Writing journeys

10 MIN READ

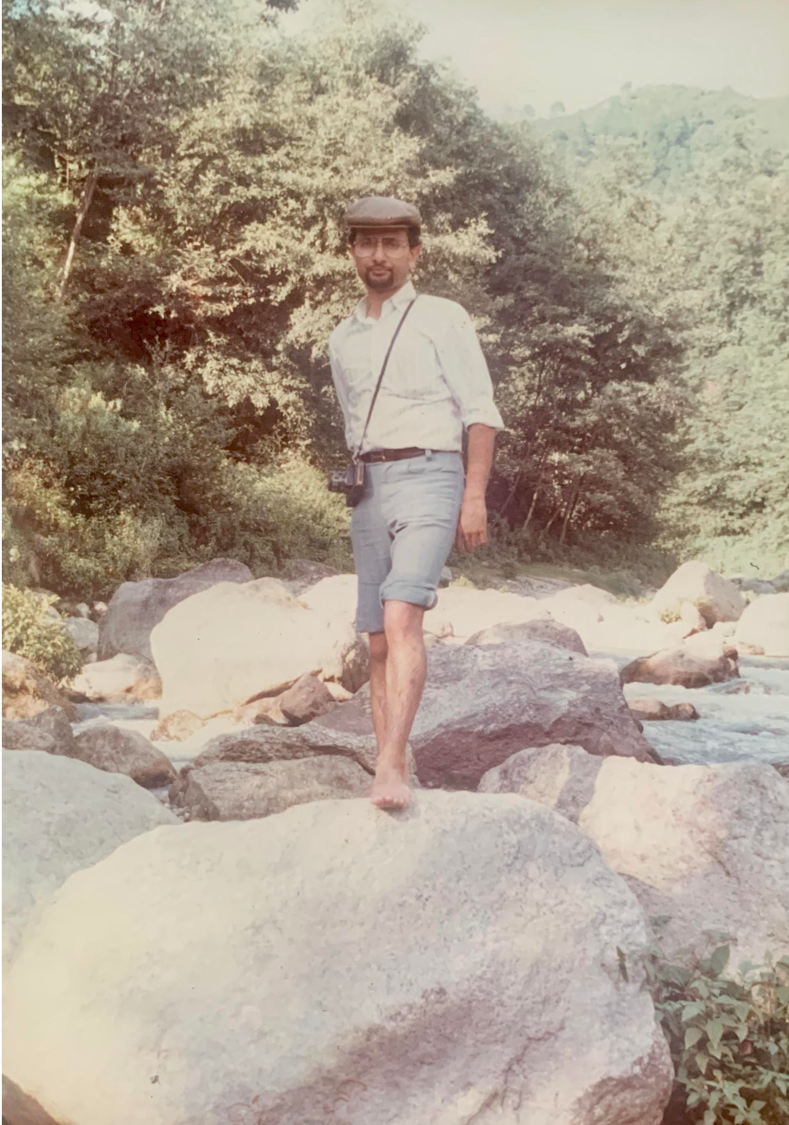

Water expert Ajaya Dixit recounts his writing journey of learning to bridge the gap between the natural and social sciences.

In Nepal, few people write more prolifically or persuasively about the absolutely crucial topic of water than Ajaya Dixit. In this Writing Journey essay, Ajaya ji describes his journey from an engineer focused narrowly on technical issues to one who sees that “water was not simply about equations but also about people, politics, and power.” He has made his life’s mission to bring the social and natural sciences together. “Improving water services,” he stresses with characteristic clarity and concreteness, is “much more than just designing pipes.”

Ajaya ji also describes his journey as a writer. He shares tips he picked up early in his career from American volunteers in Nepal. Drawing from his own writing routines, he emphasizes the power of revision and getting feedback from others (a common theme in this series). He also shares a wonderful piece of advice from the late Dr. Harka Gurung.

As you read, I hope you note that, in these essays, our contributors themselves use the writing pointers highlighted in the series. We walk our talk. Don’t miss the strategies that make Ajaya ji’s prose clear, concise, and engaging: lists, powerful quotations, short paragraphs, and colons. Nobody knows better than engineers the power of precision and the danger of extra moving parts.

