Perspectives

8 MIN READ

Connecting and improving green open spaces can provide exponential benefits for the people and the environment, and allow a suffocating Kathmandu to breathe freely.

Kathmandu needs a green necklace. As a series of linked water bodies, open spaces, parks, urban forests, and green streets, a green necklace would not only connect fragmented green spaces but also increase their ‘ecosystem services’— the benefits they provide humans, animals, and plants. When green spaces are connected, as in a necklace, the benefits increase exponentially.

Open spaces enhance the quality of life in any city. According to the World Economic Forum, access to green open space and a feeling of social connection creates livable and vibrant cities. Green open spaces provide a place to unwind and de-stress with friends and family, thereby improving social health. In particular, spending time in nature has curative powers. Phytoncides, an essential oil released by trees, are believed to have physical and mental health benefits. There is much research that shows that people living in urban spaces disconnected from nature face unnecessary stress. A lack of greenery in the city not only creates physiological but also psychological stress.

In Kathmandu, these stressors have multiplied ever since the city embarked on its environmentally unsound development. It’s haphazard, unplanned urbanization is sabotaging open spaces and greenery while leading to increases in air and noise pollution, temperatures, and flooding. Animal and bird habitats have been destroyed, robbing the city of any urban wildlife. Citizens are even unable to walk around their city, grossly limiting their interactions with the spaces around them and their neighbors. Rushed, haphazard development has sapped the life from the city.

For a Kathmandu that is suffocating from its own emissions, such interconnected green spaces are crucial for the wellbeing of its people.

Kathmandu’s green infrastructure

Many Kathmandu residents have realized the ecological, religious, cultural, and disaster relief services of open spaces. Vijaya Shrestha, coordinator of the Occupy Tundikhel campaign, organized the movement “to tell the masses how our open spaces are being encroached upon and why they should be preserved.”

To protect and maximize the benefits from nature, we need to identify, develop, and connect the few green spaces that remain.

The Kathmandu Valley Development Authority has identified 887 open spaces within the Kathmandu Valley: 488 sites in Kathmandu, 345 in Lalitpur, and 53 in Bhaktapur. Among these open spaces, 58 percent of land totaling 17,750 ropanies is usable for public activities. These open spaces vary in size, services, and function — from the three Durbar Squares and Tundikhel to residential courtyards and green pockets like Rani Bari.

But identifying open spaces alone cannot guarantee their protection; they need to be developed and owned by communities, organizations, and governments. Ownership fosters a feeling of belongingness that encourages people to take care of their parks.

Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) has thus started developing 36 parks of varying sizes and services. It is currently collaborating with 11 municipalities to develop other green spaces around the valley.

However, sustainable management of parks and open spaces face many challenges: unclear ownership, lack of belongingness by the community, poor maintenance, widespread commercialization, and encroachment by organizations and individuals.

In some cases, open space development has turned into ‘bourgeois environmentalism’ where high boundary walls, restricted opening times, and entrance fees cordon off public spaces for those who can afford it. This deprives ordinary people from green benefits. The city must provide equitable distribution to accessible nature.

Fragmented to connected greens

The valley’s open spaces are fragmented -- unplanned urbanization has left behind disconnected patches of natural habitats. Due to such a fragmented ecology, wild animals are frequently encountered in the peri-urban areas. According to Environment Science Professor Narayan Koju, “broken bio-corridors” are what is causing repeated leopard-human interactions in the Valley. Ecological corridors not only help plants and animals spread and migrate, but also recolonize environments disturbed by fire and flood. Therefore, these corridors reduce the consequences of habitat fragmentation.

In cities, ecological corridors also provide a continuous shaded path connecting urban amenities like theaters, universities, libraries, shopping malls, and offices with parks and water bodies — improving walkability. Creating corridors can ultimately develop a green necklace for the city.

