Features

11 MIN READ

Covid-19 managed to break all geographical boundaries to reach the remote village of Lalu – and the couple who operate its only private school.

Like most other villages in the district of Kalikot in Karnali province, Lalu, a village of about 6,000 people, remains disconnected from the outside world. The nearest gravel road is in Kalekhola, about three to four hours away, where narrow trails meander over rugged hills and green passes. Reaching Kalekhola is a feat in itself, as the bus from Nepalgunj, which lies in the country’s plains, can take 10-12 hours, provided there are no landslides on the way.

On the way to Lalu, porters carrying heavy loads on their backs stride carefully along the slender paths. Even the sick are carried on dokos or thick blankets wrapped around branches to the health post in Lalu.

Along with Rupsa, a village about three hours away, and Kumalgaun, Kotbada, and Malkot, Lalu makes up Naraharinath Rural Municipality. The municipality’s remoteness and the lack of material prospects dissuade outsiders from visiting. So, when two dozen Covid-19 cases surfaced one fine October morning in Rupsa, the news sent shockwaves through the entire rural municipality. Caught in the scramble were a newly married couple, founders of the Modern Model Residential School in Lalu.

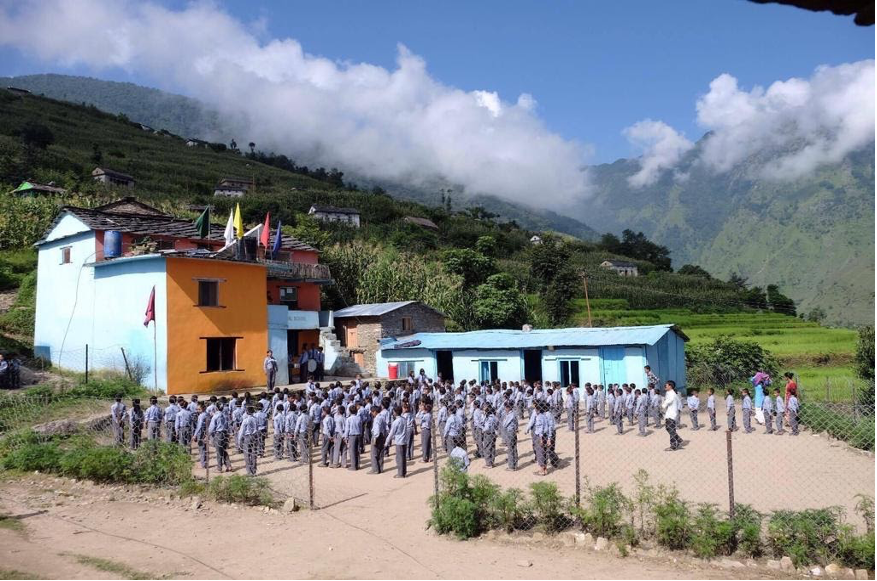

Prakash Bista and Shomi Basyal run the only private, not-for-profit school in Lalu. The Modern Model Residential School is a primary school with 248 students, 32 of whom stay in the school’s hostel. Bista, a native of the village, founded the school in 2010 in the memory of his parents, whom he lost within an interval of nine months when he was in his late teens. Basyal, a resident of Kathmandu, met Bista when they were pursuing a college preparatory course in Kathmandu. Their values synced and they fell in love. In 2016, after completing her Bachelor’s degree, Basyal moved to Lalu to help Bista run the school. In February 2020, just a month or so before the Covid-19 pandemic hit Nepal, they got married with a traditional wedding ceremony.

I met the couple in early March at a roof-top restaurant in New Road. Bista was in Kathmandu for a nasal surgery that he needed to overcome his breathing difficulties. After two months of an agonizing wait, he had finally secured an appointment at a government hospital.

I was interested to hear about the couple’s experience during the lockdown. Bista and I share the same alma-mater, Soka University. When I had last checked-in with him in October, he had told me that even remote Rupsa was dealing with cases of Covid-19. I was perplexed at how the coronavirus had overcome all geographical divides to travel to secluded areas like Naraharinath Rural Municipality and how the couple and their school had dealt with the pandemic.

“We knew that the virus would reach our remote villages one day but not as suddenly as it happened,” Bista said.

