Writing journeys

12 MIN READ

Writing Journeys series editor Tom Robertson is back to identify eight common mistakes and provide Tom’s Twelve Tips on writing better sentences.

A month ago, I offered my favorite tips on essays (see ‘Excellent essays and Outstanding op-eds’). This week and the next, I will share some pointers on sentences. Some tips are basic, but some I didn’t learn until writing my PhD, such as to avoid ‘to be’ verbs. Most of these tips can be learned quickly, in just a few days. They can and should be taught in high school. Most importantly, they can transform your writing -- especially the pointers about verbs, wordiness, and abstraction.

In case you are wondering, I picked this title because one of my favorite aspects of Nepali language is the common use of reduplicatives, such as khaana-saana and bhaat-saat. I also think the tips in this article are super, handy, and easy.

Coming next week: 8 favorite sentences, with examples from Nepali writers.

8 Common Sentence Problems

Giving date and place at the end of the sentence (or not at all).

Weak verbs. They steal the life from your writing.

“To be” as main verb (is, are, was, were). Very common but easy to fix.

Passive voice/there is/there was. To be avoided.

Too many weak “and” sentences. Loose and unclear.

“Wordiness” -- too many unnecessary words. Tiring and boring!

Looooooong quotations. Boring!

Abstract vague language. A common disease among academics.

Tom’s Twelve Tips

#1 Put the date and place early.

Readers need this info right away. But a surprising number of writers either forget this info entirely or bury it late in the sentence or paragraph. Tell readers right away, especially if you are changing the time or place!

(For more examples, see Robertson, Transitions & Signposts sample essay)

#2 Find the people.

Wherever possible find the people in your sentence and write about them. In other words, write about people doing things, not big abstract nouns doing things. This will transform your writing. Find the people!

#3 Do a special round of editing just for verbs.

No word is more important to your sentence than the verb. Verbs are more important than nouns, adjectives, and adverbs. Write with verbs. Find the action in your sentence, then find a vigorous verb to express it. I suggest a special round of editing just for verbs. Re-read your draft, focusing just on verbs.

(For more on verbs, see the Vigorous Verbs Mitho Lekhai video, in Nepali.)

#4 Cut “to be” verbs as the main verb.

Most first drafts are packed full of ‘to be’ verbs as a main verb -- is, are, was, were. Non-native English speakers use a lot of ‘to be’ verbs as a main verb, but so do native speakers. I used to. When I learned this tip in graduate school, I saw big and quick improvements in my writing. Almost overnight, my prose became clearer, more concise, and more energetic. I was startled by how easy and powerful this suggestion was.

#5 Avoid passive voice and “there is” and “there are” sentences.

You hear this advice a lot. It’s actually not just a matter of style but a matter of content: passive sentences cut out the people doing the action, making it harder for readers to understand. “Mistakes were made” is in the passive voice. Government officials like to use the passive voice to avoid accountability. It doesn’t tell us who made the mistakes.

To be sure, sometimes the passive voice is appropriate and desirable. Many scientific journals use it (although fewer and fewer). Many newspapers use it when necessary to save space. The passive is also helpful to keep the focus on a certain subject, and it can better highlight victimization. Also, some may find the indirectness of the passive voice diplomatically advantageous. But in general, you can and should avoid the passive.

(For more on passive voice, see Vigorous Verbs Mitho Lekhai video, in Nepali.)

#6 Avoid weak ‘and’ sentences.

You can eliminate most weak ‘and’ sentences with stronger conjunctions (such as ‘because’ or ‘although’) or by splitting them into two shorter, more powerful sentences. Several weak ‘and’ sentences in a row make your writing very loose. Please note: this does not mean never use and! Just avoid it as a weak conjunction where possible.

#7 Put the most important words at the end of the sentence.

Doing so can add emphasis or drama to your writing. Here’s an example from Strunk and White’s famous book, The Elements of Style:

NO: Humanity has hardly advanced in fortitude since that time, though it has advanced in many other ways.

YES: Humanity, since that time, has advanced in many other ways, but it has hardly advanced in fortitude.

