Photo Essays

Features

16 MIN READ

Retired British General Sam Cowan recounts the times he spent with five Gurkha Victoria Cross holders from the Second World War.

This photo essay has its origin in a Facebook post first put online two years ago. I reposted it recently to mark the 75th anniversary of VJ Day, and a number of friends contacted me to say that it deserved a more lasting home than the brief transience of a Facebook post.

The 75th anniversary of VJ Day, which marked the surrender of Japan and the end of the Second World War, fell on August 15, 2020. In July 1995, five surviving Gurkha Victoria Cross holders from the Second World War, all of whom had taken part in the war against the Japanese in Burma, arrived in the UK as guests of the UK government, to take part in the 50th anniversary celebrations. Each was permitted to bring a family member as a minder. I was Inspector General of Army Training at the time and occupied a large defence ministry house on Salisbury Plain. As Colonel Commandant of the Brigade of Gurkhas, I had the privilege, with Anne, of hosting the party as our family guests for three nights. The photo above was taken shortly after they had arrived. Seated from the left are Lachhiman Gurung, Gaje Ghale, Ganju Lama, Bhanbhagta Gurung, and Agansingh Rai.

On the first evening, we took them to the small village pub, where they interacted with the locals as if they had been born and brought up in the village. Extracting them from the pub was a major challenge, as was getting them to bed. It was the first of three long nights — and early mornings — as they insisted, as was their custom at home, on rising with the sun. It was mid-summer! On the final evening, we hosted a reception for 100 people who had contributed generously to the Gurkha Welfare Trust for the privilege of meeting and chatting with the VC veterans after a Beating Retreat on the tennis court by the pipes and drums of the recently formed 3rd Battalion, The Royal Gurkha Rifles (formerly 10th Gurkha Rifles). Friends who attended still talk about it. On the second evening, we had a dinner for them at home, as this photo shows.

Lacchiman Gurung was born on 30 Dec 1917 in the village of Dakhani, in Tanahun District, Nepal. He joined the army in December 1940, even though at 4ft 11in, he was below the minimum height for enlistment. As a Rifleman in the 4th Battalion, 8th Gurkha Rifles, in Burma, on 14/15 May 1945, he was manning the most forward post of his platoon which bore the brunt of an attack by at least 200 of the Japanese enemy. Twice he hurled back grenades which had fallen on his trench, but the third exploded in his right hand, blowing off his fingers, shattering his arm, and severely wounding him in the face, body, and right leg. His two comrades were also badly wounded, but he loaded and fired his rifle with his left hand for four hours, calmly waiting for each attack, which he met with fire at point-blank range. To quote from his citation: “Of the 87 enemy dead counted in the immediate vicinity of the Company locality, 31 lay in front of this Rifleman's section, the key to the whole position.” Lachhiman retired from the army in 1947 and returned to Nepal. He died on 12 Dec 2010.

Gaje Ghale was born on 1 August 1918 in Barpak Village in Gorkha District, Nepal. He enlisted in the army as a boy soldier in 1934. On 25 May 1943, he was a 22-year-old Havildar (Sergeant) and a platoon commander in the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, when his battalion attacked a strong enemy position in the Chin Hills in Burma. Gaje’s platoon was in the van. While they were preparing to attack, the van came under heavy mortar fire, but he rallied his men and led them forward. They soon faced withering defensive fire, and Gaje was wounded in the arm, chest, and leg by a Japanese grenade. Paying no heed either to his wounds or the intensity of Japanese fire, he closed with the enemy and a bitter hand-to-hand fighting ensued, which is best described in the words of the citation for his VC: “Havildar Gaji Ghale dominated the fight by his outstanding example, dauntless courage and superb leadership. Hurling hand grenades and covered in blood from his own neglected wounds, he led assault after assault encouraging his men by shouting the Gurkha battle-cry 'Ayo Gurkhali' (‘The Gurkhas are upon you'). Spurred on by the irresistible will of their leader to win, the platoon stormed and carried the hill by a magnificent effort and inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese.”

