Books

9 MIN READ

Three new translations, one into English and two into Nepali, provide new opportunities for engagement across languages, cultures, histories, and contexts.

In her essay, ‘The Politics of Translation’, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak speaks of the act of reading itself as translation and translation itself as a form of reading. The politics of translation are such that they necessitate a “surrender of the self”, the inculcation of a deep and abiding love and affection for the text. This is especially important when the translation is that of a ‘feminist’ nature. “The task of the feminist translator,” writes Spivak, “is to consider language as a clue to the workings of gendered agency.”

As a translator herself, Spivak knows very well the trappings of interpretation. The translation is almost always a “shadow” of the original, but this is not to say that such a translation is always a diminutive. A ‘true’ translation is one that celebrates this relationship between the original and the translation, fully acknowledging that all of what is present in one might not always be present in the other. The accounting for this difference in rhetoric is the political act of translation.

Spivak writes, “The task of the translator is to facilitate this love between the original and its shadow, a love that permits fraying, holds the agency of the translator and the demands of her imagined or actual audience at bay. The politics of translation from a non-European woman's text too often suppresses this possibility because the translator cannot engage with, or cares insufficiently for, the rhetoricity of the original.”

One: On Muna Gurung’s translation of Sulochana

The latter admonishment is exactly what Muna Gurung avoids in her English translation of the Nepali poet Sulochana. In her translator’s note, Gurung speaks of the process of ‘accurately’ translating the Nepali poet Sulochana’s poems. Gurung writes, “Should I stay close to the source language and the poems’ forms, or should I move freely but stay true to the emotional heart of the poems as they travel from one language to another?” Gurung decides to stick close to the “vibe” of Sulochana’s poems and “the lives of these poems in this particular iteration”.

The result then is less of a translation and more of a conversation between the object and its shadow. ‘रहस्यमय रात’ (Rahasyamaya raat, literal: Mysterious night) becomes ‘Birth’ while ‘स्वामित्व’ (Swamitwa, lit. Ownership/possession) becomes ‘Property’, ‘नयाँ सपना देख्नलाई’ (Naya sapana dekhnalai, lit. To dream a new dream) becomes ‘Sleep (1)’. It is not just the titles that have changed; lines have excised and portions reformulated. These decisions do not appear to have been whims at the hands of a translator wielding the English language as a cudgel but rather, a careful carving of language by a skilled sculptor. Thus, even in translation, Sulochana’s poems bear the same heft that they do in the Nepali.

Sulochana’s poems, both in the original and in translation, might be written plainly but it would be a great disservice to call them simple. The poems, 32 of them in this new translation, are deceptive. They speak plainly but are inherently complex. Take, for instance, this translation:

The narrative thread in the original Nepali has been transformed into a haiku-like structure that is almost imagist in its evocative final line. In this structural transformation, the heart of the poem takes flight, alluding to an image that is inherent to the original, only emphasized by the translation. This is just one example of how Gurung engages with the “rhetoricity” of Sulochana’s poetry.

In other places, the metaphor is transformed. A ‘nanglo’ becomes a ‘sieve’. Whereas the former speaks, in Nepali, of spreading out on a surface, the latter implies a passing through. In Nepali, there is the act of picking through and selecting while in English, there is sieving and sifting. The two are not exact translations but they both work in tandem with each other. Read solely on their own, they appear to work independently but together, it is almost as if they are working in tandem, each building off the other.

Read either in the Nepali or the English, Sulochana’s poems themselves are about an internal reworking of the poems’ central metaphor: night. For the poet, night is not a place of darkness, fear, or danger but rather, silence, safety, and comfort. By embracing the darkness of the night, Sulochana rejects the dark-light binary. The night gives birth to the light, in much the same way that it gives birth to Sulochana herself and her writing. In one of my favorite poems from the collection, Sulochana (and Gurung) reappropriate the supposed violence of the night:

Gurung’s translation of Sulochana exemplifies the politics of translation, especially feminist translation, that Spivak writes about, especially since it is a translation from a minority language into the ‘hegemonic’ English. It might be a necessary task but it is one fraught with complications, albeit all of which have been handled adroitly by Gurung and Sulochana herself.

But how do these politics of translation play out when a text is translated out of the English into another language?