I’d like to spotlight two of Ajaya’s excellent tips. First, reading drafts aloud. This is such a useful trick. The tongue and ear will catch mistakes that the eye flies over. And second, always remember the audience. While drafting, picture your reader in your head. Will they need more background? What jargon will they know and what will they need explained? How to lure them into the next paragraph? (For a great tip on thinking about audience, don’t miss Sujeev Shakya’s 'Shakespeare can be found in the fields of the Himalayan hills')

Finally, for other Writing Journeys that have also stressed the importance of good writing for engineers, see essays by Dipak Gyawali and Sonia Awale. For more on the need to broaden how engineers communicate, see my Republica essay ‘Engineering Nepal’s reconstruction’.

Thank you Ajaya ji. It was a joy working on this essay with you.

Ajaya Dixit studied at Regional Engineering College Rourkela, India (1977) and University of Strathclyde, Glasgow (1981). He lectured in water engineering at Nepal’s Institute of Engineering. His books include Basic Hydraulics (1987), Basic Water Science (2003), Dui Chimekiko Jalayatra (Water journey of two neighbors) (2008), Nepalmaa Bipad (Disasters in Nepal) (2016), Strengthening Policy Research: Role of Think Tank Initiative in South Asia (edited with Professor Sukhdeo Thorat and Samar Verma). He is a senior research advisor of Institute of Social and Environmental Transition. Since November 2020, Ajaya has been curating South Asia Nadi Sambad [South Asia River Dialogue] (soanas.org) an online platform that aims to foster greater dialogue and sharing of perspectives among sectors, disciplines, geographic regions, and generations about water.

***

Bridging the gap between natural and social sciences

I graduated as a civil engineer in 1977 and specialized in water science in 1981. Studying engineering in the 1970s did not require much writing. During my M.Sc. and subsequent teaching water science in Nepal’s Institute of Engineering, I began to write, mostly technical treatises. It was straightforward: state the objective, the methods, observations, discussions, and conclusions. It was a product meant for my own kind. From 1980 to 1990, the water world saw a major shift and I began to realize the limitations of my technical writings.

In 1980, the International Decade for Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation began and by the mid-1980s, it was clear that improving water services was much more than just designing pipes using scientific methods. Yet, I focused on the technical aspects, working on the draft of my first book Basic Hydraulics, published in 1987. I tried to explain the complexity of fluid mechanics using step-by-step clarifications, presenting the subject in simple and easy-to-understand language. It did not, however, include any of the social realities of our world as we deal with water.

I made frequent work-related travels to different parts of Nepal and realized that an engineering focus on water was necessary but incomplete without looking at its role in nature and its relationship with society. But I lacked the skill needed to weave these contexts together. In the mid-1980s, I also began working with the US Peace Corps as a part-time technical trainer on drinking water and irrigation system design and management. I discussed the difficulties I faced in linking natural and social aspects in my writing with some of the young Peace Corps volunteers, who had taken writing classes back home. They gave me simple suggestions: have a key message, get supporting evidence, and link the arguments in your writings. They further advised, “Write, write and write, revise, and if possible, avoid jargon.”

Slowly, I learned to include the social aspects of water and the environment in my writings on natural science, though these papers remained as ‘gray literature’ (unpublished reports). During this period, working with the late Dr. Harka Gurung opened up pathways to dealing with social and environmental concerns related to water. He once told me, “Ajaya, writing will give you an identity but also demands accountability. Your writings will remain with you for the rest of your life, and even after you are gone. Make sure you stand by them.” I did not understand what he meant then, but it became clear later on.

In 1990, as multiparty democracy was re-established in Nepal, the political atmosphere opened up. Gradually, new media outlets emerged for aspiring writers like me. Water challenges had become more serious: low access to basic drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene services; floods and inundation; droughts; lack of alternative livelihood opportunities; pollution; groundwater overdraft; and ecosystem degradation debates on in-country and transboundary water development. I was involved in studying and writing about most of them in the public domain.

