Perspectives

Popular

Recommended

7 MIN READ

Commissioned by Mahendra, the image of Prithvi Narayan with his index finger raised perfectly encapsulated the Panchayat’s driving refrain of ‘ek raja, ek bhes, ek bhasa, ek desh’.

Today, January 11, marks the 300-year birth anniversary of Prithvi Narayan Shah, the man credited with the ‘unification’ of Nepal, long referred to as the “father of the nation”. But recent years have demanded a reassessment of Prithvi Narayan’s legacy and his ‘unification’ project, if it can be called that. Many now argue that Prithvi Narayan never set out to unify anything, as a large cohesive nation-state spanning the approximate length and breadth of modern Nepal had never previously existed. The region that is now Nepal was full of warring principalities and city-states, and Prithvi Narayan was simply a conqueror looking to expand his kingdom. Others, however, maintain that Prithvi Narayan’s project was one of nation-building.

The latter image – and intent – of Prithvi Narayan has been cemented in the collective consciousness through one striking portrait – the king, clad in a labeda-suruwal styled traditionally, his left hand clutching a sword, a shield strapped to his waist, a crown on his head, a tripundra tilak on his forehead, and his right hand raised in a now-iconic gesture – index finger pointing straight up at the sky.

This portrait, commissioned in the 60s by king Mahendra, is now the most widely circulated image of Prithvi Narayan Shah. It adorns stamps, government publications, school books, and even newspaper editorials. In the digital age, the portrait is regularly manipulated to suit specific contexts – sometimes, the raised index finger turns into a middle finger. The portrait has taken on mythic proportions, even though many might not realize its very recent provenance and the ideas that the portrait is meant to convey.

Mahendra believed in symbols, especially ones that would serve to unite his extremely diverse kingdom. When he embarked on his Panchayat experiment, he needed a suitable icon around which the entire country could rally. Coming straight out of the Rana regime, which had pretty much replaced all local iconography with those borrowed from the British and the Europeans, Mahendra needed something that was at once traditional yet modern, something that harkened back to a Nepal unspoiled by Rana excess and yet, was recognizable enough to the lay public.

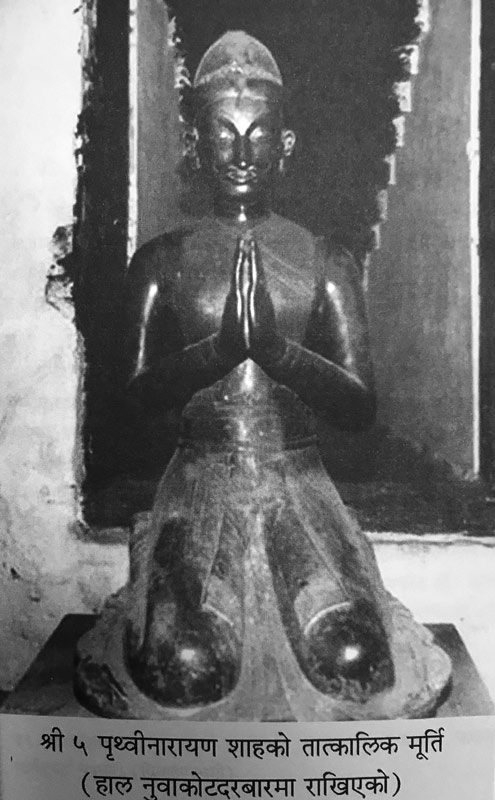

He called upon artist Amar Chitrakar, who consulted with a number of experts, including playwright and artist Bal Krishna Sama and historian Baburam Acharya, to draw up a portrait of Prithvi Narayan. Chitrakar had few images of Prithvi Narayan to draw from. According to ‘Remembering and Remaking Nepal’s Founder: A visual history of Prithvinarayan Shah’, a paper by Dannah Dennis and Avash Bhandari, the only extant image of the king from his reign is a black stone statue that shows him in a kneeling pose, his hands joined in prayer.