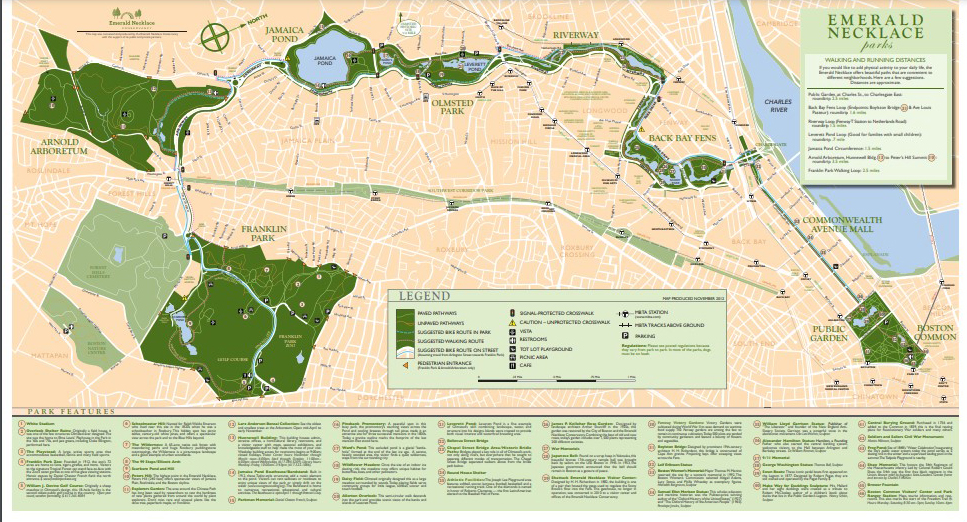

No place shows the benefits of connecting green spaces better than Boston’s famous Emerald Necklace. Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1880s, the Emerald Necklace is a 11-km-long sequence of waterways, six parks, an arboretum, a zoo, and green streets. Unlike unconnected urban parks, Boston’s emerald necklace connects open spaces, recreation, and flood control. Today, the connected green space is enjoyed by Bostonians and tourists alike for strolling, sunbathing, cycling, bird watching, sailing, hiking, playing golf, and learning about plants and animals.

Can Kathmandu create a green necklace?

The shrinking of Kathmandu’s open spaces are not only due to encroachment but also a lack of clear policies. The 2017 National Urban Development Strategy identified “poor governance” and “fragmented policies and regulations” as the primary causes of this shrinking. The dire situation demands three major actions -- a clear policy on open space; plans and projects that incorporate nature; and more green spaces.

Creating a green necklace for Kathmandu requires political buy-in and support from various stakeholders. Unfortunately, politicians are generally attracted to short-term infrastructure projects that are visible and tangible enough to win votes. Basically, they don’t have the patience to watch a tree grow. And for many residents who have lost hope of any significant progress in the city, a green necklace might seem too ambitious.

I agree. Looking at the poor condition of the city’s parks and river corridors, a green necklace can seem overwhelming. It demands time and effort.

But Kathmandu can learn from the restoration of Seoul’s CheongGyeCheon River, where a six-lane highway over the river was destroyed to create a green belt with a waterfront. Similarly, Boston’s Charles River and its surroundings were re-designed to create a wilderness out of tidal flats and floodplains fouled by sewage and industrial effluent.

Kathmandu’s river corridors have been designed purely for vehicular traffic. However, we can develop river banks as green corridors, which would also help reduce flooding. Spring’s colorful flower blossoms along the river corridor show what’s possible.

Likewise, Kathmandu’s Ring Road and major road networks can create and connect green spaces. Tree-lined streetscapes will create an ecological corridor, providing a continuous shaded path to the urban population, and a movement corridor for birds, insects, and small creatures. Greenery along the street can reduce stormwater runoff, heat, air, and noise pollution, ultimately reducing the havoc of climate change.

Similarly, small gardens in schools and residential neighborhoods could be used as a stepping stone to achieve the green necklace. The government’s green school program, if implemented, can promote and preserve the local biodiversity.

Accessible green

Cities around the world are greening their landscapes by de-paving hard spaces, developing parks and riverfronts, adding greenery to streets, encouraging gardening in schools and residential neighborhoods, and preserving urban forests. Kathmandu should follow suit. More importantly, Kathmandu needs to connect the few green spaces that exist.

Technically, connecting these spaces is possible. The bigger challenge is social and political will. Kathmandu's public and politicians need to better appreciate the benefits of green spaces. Above all, the city’s environment department should stand strong against development that comes at the cost of the environment.

Greenery should be woven into the city’s fabric, rather than seen as just an ornamental addition. People in Kathmandu -- especially the elderly and children -- should be able to enjoy strolling, jogging, playing and hiking in nature, listening to birds, reading books in the shade, and enjoying the sun on fresh green grass. Most importantly, they should be able to breathe fresh air.

Nilima Thapa Shrestha Thapa Shrestha is an architect and urban planner mostly focused on urban environmental planning and disaster risk reduction.

Features

4 min read

Bats, chiuri trees, and the Chepang community make up a unique ecosystem in the Chure region that is now coming under threat.

Features

10 min read

Reservoir-type hydropower projects might generate much-needed electricity for Nepal but they also come at significant environmental, ecological, and social costs.

Features

5 min read

Research paper led by a Nepali author explains the rare phenomenon of 'leucism' in two krait species

Explainers

7 min read

Four Nepalis were recently arrested in possession of uranium. The Record explains what they were planning to do with it and how much it’s worth.

Perspectives

4 min read

In two weeks, the birds taught me many things: to be compassionate, to be kind, to be angry even. But most of all, to love with patience.

Perspectives

11 min read

The most significant international climate event since the Paris Accord is two days away. For Nepal, its citizens’ lives and its long-term development trajectory are at stake.

COVID19

News

4 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Perspectives

6 min read

Our urgent need for a second international airport must be balanced with legitimate environment concerns