Two: On Bhrikuti Rai’s translation of Chimamanda Adichie

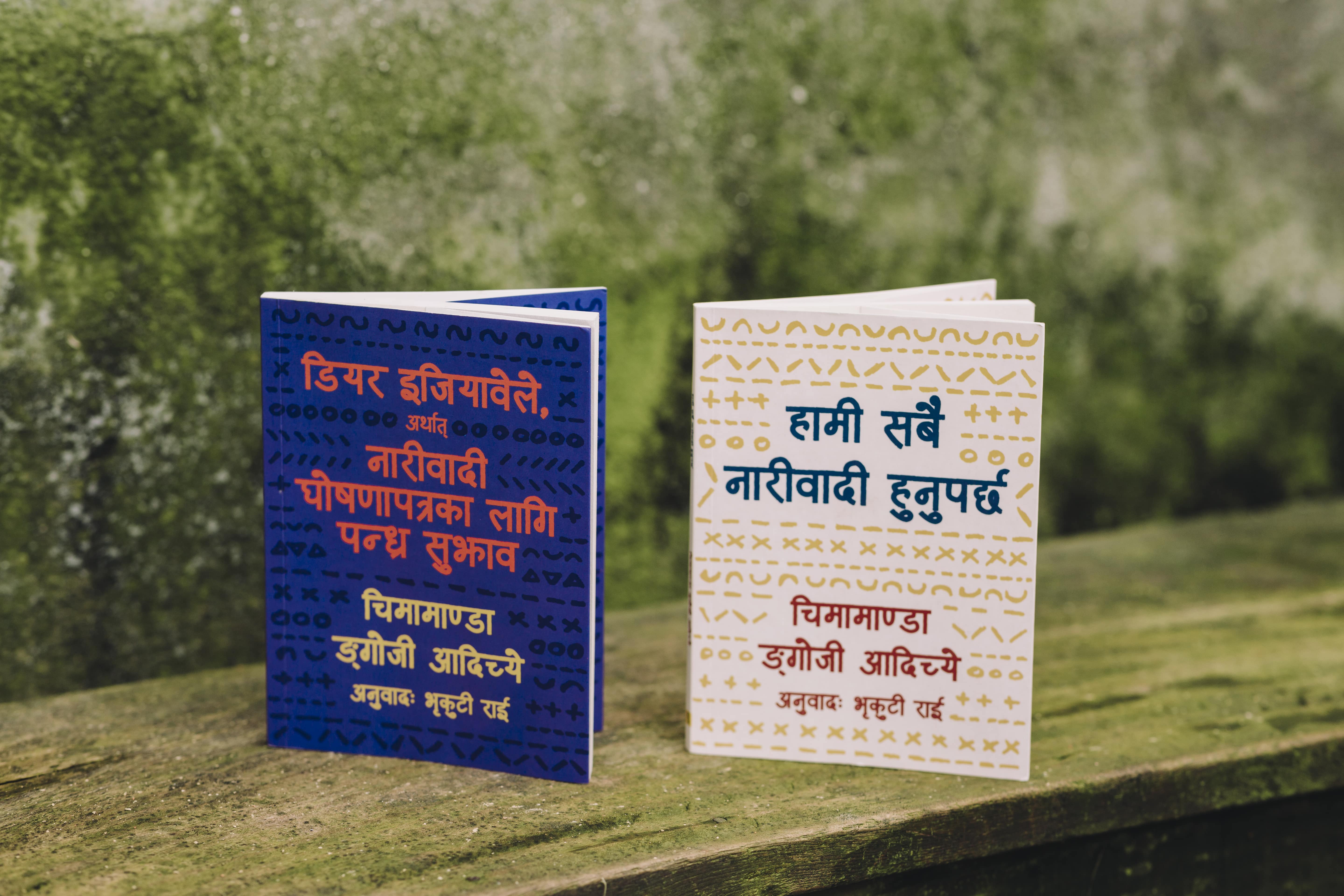

There are numerous interpretations at play in Bhrikuti Rai’s translations of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We should all be feminists and Dear Ijeawele. We should all be feminists was originally a TED talk, later adapted into a novella-length essay while Dear Ijeawele started out as a series of email correspondences with a friend regarding how to raise a feminist daughter. Adichie herself carried out part of the translation work and now Rai has picked up the baton.