Teaching during the pandemic

On May 31, 2020, two months after the nationwide lockdown was enforced, the federal Ministry of Education issued a 13-page directive to facilitate teaching during the pandemic. The document acknowledged glaring resource inequities between various Nepali schools and attempted to provide specific instructions. Those schools whose students could afford laptops and an internet connection were instructed to operate virtually. Schools that could reach their students via radio or television were required to make arrangements accordingly. One such category was for remotely-located schools, like Modern Model Residential School in Lalu, that do not have any means to reach out to their students. The government allowed these schools to operate in-person in a community setting, provided that they followed safety protocols.

“Our school fell in the remote category,” Bista told me. “Most students come from impoverished families. Some of their parents depend on the school for their incomes. All of the hostel students are either orphans or have single parents.”

By this time, Naraharinath Rural Municipality, complying with the government-mandated lockdown, had suspended all travel in and out of the villages. But the lockdown was beginning to tire people mentally and calls to reopen schools grew.

“In early May, we applied for a $2,000 grant through Impact Schools, our school’s charity partner, to purchase masks, temperature guns, sanitizers, disinfectants, and water filtration systems to keep children safe should schools open,” said Bista. “Then, in June, we organized a socially-distanced school-parent meeting, where we informed the parents of different measures the school administration was taking to keep children safe.”

Fear of the coronavirus wasn’t the only thing troubling the rural municipality. In June 2020, heavy rains and floods killed 16 people and displaced over 200 families.

“There was a lot of chaos around us. With financial support from the Britain-Nepal Society (BNS) and in coordination with the municipality office, we distributed a month’s worth of food to 160 families affected by Covid-19 and the monsoon rains,” said Bista. “We were in the recurring state of emergencies.”

On June 23, 2020, Bista and Basyal decided to reopen the school but insisted on maintaining strict safety measures.

“After each shift, workers disinfected the benches and desks,” said Bista. “Other schools waited to see if our school developed any cases before deciding to reopen.”

Meanwhile, thousands of migrant laborers were making their way back to their homes from the cities. And inevitably, in July, at a government quarantine center at the entry point to Naraharinath Rural Municipality, a 10-month-old infant tested positive for Covid-19, the first case in the municipality. The infant and his mother were quickly placed in isolation and the disease did not spread.

With just one Covid-19 case so far, Naraharinath Rural Municipality decided to reopen all public schools.

“The CDO [Chief District Officer] had lambasted one school principal over a phone call on why the latter had reopened the school without any safety measures,” said Bista. “Despite the push back from the CDO, various school principals continued to operate in-person classes without safety measures.”

On September 17, the last 20 people infected with the coronavirus in all of Kalikot district recovered and The Rising Nepal, the state-owned English daily, declared that “Kalikot becomes a coronavirus free district.”

The mood was jubilant, but it wouldn’t remain so for long.

By October 2020, Bista and Basyal had been running Modern Model Residential School and its sister school, the Kotbada Impact School in Kumalgaun, for nearly four months into the pandemic. They were following all World Health Organization (WHO) and Nepal government-mandated safety guidelines, such as requiring students to wear masks and wash their hands properly, they said. To ensure social distancing, the school conducted classes in two shifts. Students sat in separate benches or at polar ends during class.

In mid-October, a teacher who had just visited the nearby district of Surkhet came back to teach in Rupsa village. He was not feeling well. A few days later, others began to fall sick in Rupsa.

The news had not yet reached Bista and Basyal, who were planning to travel to Pokhara for the Dashain break. Bista had been in Rupsa the same week as the teacher, handing out protective gear. On October 19, the couple left Kalikot and reached Nepalgunj the same day.

“When we arrived in Nepalgunj, we realized that we had access to a testing facility and we wanted to see if we had caught the virus. If we had tested later, we would not have been able to ascertain if we caught the virus in the city or from the village,” said Bista. “It was a test to know if the virus had reached our village. We were confident that we did not have it.”

The couple left on a 50-minute flight to Kathmandu for October 20 before the results could come in. There are no direct flights from Nepalgunj to Pokhara. Since they had taken the test, they maintained social distance and sat in separate corners with face shields and masks.

On the evening of October 21, at a Kathmandu hotel, Basyal received a text from the testing center stating that she had tested negative for Covid-19. A couple of hours later, Bista received a call -- he had tested positive. The doctor on the call asked him to immediately self-isolate.

“Everything changed after that,” Basyal recounted. “We slept on two different beds and distanced ourselves.”

Contracting Covid-19

The previous day, on October 20, an elected official from Rupsa village had informed a school management committee (SMC) member of the Modern Model school that the village had reported over two dozen cases. The official too had symptoms and was self-isolating. He was worried that people were going to die.