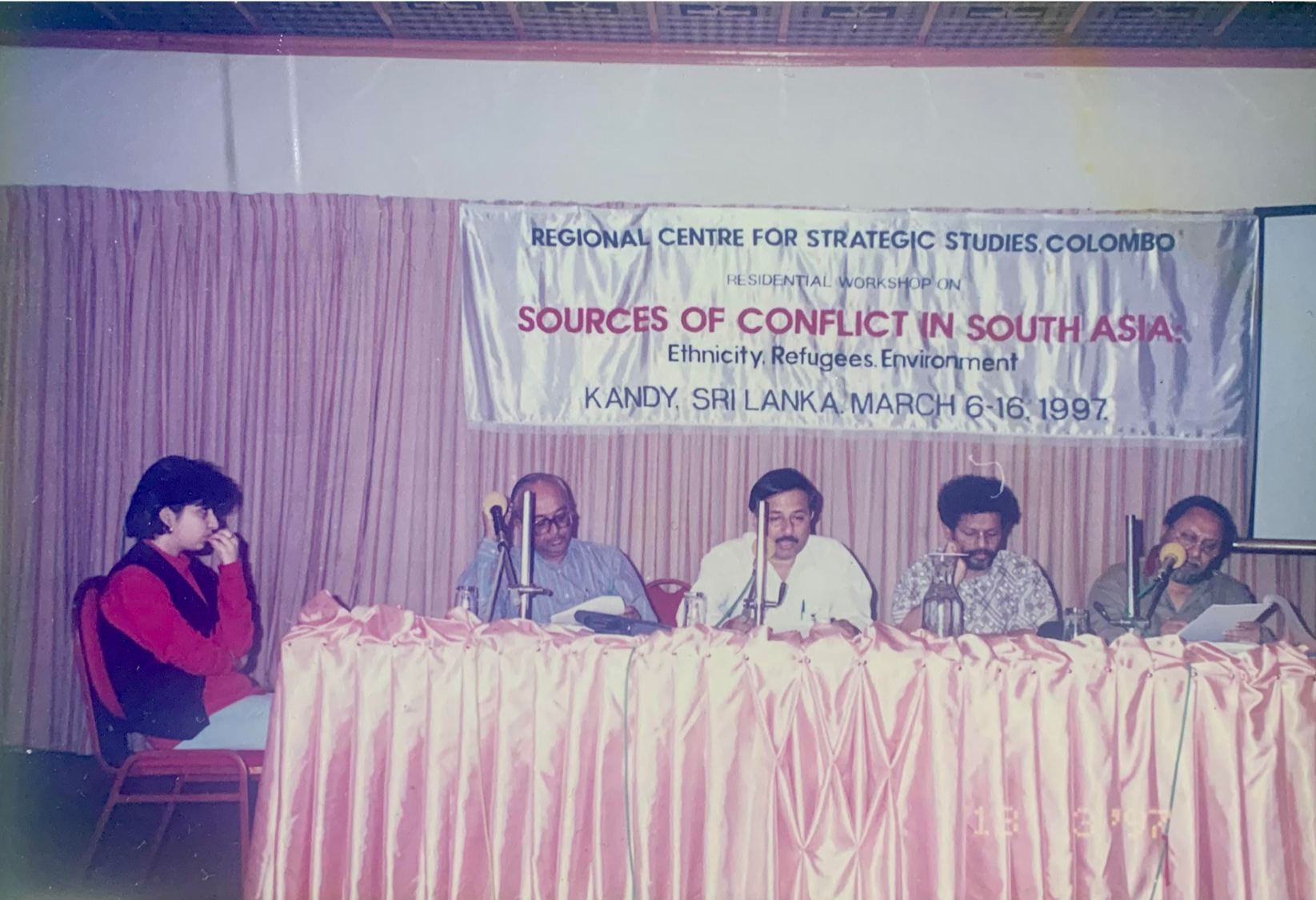

In the 90s, I had opportunities to interact with several policymakers, politicians, educationists, and civic society leaders across South Asia. I found a huge disconnect between the local-level realities and the big promises by policymakers. Gradually, I understood why. Most of the water plans were grand schemes, guided by the developmentalist state with total faith in science and technology. This made things easier for budget allocation and to present a narrative of development and growth. But it oversimplified complex local realities and was not able to deliver, particularly in places with poor governance. At the same time, the natural water science disciplines operated in silos. There was little or no conversation between the natural and social realms of water, at least in our part of the world. These problems persist even today.

