The Wire

Features

16 MIN READ

11 have been sentenced to life in prison while the Tharu community in Tikapur continues to pay the price for the horrors of 2015

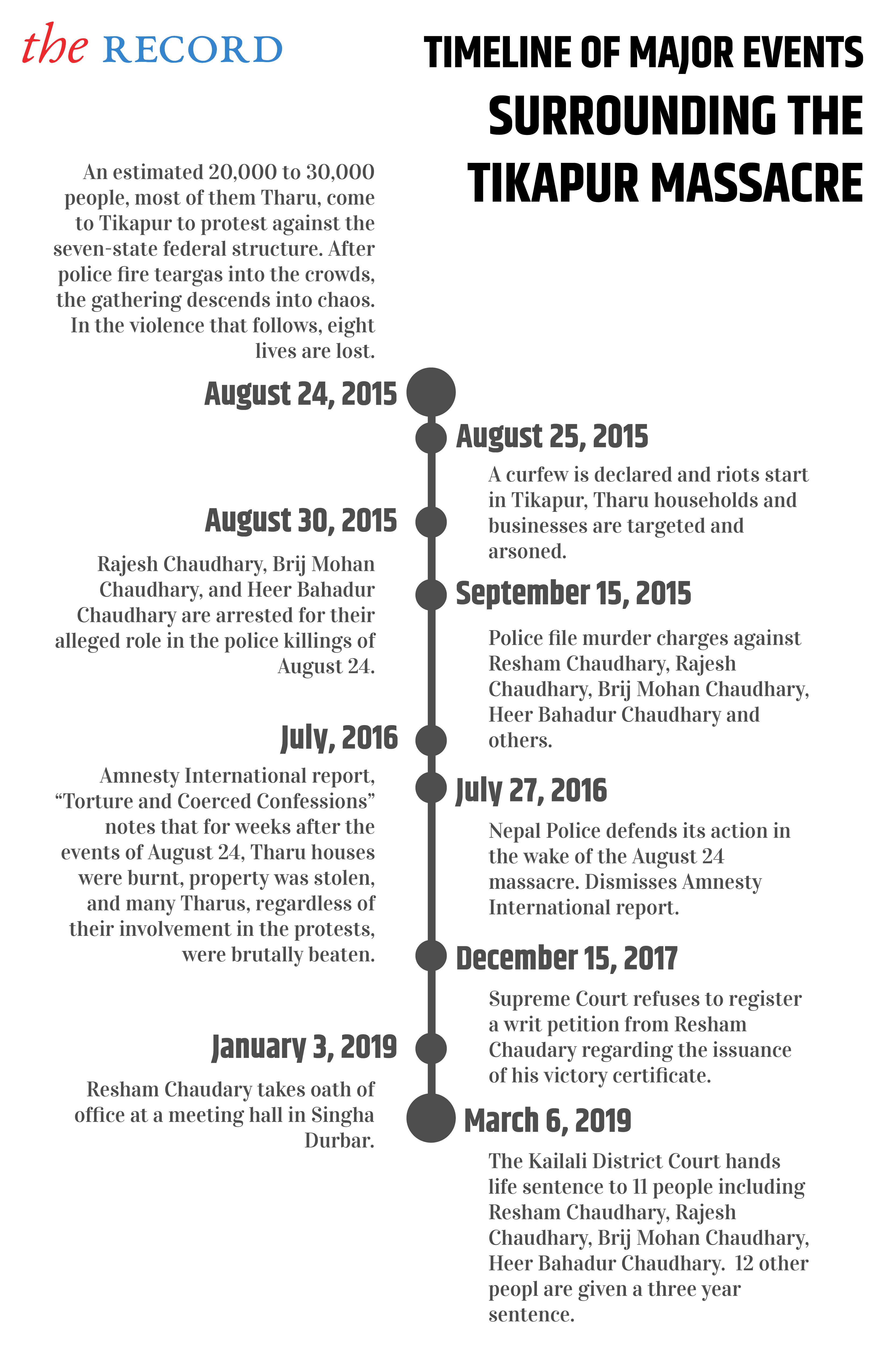

On March 6, 2019, Kailali District Court sentenced 11 to life imprisonment, pronouncing them guilty for their involvement in the Tikapur massacre of 2015 in which eight security personnel and a minor were killed. Twelve were sentenced with three years in jail, time that they have already served, and they will soon be free. Lawmaker Resham Chaudhary, who took his oath of office this January, is one of the 11 people slapped with a life sentence.

The verdict has come after three and a half years, but many, particularly those in the Tharu community, believe that the court orders issued by judge Parshuram Bhattarai are grossly unjust. They believe that the legal proceedings have been influenced by a hostile media trial.