“Do you have any masks or sanitizers? People are falling sick everywhere in the village,” the Rupsa official said to the SMC member, according to Bista. “Are we going to die? Everyone is panicking.”

Bista had surplus masks and sanitizers at his school but the government had sealed the village and no one dared enter Rupsa. The next day, as he remained in isolation, the Naraharinath Rural Municipality chairperson called to ask if he could volunteer to go to Rupsa with masks and sanitizers.

“The chairman thought that we would be happy to do so,” he said. “I told him that I too had contracted Covid-19. He could not believe it as I always wore masks and used sanitizers.”

Bista informed his friends and colleagues that he’d tested positive and asked those who had come in contact with him to isolate themselves and take the test, if possible.

“School workers, staff, and hostel children understandably panicked,” he said. “The hostel area was sealed and a medical team conducted Covid-19 tests on all the hostel children, staff, and schoolteachers. Fortunately, they all tested negative.”

After spending the night at his Kathmandu hotel, Bista informed the management about his infection and the couple was duly evicted. Bista’s health had started to deteriorate and Basyal attempted to find other hotels. However, no one was willing to admit a Covid-19 patient. They eventually managed to get a doctor friend to help them find a place to stay.

Two days later, at around 11 pm on October 23, Bista’s oxygen level dropped and he was rushed to the Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital in Teku. He had a 103 degree fever. For seven days, Bista languished at the hospital, suffering from the effects of Covid-19.

Bista was lucky, as at that time, the government was still covering Covid-19 patients’ medical costs. The day Bista was discharged, on October 30, 2020, the government changed its policy.

“I was lucky. I could not have afforded my care in a private hospital,” Bista said.

The government’s reversal was challenged at the Supreme Court and the government was forced to compromise, pledging to provide free-of-cost treatment to Covid-19 patients at all state-owned hospitals.

“The Covid-19 pandemic changed us. It expanded our perspectives,” the couple echoed just a few minutes apart.

Bista understands the value of education. He went to a small liberal arts college in California, called Soka University, as one of its first two Nepalis. In his freshman year at Soka University, the Orange County Registrar named Bista among the 100 people who had influenced Orange County, one of the richest counties in the US. After graduating in 2017, he received a full-ride scholarship to pursue a Master’s in Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the London School of Economics. He returned to Nepal in 2018.

Basyal completed her Bachelor of Social Work degree in 2016 and joined the school in Lalu the same year.

So by 2020, the couple were familiar with the difficulties of running a school in a remote village. When the pandemic hit, they took it slow and relied on expert advice.

“We did not buy in panic. We followed what scientists and doctors were saying. That led us to have no cases at our school,” said Bista.

Covid-19 has exacerbated the difference in educational outcomes in urban and rural areas, and along class lines. Experts say that pandemic will continue to affect future outcomes.

“People casually remark that a year’s loss in education is nothing. They think students can recover what they missed the previous year. But it’s not like that. A year's loss generates cracks in the foundation that students have painstakingly built over the years.” said Bista.

But Basyal believes that there are lessons to be learned from the pandemic.

“Covid-19 had good aspects too. It made us more proactive than before and it led us to realize how education helps to make informed decisions. Because children wore masks the entire year, we did not have to suffer from other seasonal cases of flu and communicable diseases, which would hit us every year.

Bista recovered from Covid-19 but the experience has left him with consistent respiratory problems, which was the reason why he was in Kathmandu when we spoke. Despite their ordeal, the Model Modern Residential School managed to end its academic session last week without mishap and is now on a month-long end-of-year break.

“We are going to take positives from the pandemic,” said Basyal. “And we will build on them.”

COVID19

Features

2 min read

Tourism entrepreneurs, workers cautiously welcome the country’s opening up again

Features

6 min read

A year ago Nepal first went into lockdown to prevent the spread of Covid-19. A year later, new cases are rising once again.

Explainers

9 min read

Elected representatives and officials across the bureaucratic spectrum have used the Covid-19 crisis as yet another opportunity to amass wealth

COVID19

News

4 min read

The valley records another highest daily rise in cases, but efforts at contact tracing haven’t yet begun

Opinions

7 min read

The insidious myths around virginity continue to disempower women

COVID19

Features

4 min read

Nepal’s first three Covid19 deaths could have been avoided with timely ambulance services and adequate medical care

COVID19

Perspectives

5 min read

The world’s largest missionary movement cannot be blamed exclusively for its role in the Covid19 pandemic

Features

4 min read

Hospitals that don’t abide by the MoHP’s directive won’t be able to continue operating