Writing journeys

12 MIN READ

Social science researcher Sabin Ninglekhu provides prudent useful advice when it comes to academic writing, especially the longer kind, in this week’s Writing Journey.

“Writing a dissertation can be a lonely process,” writes Sabin Ninglekhu in this week’s Writing Journey. It’s a journey, he says, “filled with self-doubts.”

I know this reality up close and personal. I gave the better part of a decade of my life to my M.A./Phd journey. Some of it was fun, much was rewarding, but all of it a tough slog. Sabin ji writes of the ghosts that blocked his path. Nasty blue demons blocked mine.

Sabin ji’s reflections here are honest and helpful. Writing a dissertation is a long hard road. But he made it, and, as they say, “what doesn’t kill you…”

Sabin ji shares some excellent advice here – advice that applies to any long project, I think. I can summarize his tips in 18 short words: Let go of the fear, collaborate, get on the bus, take ownership, look within, and ignite the fire.

It’s all great advice, but I’d like to amplify one point in particular: It’s hard to show your work to someone else but, oh, so crucial to do so. I’ve learned that if something’s important, I don’t submit it without showing it to at least one other person first. I might have a lot of experience writing, but what that experience tells me, most of all, is how little I know – and that I’d be a complete idiot not to get feedback and an outside view on anything that’s important.

Also, as Sabin stresses, showing a draft to someone else makes the process much more social, much more collaborative.

Sabin’s a good storyteller. He deploys a trick that several of our authors have also used: he ends the essay with a quick reminder of how he started it.

And here’s how I’ll end: Dissertation writing may be a lonely process, Sabin ji, but, by sharing, you have made us part of your journey, and we have made you part of ours. We are all better off because of it. Working together, we can defeat those ghosts, we can slay those demons.

Sabin holds a PhD in Human Geography from the University of Toronto, Canada, focusing on informal politics and urban poverty. In March 2021, he completed a four-year-long postdoctoral project on post-disaster urban rebuilding funded by the Earth Observatory of Singapore at Nanyang Technological University. Since October 2021, Sabin has been co-leading a long-term research project titled ‘Heritage as placemaking: The politics of erasure and solidarity in South Asia’. Sabin also writes essays and op-eds for The Record, The Kathmandu Post, Naya Patrika, and Chetlung, and occasionally translates popular pieces from Nepali to English. In his head, Sabin is also a ‘ball boy’ for the Arsenal Football Club.