“In striking contrast to most of the later images of Prithvinarayan Shah, this statue lacks a khukuri knife, a shield, or any other visual clues meant to depict Shah as a conquering hero. In a way, here his masculinity is not as pronounced; rather he is subordinate to the authority of some divine being,” write the authors.

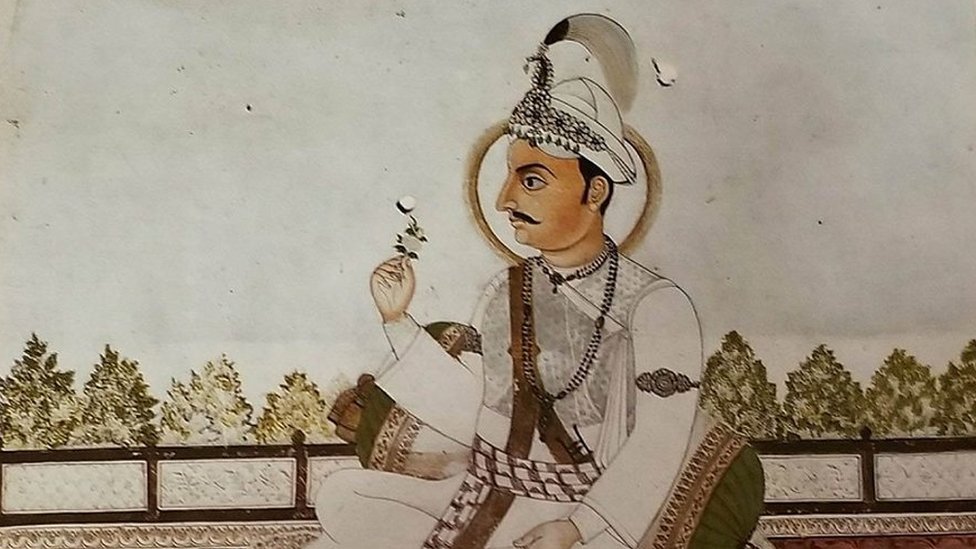

Later, during the reign of his grandson Rana Bahadur Shah, a Garhwali artist named Molaram is said to have arrived in Kathmandu and painted a miniature of Prithvi Narayan in the Persian-Mughal style. A Kantipur article calls this depiction the oldest portrait of Prithvi Narayan Shah and claims that it was painted during his reign by an unknown artist. The portrait presented in the article appears to be a reproduction of the miniature painted by Molaram, but not during Prithvi Narayan’s reign.

Chitrakar is believed to have based his portrait on this reproduction and by extension, Molaram’s miniature. This miniature showed the king in profile, holding a rose in his right hand with a nimbus around his head.

There are similarities between the two portraits and it is clear that Chitrakar drew upon the older one for much inspiration. The crown in both portraits is similar, so is Prithvi Narayan’s visage and his clothing. Chitrakar has even taken pains to include a similar armband on the left shoulder. But the departure is stark.

The most striking change is in Prithvi Narayan’s posture. In the earlier portrait, he is in profile, as was the prevalent style of the time. The painting is clearly inspired by Mughal-era art, where kings and royalty were often painted in profile, clutching a flower, a book, or handkerchief, as opposed to any objects of war. The depiction was usually of a softer side to the rulers. The portraits were meant to convey a genteel authority born out of genuine reverence for the king’s personality and policies, rather than brute force. The iconography of flowers harkens to poetry, the arts, and aesthetics; it shows that the king is also interested in matters other than that of war.

In stark contrast, Chitrakar’s portrait places Prithvi Narayan front and center, gazing directly at the viewer. It is more European in its style than Mughal, showing Prithvi Narayan standing tall, an active, virile, masculine depiction. Unlike the older portrait, the figure of the king is much more arresting and his masculine traits have been accentuated. His mustache is larger and more defined. The fat is all but gone from his face, except for under his chin, depicting a more angular, more stern visage. The eyes, even though they stare back, are lidded as if contemptuously gazing down at the adoring rabble.