Check out this paragraph from one of my essays:

Historical detective work shows that almost all natural disasters are partly man-made. Hurricanes are a good example. Although a yearly occurrence generated by the energy collected in the Atlantic Ocean's tropical waters, the dramatic increase in carbon-spewing fossil fuel use over the last 150 years has fanned their fury. Global warming energizes the ocean water that transforms ordinary storms into monster storms.

(Source: Robertson, ‘Unnatural disasters’, Republica)

#8 Cut, Cut, Cut!

Perhaps the most important tip on this list. Nothing tires and bores readers more than unnecessary words. Make sure each word adds something new.

(For more advice on cutting, see Robertson, Less is More.)

#9. Learn paramedic editing.

Call in the writing paramedics! Paramedic editing is a set of quick rules -- a checklist -- to apply to your draft writing for easy improvement. It summarizes many of the tips in this essay. Just replacing ‘in’ and ‘of’ clauses (step #1) will make a big difference.

Example

In this example, note how “the writing of a report” became just “report writing.” Watch out for “of.”

(For more on paramedic editing, see this Purdue Owl page.)

#10 Trim loooooong quotations.

Quotations can be moving and powerful. They can add life to your prose. But long quotations are hard on readers. They are boring. The solution: It’s ok to cut unnecessary words at the beginning or end of quotations. A two- or three-word quotation is fine. In fact, Robertson emphasizes, “It’s good!” Effective and easy on readers.

(For more, see the Quality Quotations Mitho Lekhai video, in Nepali.)

Example

Long version: Robertson writes, “I think it’s good to trim down long quotations to short ones so that readers find it easier to navigate!”

Short version: Robertson writes, “It’s good!”

#11 Use parallel structure in lists.

‘Parallel’ here means consistent. Unparallel sentences are hard on readers, especially long unparallel sentences. Unfortunately, you see this easily avoidable mistake very often, in writing and in powerpoint slides. Parallel structure, like all these tips, should be taught in high school. Advanced tip: you can use parallel structure not just within a single sentence but also within a paragraph or even within essays.