***

The ghosts that block the road: Personal tips for dissertation writing

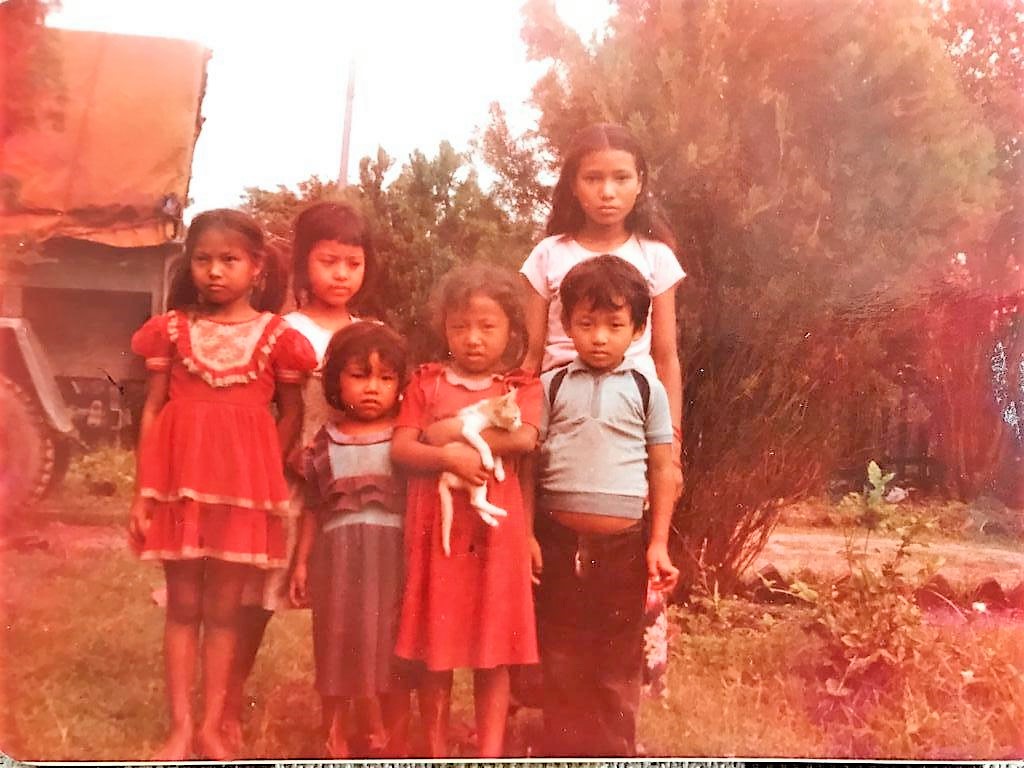

I was born in Dharan. I spent my childhood in this eastern foothill town, which has a reputation as a place filled with storytellers, or guffadis, those with keen ears for stories. There is something in the eastern air that makes good stories. I like to think that I am a good listener of stories. I like telling them too.

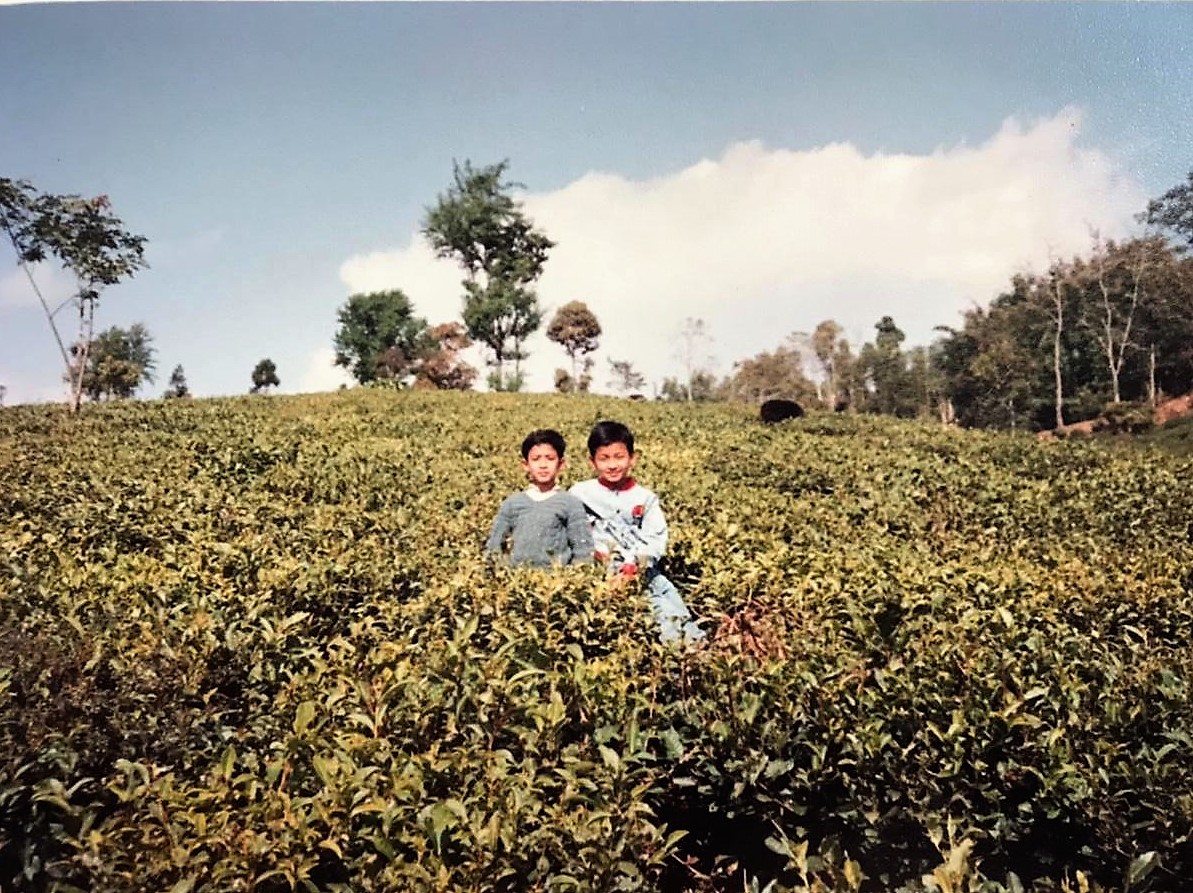

After Dharan, my family moved to Ilam. We went where the government sent my parents. In Ilam, after a two-hour walk north of the bazaar, one arrives at Futuk, my maternal village. People in Futuk no longer walk: roads now go everywhere, cutting across paddies, rivulets, and forests. I have many happy memories of Futuk. My mama, my maternal uncle, collected comic books. A series on the phantom superhero Betaal dominated his tall pile. My favorite 'time pass’ while in Futuk was to lounge about after the morning meal on the patio overlooking the spread-out paddies below, and spend hours on end going over pages after pages of Betaal. Those were the first ‘story books’ filled with fantasy that I read.