Together with his battalion, Gaje transferred to the Indian Army in 1947. After a distinguished further career, in which he reached the rank of Subedar Major, he was granted the rank of Honorary Captain on retirement. In his retirement, he lived in Almora, Uttar Pradesh. He died on 28 March 2000.

Ganju Lama was born on 22 July 1924 in Sangmo in southern Sikkim, situated 6km away from the sub-district headquarters of Ravong. As a Sikkimese citizen he was not entitled to be recruited as a Gurkha but in war time the rules were flexibly interpreted and he was recruited on 24 July 1942. He had just turned 18. His name was Gyamtso Shangderpa, but a clerk in the recruiting office wrote it down as Ganju, and the name stuck.

After six months of basic training at the 7th Gurkha Regimental Centre at Palampur in the Punjab, he was included in a reinforcement party of 180 soldiers for the 1/7th Gurkha Rifles in Burma. On the night of 16 May 1944, the advance of the battalion’s B Company was held up by three Japanese tanks at Milestone 33 on the Imphal-Tidim Road. Ganju was No 1 on the PIAT gun, a man-portable anti-tank weapon which was only effective against Japanese tanks from close range. Under heavy fire Ganju crawled towards the tanks and skilfully destroyed two of them with his PIAT gun. Despite being wounded he held his position and managed to kill the crews as they tried to escape by lobbing hand grenades at them. He was evacuated to get his wounds dressed. For his bravery in this action, Ganju was subsequently awarded a Military Medal, which is given for, "acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire".

Just three weeks later, on the night of 12 June 1944, the battalion faced an exceptionally strong Japanese attack. After ferocious hand-to-hand fighting, and supported by three medium tanks, the enemy broke through the line in one place, pinning opposing British troops to the ground with intense fire. Ganju’s company was ordered to counter-attack and restore the situation. Shortly after passing the start line, the company came under heavy enemy medium machine-gun and tank machine-gun fire at point-blank range, which covered all lines of approach. Ganju, the No 1 on the PIAT, crawled forward through thick mud, bleeding profusely, and engaged the tanks single-handedly. In spite of a broken left wrist and two other wounds, one in his right hand and one in his leg, caused by withering cross-fire concentrated on him, he succeeded in bringing his gun into action within 30 yards of the enemy tanks. He knocked out the first one, and then another, the third tank being destroyed by an anti-tank gun. Despite his serious wounds, he then moved forwards and engaged with grenades the tank crews who were now attempting to escape. Not until he had killed or wounded them all, thus enabling his company to push forward, did he allow himself to be taken back to the Regimental Aid Post. His citation for the VC concludes: “it was solely do to with his prompt action and brave conduct that a most critical situation was averted, all positions regained and very heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy.”

Ganju’s wounds were so severe that he was evacuated into the medical support system in India. In early October 1944 when news came through about the award of the VC no one knew exactly where he was in the hospital system in India. He was eventually traced to a hospital in Lucknow. What happened next is best related in Ganju’s words. “Suddenly one day, there came to my ward, lots of senior officers with red tabs. They were all smiling and wanting to shake my hand. They kept telling me I had won a medal – the Victoria Cross. Well, I was only a simple illiterate hillman then and had no idea what the Victoria Cross ‘thing’ was. Anyway, it was all rather good. The nurses and everyone fussed over me and I was upgraded to a better officer’s ward. Later I was moved to Delhi.”

Ganju received his Victoria Cross and Military Medal at an investiture held at the Red Fort in Delhi on 24 Oct 1944. At the ceremony, he was wheeled forward in a wheelchair by an orderly who was met halfway by General Bill Slim who took over and pushed Ganju up to the Viceroy, Lord Wavell. Ganju was able to stand up for the award. He was then wheeled away by the orderly to the side of the saluting base. Ganju later recorded that he was particularly proud that his own General from Burma was present and had pushed his wheelchair up to the Viceroy. What a great but very typical gesture from one of Britain’s greatest, and most loved and respected, senior Generals!