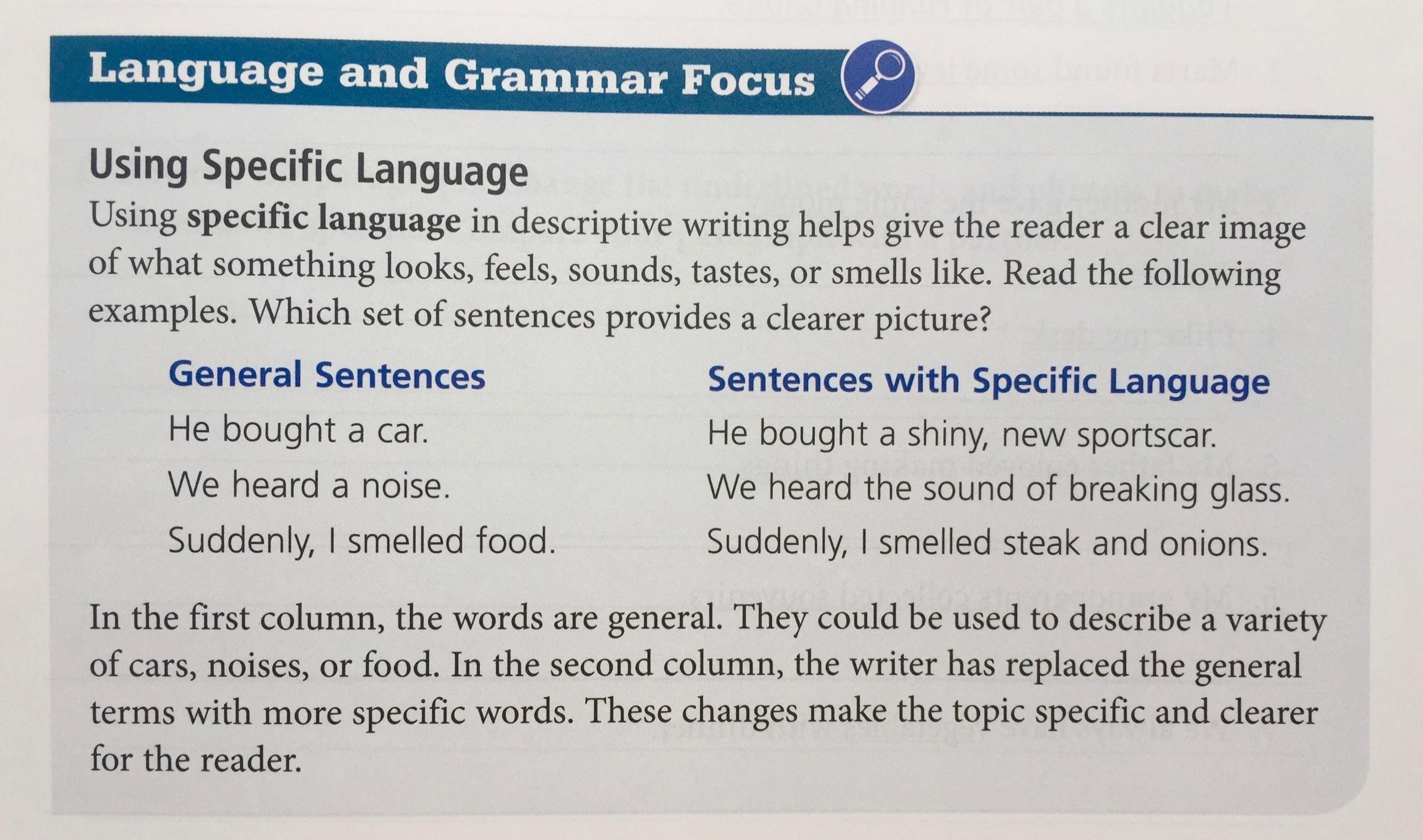

#12 Use precise, specific, concrete language -- avoid general, vague language.

Readers find vagueness hard to follow and abstraction hard to see. They find concrete language and examples much easier to grasp. My writing got much clearer once I figured this out. Re-read the writing tips in this article: my points get much clearer after I make them concrete with examples. It’s the same with most writing. The more concrete, the easier to read. See the examples below and you will get what I mean.

General, vague, abstract language is a common disease among academic writers.

Practice: How would you make these sentences more concrete and clear?

Nepal has a diverse population.

Nepal has a varied terrain.

Before 1990, Nepal had an autocratic government.

I remember exactly when I first learned this writing principle -- on a bright, cold January afternoon in Kathmandu in 1996, while I was struggling to find words for something in a graduate school application, not long after I had slurped sweet buffalo milk tea spiced with a little cardamom and was re-reading Stunk and White’s thin book on writing. After a little practice making my language concrete, my writing became infinitely clearer and more convincing.

A final note. I hope you find these pointers helpful. I know they work because I use them in every sentence I write. If you liked these tips, don’t forget last month’s suggestions for essays and op-eds.

***

If you want more examples and explanations about sentences, see the Mitho Lekhai Youtube video (in Nepali) on Super Sentences, click here.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Social science researcher Sabin Ninglekhu provides prudent useful advice when it comes to academic writing, especially the longer kind, in this week’s Writing Journey.

Perspectives

11 min read

The acceptance speech of writer Yogesh Raj who received the 2018/2019 Madan Puraskar for his historical fiction, Ranahaar.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week in Writing Journeys, Dhirendra Nalbo, researcher, academic, and educator, writes about the politics of language and how it affects the process of writing.

Writing journeys

8 min read

In another edition of Writing Journeys, advocate Dev Datta Joshi reflects on the difficulties of schooling as a visually impaired person and how he came to see writing as a transformative tool.

Writing journeys

25 min read

Do you know the verbs that experienced writers know and use routinely?

Writing journeys

6 min read

Introducing ‘Writing journeys’, a new series curated and edited by Tom Robertson where Nepali writers reflect on their non-fiction writing.

Books

Culture

11 min read

An 11-year-old reads six recently published children’s books and reviews them on her own terms.

Writing journeys

12 min read

Writing about disparate ideas like sustainable cities and food cultures, Prashanta Khanal has learned a lot and now, has a lot of advice to offer.