In Ilam, another kind of story colonized my impressionable young mind – that of ghosts. During Dashain, we would play football on the school daanda perched atop a hillock. The ‘ball’ was the gallbladder of a pig, filled with air pumped through a pipsing, a thin bamboo pipe made for drinking tongba, a millet drink. It was ours to claim thanks to the sacrificial pig that fell that morning.

After arriving home in the evening, we would find an uncle or two, tipsy with raksi, tying a piece of petrol-drenched cloth to the end of a short stick. We’d ask what he was up to. “It is getting dark,” he would say, casually. “They show up out of nowhere and block my path. They refuse to make way. They don’t budge. The fire helps.” With the flick of a lighter, the uncle would ignite the fire and walk away, leaving us with scary images of ‘they’, the ghosts that block the road.

The stories that filled the eastern air provided the spark that continues to fire my curiosities. When out and about, I am always on the lookout for a story or two. To me, looking for stories does not always mean visiting faraway places and witnessing big events. I feel like every ordinary human being is a walking encyclopedia carrying extraordinary stories that they probably would not mind sharing with a sincere listener. And every story, as personal as it appears, has global resonance.

I do not consider myself a ‘writer’ because to me, writing is a professional field that demands a particular passion and skill set that I do not have. I am primarily a social science researcher. As a researcher, I write. I write book chapters and journal articles. I like writing, even if it’s hard sometimes. There are writings that are fun too. I am currently working on a book project that is part fun, part frustration, but mostly fulfilling. I also like to write essays and op-eds, both in English and Nepali.

I completed my Ph.D. in 2016. It feels like a major accomplishment. Today, a few years afterward, it feels satisfying to reflect on the experience. But at the beginning of the journey, it was anything but satisfying. It was so hard to write. I share this reflection with the hope it will help graduate students working on dissertation projects.

Writing a dissertation can be a lonely process. To me, for the most part, it was also a process filled with self-doubts and an inferiority complex, some of which was perhaps rooted in the ‘imposter syndrome’. For the longest time, I had reservations about sharing my draft paragraphs and chapters. I felt my phrases and sentences were inefficient with no sense of purpose or direction, and I worried that the thoughts and arguments they carried would expose me. I would be ‘found out’. I was afraid of being judged.

I was lucky to find an excellent advisor in Katharine Rankin. She was not only passionate about my work, but also persevered in bringing it together. But even her faith failed to instill enough confidence in me to fearlessly share my drafts with her. So, if I were to pick one piece of advice from my experience, it would be this: Let go of the fear and share your incomplete work. That is the first step toward making writing a less lonely process. The idea behind sharing is to make it a collaborative process, of course, led by the author, toward a more complete work.

One of the most useful and practical pieces of writing advice that I have received so far is this: the only way to write better is by writing regularly, even if the words do not seem ‘perfect’. This was from Katherine. View writing as a ‘9-to-5 job’. There is nothing sacred about writing. Sometimes, to get the job done, writing has to be treated as exactly that, a job. It is like going to an office that you do not always like. It does not matter if you are not up for it or not. You have to write. It is your job. To this day, I follow this advice, like a mantra. If writing leads to boredom and monotony, embrace it. There is no other choice.

Here is my third piece of advice: If squinting at the computer screen does not help, get on the bus with a pen and paper. Removing the screen from in front of your eyes can set your mind free. Sometimes, ‘profound’ thoughts mistime their arrival. They appear when you are in the shower. They pop up when you wake suddenly in the middle of the night. They appear while you are sitting on the toilet. Write them down on your phone before they flush away. Talk to the mirror with the audio recorder on. Email your thoughts to yourself. Find a friend, buy her a cup of coffee, and make her listen. If it helps, it is also okay to go to a bar with a laptop.