Chitrakar’s portrait conveys strength and power, a strong king at the apex of his rule. It is also a heavily militaristic portrait, one that places great emphasis on the instruments of war. Prithvi Narayan’s sword and shield are prominent and his khukuri, perhaps the most iconic marker of Nepali bravery, is in the center of the frame, protruding large and ominous from the king’s patuka. Chitrakar has also done away with the nimbus (halo) around Prithvi Narayan’s head. The nimbus is often a marker of divine right, of godly descent, but Chitrakar’s Prithvi Narayan is a more human king.

The lasting legacy of Chitrakar’s portrait, of course, is the raised index finger, a gesture that has come to imply unity, a nation-state that is inviolable, however fragile that assertion might have been. By replacing the flower with the index finger, Chitrakar managed to sum up Mahendra’s aspirations in one simple gesture. That index figure elegantly encapsulated the Panchayat’s driving refrain of ‘ek raja, ek bhes, ek bhasa, ek desh’ (one king, one dress, one language, one country).

The portrait also propagates Prithvi Narayan’s, and Mahendra’s, attempts to establish Nepal as the ‘asali Hindustan’, the real land of the Hindus. As apocrypha has it, Prithvi Narayan believed that India had been corrupted by the influence of the Muslim Mughals and only Nepal remained untainted and pure as a Hindu heartland. In the Dibya Upadesh, he says, “But if everyone is alert, this will be a true Hindustan of the four jats, greater and lesser, with the thirty-six classes” (as translated by Ludwig Stiller in the book Prithwinarayan Shah in the light of Dibya Upadesh).

Whether Prithvi Narayan truly believed in Nepal as the only true land of the Hindus is still up for debate but for Mahendra, the Hindu identity of the modern Nepali state was paramount; after all, he was Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, earthly incarnation of the god Vishnu. So in Chitrakar’s portrait, Prithvi Narayan is a true Hindu Chhetri warrior. The tripundra tilak on his forehead marks him clearly as a Hindu and the necklace of pearls, in addition to the weapons of war, as a Chhetri.

The portrait thus not just asserts Prithvi Narayan’s place as the great unifier, the one who combined small squabbling kingdoms into one large nation-state, but also a particularly Hindu unifier. His policies vis-a-vis Capuchin missionaries or Muslim traders have little to do with his own identity as a Hindu king.

The Panchayat’s focus on one national identity turned out to be a disastrous experiment and Mahendra’s legacy, like Prithvi Narayan’s, is a complicated one. Mahendra inadvertently contributed, in no small part, to the downfall of his own house. The seeds of the Maoist conflict and Nepal eventually discarding the Shah monarchy were laid during the Panchayat.

But as an image of propaganda, the portrait of Prithvi Narayan Shah has perhaps no equal in Nepali history. This portrait allowed Mahendra to draw his own image, as progeny of the unifier, bulwark against outside forces, and protector of the Hindu character of the kingdom. The image served Mahendra’s purposes adroitly, as is evident in its lasting legacy even in the republican age.

Correction: Rana Bahadur Shah was Prithvi Narayan's grandson, not his son as originally stated.

Pranaya Sjb Rana Pranaya SJB Rana is editor of The Record. He has worked for The Kathmandu Post and Nepali Times.

Perspectives

11 min read

There is a lot for Kathmandu to learn from the Danish capital’s commitment to a culture of cycling

Features

9 min read

In a case eerily reminiscent of Nirmala Pant, 17-year-old Bhagrathi is believed to have been raped and murdered in Baitadi.

COVID19

News

5 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Opinions

4 min read

Supporting the Black Lives Matter movement goes hand in hand with actively dismantling the caste system

News

4 min read

Oli’s conspicuous silence on the recent Dalit lynching is disconcerting, to say the least

COVID19

Photo Essays

3 min read

Sumitra Bhujel has learned the value of adapting to technology and using the digital market to do business

Perspectives

4 min read

Cancel culture might embrace the postmodern ideas of freedom of expression and the plurality of truths but it also dismantles old truths to embrace new absolutes.