe Biden. Their opposition clearly shows how deeply they care about climate justice.

The progress inside the negotiations moved at the speed of a sloth while the intensity of climate-induced disasters continues to grow at a frenetic pace. I participated in lobbying meetings with delegations from many countries, but in the end, they all concluded with hollow promises and thinly veiled superficial appreciation for the young activists. As if to hammer in the discrepancy between the Global South and the Global North, there was a stark difference in the food served at the COP venue to representatives from either side. This last issue only served to make my experience all the more unpleasant.

On a more positive note, I was very inspired by negotiators from Least Developed Countries, African groups, and Small Island Developing Countries. They were not willing to compromise and pushed the Global North hardest for reparations to the Global South.

There were demonstrations inside the COP venue, usually in front of the plenary. But the strict security only served to terrify us. I must admit, the atmosphere outside the blue zone was completely different — very vibrant and inclusive. Thousands of youths and people from different sectors protested, chanted, and rallied, demanding climate justice. People from the Most Affected People and Area (MAPA) region, indigenous peoples, and people living with disabilities were at the forefront of the march. Even as older leaders from across the world let us down, time and again, we showed that we would not stay silent and tolerate the consequences of inaction over these past 27 years.

As the leaders of wealthy nations congratulated each other for a successful COP, I left the COP venue in great dismay. The outcomes were nowhere near adequate to deal with the scale of the climate emergency at hand.

Shreya Kc Shreya KC holds a Bachelor's degree in Environmental Science and has served as national network coordinator for Nepalese Youth for Climate Action (NYCA), where she is currently an advisor. She is Youth Climate Change Champion for UNICEF South Asia and received the ‘Hidden Eco-Hero Award’ in 2020. She was a delegate to COP25 and also a part of the Nepali national delegation to COP26.

Perspectives

Film

8 min read

This feature documentary highlights the direct and indirect costs of climate change through three unique stories across Nepal, linked by its central theme: water.

Features

4 min read

Tiny mountain birds are like the superheroes of the bird-world, surviving by adapting to freezing temperatures with the help of their feathers.

Perspectives

10 min read

Everest has emerged as a marker of the evolution of Nepal-China ties from conflict to collaboration.

Explainers

21 min read

We have not dealt with a disease like COVID-19 in over 100 years.

Features

6 min read

Glaciers are retreating across the Himalaya and this is bound to have significant consequences for the ecology of the region and the livelihoods of its people.

Features

6 min read

Two months ago, unprecedented floods brought about much destruction to Melamchi but residents have largely been left to fend for themselves.

Features

6 min read

When it comes to climate change, Global media attention has stayed on island nations but the Himalaya have their own unique vulnerabilities.

Features

4 min read

A research team is being set up to investigate rhino deaths at Chitwan National Park