Sometimes, inspirations are found in the mundane every day. For example, I once picked up a birthday card for my niece. I was in a rush. As soon as I paid, I found a spot by the counter and scribbled something on the card. It came out like this, “Too bad you continue to be young because by the time I am at your place to hand this card over to you, you will be in bed while we will be downstairs partying. Happy birthday!” I lifted my head up and looked down again at the words, only to be miffed at my lack of creativity. The shop attendant said something that carries value to this day, “Keep in mind that no one else has written what you just wrote. No one will likely ever write what you just did. These words will always be yours and yours alone.” I was not proud of what I had written but what the woman said struck a chord – to take ownership of my words and my thoughts, as if they mattered. And they do. That is my fourth piece of advice for writing.

This message of owning your words was drilled home more powerfully in my case when I stumbled upon AbdouMaliq Simone’s writings. Simone is an influential African-American scholar who writes mostly about Asian and African cities. While researching the ‘slum’ as my Ph.D. focus, I was my own worst critic in an unhealthy way. I would spend days on end judging my own insights and ideas, my ‘findings’, with disdain. This was until I came across Simone, who espouses a different viewpoint about the city in the global South. He believes that it is not just through the ‘master plan’ that cities and urban lives are made and remade; they are (re)made just as much in the spaces of the every day – spaces filled with experiments, encounters, and accidental outcomes, some planned but not always anticipated.

This way of ‘seeing’ the city resonated with me because this was the type of conversation I used to have with myself about my ‘findings’ vis-à-vis Kathmandu and its ‘slum’. Upon reading Simone’s work, even as a young graduate student, it felt as if I was having a conversation with the seasoned Simone on equal footing. As such, his writings enabled me to look for validation not elsewhere but within. From thereon, I could more easily take ownership of my thoughts. Owning the words became less difficult. My fifth piece of advice: The source of validation is to be found in the struggle within.

Every writer reaches a low point. I reached my low point with the Ph.D. in 2010/2011. It had drained all the energy from me. I even had to see a counselor. But new energy came from an unexpected source: an unrelated political campaign. It recharged my emotional and intellectual batteries.

‘Stop Monsanto in Nepal’ was a protest against a proposed government partnership program to address, purportedly, Nepal’s ‘food security’. The program was to be implemented in collaboration with Monsanto, a biotech company with a notorious history of forcing farmers into death traps and plunging them to their deaths the world over, all in the name of ‘enhancing’ agricultural yield.

The campaign organized street protests, film screenings, radio shows as well as public discussion forums with journalists and policymakers. We also published essays and op-eds in news dailies and digital magazines. It was reassuring to see that there were readers for the writings and audiences for the events. Personally, that was the beginning of my ‘public’ writing as an occasional columnist. It felt like I had “found my voice”.

For the Ph.D., my next step was “to channel this newfound confidence into writing the dissertation”, as my advisor suggested. She was doing her job and I had to do mine. My voice had mattered to a constituency of people – writers, students, activists, journalists – in someplace. It was now my job to make the same voice matter to some other constituency – the Ph.D. committee, but also the wider academic community – in some other place. I cannot put my finger on how the channeling happened but it did. I found a way to preserve the confidence that the protest had lent to my voice, channel it to take ownership of the Ph.D., and somehow hoist it over the finishing line.

As a matter of self-learning, this is my final advice: Be open to the counter-intuitive possibility that events seemingly disconnected to a writing project may be harnessed to infuse new confidence into the writing process, as unanticipated as the possibility is at the outset. The ‘event’ does not have to be spectacular. It could be the sports you play every day in your neighborhood or friends that laugh at your quirky sense of humor. Own your voice as if it matters, which it does. Ignite the fire on the inside and vanquish the ghosts that block the road.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

17 min read

As the old year comes to an end and a new one begins, we look back on a year of Writing Journeys, reflecting on the diverse stories we've read and the great advice we've received.

Writing journeys

7 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, writer and editor Tenzin Dickie discusses writerly doubt and frustration, and drawing strength from good writing.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, engineer and political economist Dipak Gyawali pays tribute to the teachers who taught him to write precisely and meticulously.

Writing journeys

10 min read

Water expert Ajaya Dixit recounts his writing journey of learning to bridge the gap between the natural and social sciences.

Writing journeys

19 min read

Buddhisagar, one of Nepal's finest novelists, recounts how Karnali Blues came to be and offers writing lessons on discipline, authenticity and style.

Photo Essays

2 min read

How Durga Jirel’s business has been barely surviving through these uncertain times

Writing journeys

17 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson identifies 20 common mistakes Nepalis make in English and how to avoid them.

Perspectives

21 min read

Binod Bikram KC’s poems offer a sobering perspective on the times we live in