Ganju spent the next 20 months being moved round various hospitals in India. Even after he returned to his battalion, he was placed on restricted duties. At some stage towards the end of this period, Ganju was able to take some well earned home leave. The invitation below gives the context for the next significant event in his life.

In 1946, Captain M. Epstein was a War Emergency Commissioned officer in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He is now Professor Sir Anthony Epstein CBE, FRS, a world renowned virologist, aged 100, and still going strong. I am most grateful to him for sharing, and giving me permission to use, the image above and the two photos which follow. They remain his copyright. I am also grateful to my friend Ed Douglas for putting me in touch with Sir Anthony.

Immediately after the war, the then Captain Epstein walked through the Kumaon Himalaya from Almora to Milam and back. He also visited Sikkim on several occasions where he stayed at The Residency with Arthur Hopkinson CIE ICS, the British Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet. Political officers were in charge of overseeing the British Empire’s interests in the region and its relations with Tibet and the Himalayan kingdoms of Sikkim and Bhutan. The White Memorial Hall mentioned in the invitation commemorates the formidable John Claude White who was the first British political officer in Sikkim from 1890 to 1908. Hopkinson was the twenty second and the last one.

At the Garden Party on 19 Dec 1949, the then Captain M Epstein was able to take this historic photo

The length of Ganju’s hair in this photo, compared to how it looked at the VC investiture, for example, indicates that at the time he was on a period of prolonged and well deserved home leave. He was still a Rifleman at the time. His promotion to Naik [Corporal] came a few months later.

Arthur Atkinson had seen active service in the First World War. After joining the Indian Civil Service, he served in many interesting places along British India’s northern frontier. He had arrived in Gangtok in June 1945. He was asked by the Government of India to continue for a year after Independence as the First ‘Indian’ Political Officer. He handed over to Harishwar Dayal ICS on 1 Sep 1948. Up to 16 May 1975, ten Indian political officers followed Hopkinson. The facts of what happened and how it happened are disputed but on the previous day,15 May 1975, the Indian President, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, ratified a constitutional amendment that made Sikkim the 22nd state of India and abolished the position of the Chogyal.

I have given that short background because I think one can see, in the speech Sir Tashi Namgyal gave at the garden party, hints of concern, that the measure of independence Sikkim enjoyed under the British could be at risk after the British departure. Here is the speech: you can judge for yourself.

This speech established Ganju as a Sikkimese national hero. Sir Tashi Nymgyal died in 1963 but Ganju was further honoured in 1966 by the 15th and last Chogyal of the Namgyal dynasty of Sikkim, Palden Thondup Namgyal,by being conferred with the title PEMA-DORJI as a personal distinction. I know from his writing that this was an honour that Ganju particularly cherished.

After India's Independence in 1947, Ganju joined the 11th Gorkha Rifles, a regiment comprising men of the 7th and 10th Gurkha Rifles who had elected to continue their service with the Indian army. Later promoted to Subedar Major, he was made an honorary captain in 1968, while still serving, and on his retirement to Sikkim in 1972, he was appointed ADC to the Indian president for life. He died on 1 July 2000.

As explained above, Sikkim became part of India in 1975 but as this screenshot from “SikkimNOW”, dated 2 Nov 2013, shows, Ganju continues to be honoured in Sikkim to this day..