While Spivak does not write of the politics of translating a work from English into other languages, it would be safe to surmise that this process itself is filled with pitfalls but can ultimately be a liberating experience. English is hegemonic in its usage and its history, as Adichie herself exemplifies. She, like her mentor Chinua Achebe, was born and raised in Nigeria and yet considers both English and Igbo her native languages. Achebe too wrote in English and was often criticized for it, most notably by Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong'o. But the very act of writing in English as a postcolonial subject can be transformative. The master’s language can be used against him.

Translation takes that opposition further. By taking literature out of English and into a language such as Nepali, the text now becomes inaccessible to those who only read English and much more accessible to those who read Nepali. The very act then becomes a process of decolonization, especially when the work being translated is an explicitly, unabashedly feminist work.

Many books of great political import have been translated into Nepali. Many of today’s politicians and intellectuals of a certain age and persuasion grew up reading Nepali translations of Soviet literature and propaganda. It is no wonder so many of them cite Maxim Gorky’s Mother as their favorite book. The political zeitgeist of the Cold War led to a flowering of Marxist thought in India and by proxy, Nepal. But in more recent times, books in translation have failed to capture the spirit of the era. Critical feminist theory has yet to make its way into the Nepali language in the same way Marxist thought did.

So Rai’s translations of Adichie, an African feminist, are especially important. The vaunted space once occupied by white Western feminists has slowly been ceded to women of color like Adichie. While a Nepali translation of Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex exists, it is perhaps just as critical that voices like Adichie also find some coherence with Nepali feminists.

Beyond just their polemics, these two books are innovative in their approach to feminism. Eschewing jargon, Adichie attempts to explain the necessity of feminism first in a moving personal speech and second, via letters. These forms themselves dictate that the work be less esoteric and more approachable. These are books meant for everyone, which is why they work so well in Nepali.

Rai’s translation is faithful to Adichie’s writing, taking few liberties with the language. Although, Rai does add a bit of local flair, employing dialect and colloquialisms to make the translation read less like a translation. In a conversation with Shilapatra’s Basanta Basnet, Rai expands on the nuances of translating a feminist text into a language that is inherently gendered. The tension between linguistics and semiotics is an eternal one and it is perhaps most evident in times of translation.

Both Gurung and Rai’s translations, although they go in opposite directions, are attempts to do what I quoted at the very beginning of this essay: to “consider language as a clue to the workings of gendered agency.” The translations, two in Nepali and one in English, explicate the complicated nuances of women’s agency as exemplified through language and if those nuances are able to make the leap from one language to another.

Both Sulochana and Adichie employ the craft of writing to lay bare the trappings of patriarchal thought and their own attempts, through writing, speaking, communicating, to break free. And through their translations, Gurung and Rai provide new opportunities for engagement across languages, countries, contexts, and histories.

***

Night, a translation of 32 of Sulochana’s poems by Muna Gurung, is being launched virtually on August 21. हामी सबै नारीवादी हुनुपर्छ (Hami sabai naribadi hunuparcha) and डियर इजियावेले अर्थात् नारी वादी घोषणापत्रका लागि पन्ध्र सुझाव (Dear Ijeawele, arthat naribadi ghosanapatra ka lagi pandhra sujhav), two translations of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s writings by Bhrikuti Rai, are being launched on August 28. The books are published by Safu, an imprint of Quixote's Cove, and are being launched in collaboration with KathaSatha as part of Women in Translation month.

Pranaya Sjb Rana Pranaya SJB Rana is editor of The Record. He has worked for The Kathmandu Post and Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

13 min read

Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson provides a list of easy tips on how to write better argumentative essays and opinion pieces for newspapers.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, Kunsaang narrates growing up in the mountains of Humla, studying from books that did not represent her, and writing to remember.

Writing journeys

6 min read

Introducing ‘Writing journeys’, a new series curated and edited by Tom Robertson where Nepali writers reflect on their non-fiction writing.

Books

5 min read

Set during the heart of the Gorkhaland Movement, the novella ‘Song of the Soil’ exhibits how revolutions are born in the minds of a few but built on the backs of thousands.

Perspectives

6 min read

In this new edition of Tim Gurung’s series on his life and times, he details the changing business climate in China and his eventual turn towards the literary world.

Writing journeys

17 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson identifies 20 common mistakes Nepalis make in English and how to avoid them.

Writing journeys

12 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, engineer and political economist Dipak Gyawali pays tribute to the teachers who taught him to write precisely and meticulously.

Writing journeys

7 min read

This week, The Record staff pick their favorite pieces of advice from the Writing Journeys series.