I realized that I could work to improve conversations between those practicing the natural and social science disciplines. Interdisciplinary writings could link the two domains and inform public dialogue. For me, three agendas progressed in parallel. First, studying the intersections of the natural and social science of water. Second, learning the basics of sociology, law, economics, history, anthropology, as well as the natural ecosystem. Subsequently, I participated in regional research on water management, flood and droughts, food systems, engineering education, climate change adaptation, and public policy. And finally, writing in both Nepali and English by focusing on bringing the social and natural sciences together.

I try to reach a large audience through my writings, hoping that some of the ideas percolate to create changes in public discussions, policies, and practices. The suggestions by the young Peace Corps volunteer friends and Dr. Gurung gradually began to make sense. High-quality research, grounded on evidence and peer reviews, provided me with fodder for my stories. Water was not simply about equations but also about people, politics, and power. The exercise of power, mostly by the state, has led to widespread inefficiency, ecological degradation, and inequity in the way water was – and even today is – managed in South Asia. Socially marginalized families, women, and children still do not have access to basic drinking water and sanitation services. Aquatic biodiversity faces the threat of extinction and loss of dependent livelihoods. Social dislocation is high. My writings highlight these realities and call for more encompassing ways.

Today, I try to write every day. I go back to the text a few days later and revise. I read aloud what I write. I request other people to read my writings and provide me with feedback. The suggestions really help me see shortcomings in the text and revise them. I think of my audience and also of my peers while presenting my story. When I am satisfied with the draft, I send it for copy-editing. I find this process of iteration helpful and enjoyable. For new insights, I read a lot of books and materials from different disciplines.

The engineering discipline has a major role in shaping water and, when done well, engineering should provide services while maintaining environmental integrity. The rigor of an engineering education, particularly water engineering, helps students analyze an issue systematically and analytically. The discipline, however, has remained insulated and is not open to assimilating and accommodating other forms of knowledge. Engineering hubris is one of the factors that has grossly stressed our waterscapes. People and the climate crisis are worsening the level of stress. The impacts of climate change often manifest in the way built-water infrastructure performs (or, rather, does not perform) in South Asia, and has created more problems than it has solved. Increasing urban floods across the region is a prime example. In 2015, a study of 233 South Asian cities commissioned by the World Bank showed that floods accounted for 64 percent of urban economic loss over 20 years. Water engineers can, and must, do their bit to bring about much-needed shifts in the ways water is developed, managed, and governed.

One of my inspirations in this journey is Dr. Jayanta Bandyopadhaya, a friend and mentor. Educated as an engineer, Dr. Bandyopadhyay has transcended the confines of the discipline, questioning the technological determinism prevalent in the use of South Asia’s waterscape. He looks at water more from a holistic perspective than from a purely technical approach and is engaged in recrafting South Asia’s water knowledge in ways that are responsive to the specific character of the Himalaya region and local societies.

For a little over three decades, I have been teaching, studying, and writing on water, climate change, public policies, and disaster risk reduction. Over the years, I have encouraged and helped many junior colleagues in technical fields write about their work from an interdisciplinary perspective. I hope young water professionals will continue to tell their stories and offer new ways to reimagine water in nature, and for the people of South Asia.

In their stories, they must also weave in issues related to ecology, social impacts, sharing of benefits and risks, along with technical aspects such as size, height, cubic meters per second, MW, or hectares irrigated. Thus, water professionals can work with practitioners of social sciences as partners in their journey to a new balanced water future.

My storytelling will remain focused on the indivisibility and integrity of the water cycle as a key element of our re-imagined future.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

7 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, writer and editor Tenzin Dickie discusses writerly doubt and frustration, and drawing strength from good writing.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week in Writing Journeys, journalist and storyteller Chandrakishor writes about the value of learning new languages and using writing as a tool for social harmony.

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, US-based journalist and writer Sanjay Upadhya recounts his time working at The Rising Nepal under the Panchayat and the lessons he’s learned along the way.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Writing about disparate ideas like sustainable cities and food cultures, Prashanta Khanal has learned a lot and now, has a lot of advice to offer.

Perspectives

11 min read

The acceptance speech of writer Yogesh Raj who received the 2018/2019 Madan Puraskar for his historical fiction, Ranahaar.

Perspectives

7 min read

As a writer just starting out in publishing, Tim Gurung encounters harsh criticism and petty jealousy but that only emboldens him to push further.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week, series editor Tom Robertson provides a crucial tip on how to make your writing more effective and interesting — keep it short.

Writing journeys

11 min read

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.