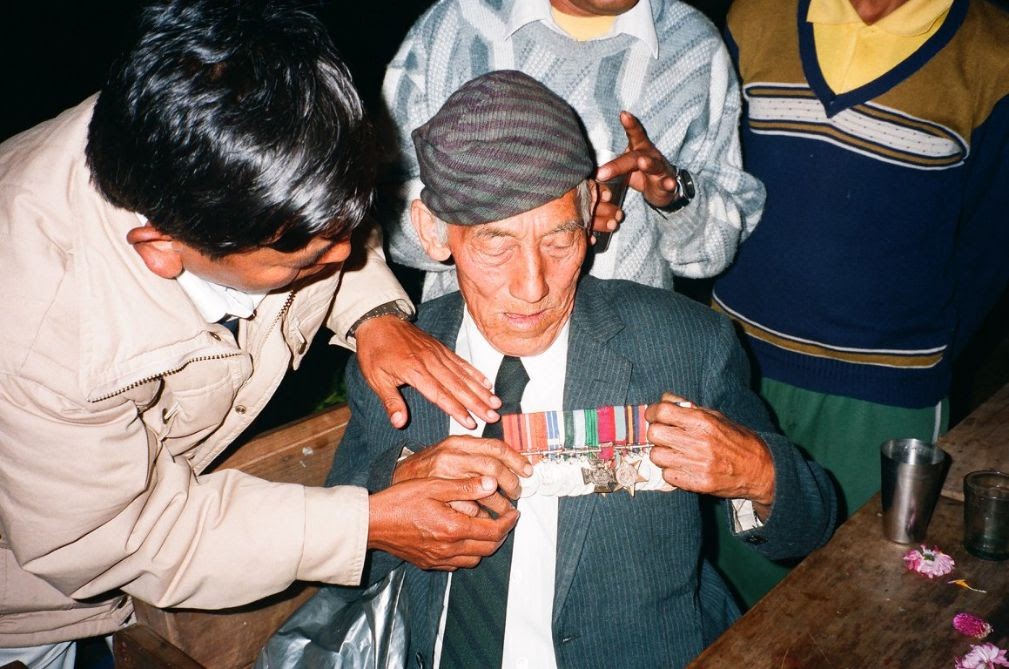

I first met Bhanbhagta Gurung when trekking near his village of Phalpu, north of Gorkha in 1992. When we met again in UK in 1995, I saw immediately that he was a totally different man because of very severe head injuries which he suffered when he had a fall from a roof two years previously. The next photos from 1992 better capture the strong and forceful character of the man which was amply demonstrated in the extraordinary actions for which he was awarded the VC.

Sitting beside Bhanbhagta is Captain Gambahadur Budhaja, who was my trekking companion. Our guide was a corporal from the local area who was home on leave. We camped above Bhanbhagta’s village, though I had no idea of that when we’d arrived in the place. After we finished our evening meal, obviously carefully pre-arranged, Bhanbhagta appeared out of the gloom. A long night was soon to begin!

Bhanbhagta was born in Phalpu in September 1921. On 5 March 1945, as a Rifleman in the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Rifles, his company attacked a Japanese defensive position but were pinned down by heavy fire. Without waiting for orders, Bhanbhagta dashed out to attack the first enemy fox-hole. Throwing two grenades, he killed the two occupants and without any hesitation rushed on to the next enemy fox-hole and killed the Japanese in it, with his bayonet. He cleared two further fox-holes with his bayonet and grenades. "During his single-handed attacks on these four enemy fox-holes, Bhanbhagta was subjected to almost continuous and point-blank light machine-gun fire from a bunker on the North tip of the objective. Again, he went forward alone in the face of heavy enemy fire to knock out this position. He doubled forward and leapt onto the roof of the bunker from where, his hand grenades being finished, he flung two No. 77 smoke grenades into the bunker slit. He killed two Japanese soldiers who ran out of the bunker, with his kukri, and then advanced into the cramped bunker and killed the remaining Japanese soldier. He retired from the army in 1947 and returned to his village. He died on 1 Mar 2008.

Fifty years later the smile was still strong!! After a few drinks, and a half hour chat, Bhanbhagta clapped his hands, shouted out a few orders and villagers started to appear out of the darkness, all ready for the party!

Cheerful and happy! All waiting for the action to start. As the following photos indicate, a long evening ensued. We were on a trek which was more of a forced march, and I wanted to retire to my tent early, but the sheer force of Bhanbhagta’s personality kept me going to the end to properly and generously reward the performers!

Soon it was time for everyone to get into the action, including me and my porters, but Bhanbhagta was the main man. He was unstoppable, though periodically he would stop proceedings to make short speeches, which were far too complimentary to the visitors, to repeat!

This is a view of Bhanbhagta’s village taken the morning after the night before! The path down to the village can be seen on the left. When we parted at a very late hour, the great man assured me that he would come up to the campsite to say goodbye, no matter how early we left! A few villagers did arrive to see us off, but Bhanbhagta, very sensibly, was having a much deserved lie-in.

Agansingh was born on 24 April 1920 in the village of Amsara, in Okhaldhunga District, just above Rumjatar. On 26 June 1944, he was a 24-year-old Naik (Corporal) in charge of a section of 10 men in the 2nd Battalion, 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, when he led his section in an attack on one of two posts which had been taken by the enemy and were threatening the British forces' communications near the town of Bishenpur in the state of Manipur. Under withering fire, Agansingh and his section charged a machine-gun. He himself killed three of the crew. When the first position had been taken, he then led a dash on a machine-gun firing from the jungle, where he killed three of the crew, his men accounting for the rest. He subsequently tackled an isolated bunker, single-handed, killing all four occupants. The enemy were now so demoralised that they fled, and the second post was recaptured. He transferred with his battalion to the Indian Army in 1947 and later achieved the rank of Honorary Captain before retiring to his village in Nepal. He died on 27 May 2000.

In November 1994, Anne and I trekked across a chunk of east Nepal in 11 days, from Hile to Jiri, visiting the Gurkha Welfare Centres of the Gurkha Welfare Trust at Bhojpur, Dikel, and Rumjatar, and taking the long way out via Solu. I was Chairman of the Trust at the time. On arrival at Rumjatar, we met Agansingh, who continued to live in his small village above Rumjatar and had come down to the Centre to greet us. Agansingh was a quiet, very impressive man, and an absolute delight to know. Talking to us that afternoon in Rumjatar, he explained that when he attacked the final position, he was the only man in his section still standing. The others had either been killed or were well behind him on the ground, seriously wounded. The enemy fire was so intense that early on in the attack he had given himself up for dead. He told me, “I decided that I was a dead man; there was no way I was going to come out alive so I decided just to kill as many of the enemy as I could before they killed me. No, I wasn’t afraid: dead men know no fear.”

After the evening meal, the inevitable party started and went on for some time with the staff of the Centre and our porters at the centre of it--and VC Saheb showing himself to be a very accomplished mover!

On 22 July 2004, four years after his death, his Victoria Cross, WW2 campaign medals, and Indian medals were sold by Agansingh’s family at an auction in London for the sum of £115,000.

Agansingh slept in the Welfare Centre that evening and was there to bid us goodbye in the morning before we headed up the short but very sharp climb to Okhaldhunga. Little did we imagine that within a year we were destined to meet again and to spend even more time in his excellent company. It was a rare privilege and pleasure to meet and get to know these men of valour: Agansingh, Gaje, Ganju, Bhanbhagta, Lachhiman. All have now departed this world — but never to be forgotten!

::::::::

Sam Cowan Sam Cowan is a retired British general who knows Nepal well through his British Gurkha connections and extensive trekking in the country over many years.

Perspectives

9 min read

With rising temperatures all but certain, Nepal must focus on a more realistic and comprehensive emissions reduction strategy, strong regional cooperation, and effective global diplomacy.

COVID19

5 min read

The coronavirus pandemic highlights longstanding class differences and their unequal repercussions on our society

Features

8 min read

How Nepal’s imperial history resulted in today’s inequalities

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Writing journeys

12 min read

In this edition of Writing Journeys, Tom Robertson shares hisown insights on learning to write well, especially during thislockdown.

Features

7 min read

Siddhartha Aahuji would still be alive today if two hospitals had valued his life

Features

4 min read

Where the federal government has failed, local governments have stepped in

COVID19

Perspectives

6 min read

In South Asia, social distancing directs violence, exclusion and bigotry upon the already marginalised