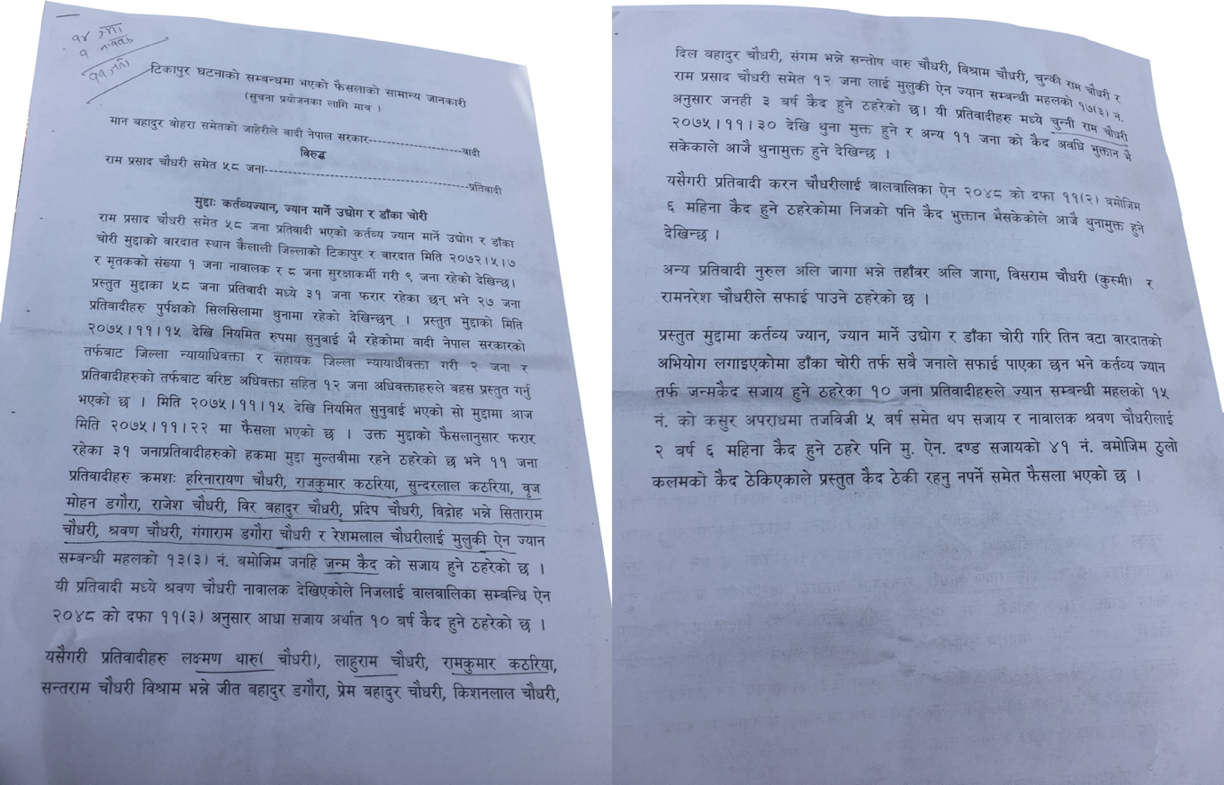

The Record obtained access to legal documents detailing the cases surrounding the police murders. According to a human rights lawyer who spoke on condition of anonymity immediately after the court proceedings, there was no prima facie case against many of those pronounced guilty. The documents show that the Nepal government filed a case against 20 people, including Resham Chaudhary, Rajesh Chaudhary, Brij Mohan Chaudhary, and Heer Bahadur Chaudhary for “murder, dacoity, and attempt to murder.” Evidence for these charges appears weak at best and fabricated at worst. Details of call records and witness statements in the documents do not contain conclusive evidence that any of these men were involved in murder.

Legal documents strongly suggest that the violence erupted spontaneously and the murders were not premeditated. The verdict is at variance with the assertion of many who have been claiming for three and a half years that the arrests were a retaliation against the Tharuhat political program.

A former senior judge told the Record that the verdict of the case appeared to be an attempt to dodge “trial by media.” Because the police deaths sparked such outrage among Tikapur residents, pronouncing anyone, particularly Resham Chaudhary, not guilty would make the judge in question unpopular. “The judge would be hounded with accusations by media that he was corrupt. In the current climate, it is easier for judges to pass the verdict that will be popular. Speaking for justice requires a lot of courage.”

That the verdict was passed without the report from government’s own inquiry being made public casts doubt on the verdict, according to Tikapur resident Shiv Narayan Chaudhary. To inquire into the truth about the killings and violent incidents that took place in the Tarai in 2015, including the Tikapur incident, the government set up a probe commision under the leadership of justice Girish Chandra Lal. According to Lal, who led the commission of inquiry, public interactions were conducted for victims to come forward, and the members of the commission visited each household that had registered a complaint.

“We spoke to the family of the 18-month-old boy who was killed, we collected photographs, and compiled everything in the report. We submitted the report to the government, and what is to be done with the report is the government’s prerogative, ” Lal said. The government’s decision to not make the results of its own investigation public, and the court’s decision to pass a verdict before ensuring that the findings of the government investigation are publicly available, indicate a lack of transparency and an intent to hide the truth.

Reema Chaudhary, Gokarni Chaudhary and Ramdaiya Chaudhary are three women whose husbands have been sentenced to life in prison. All three maintain that their spouses – Rajesh Chaudhary, Brij Mohan Chaudhary and Heer Bahadur Chaudhary – were not involved in the massacres, and have been sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes they did not commit.

Reema, 32, owns a small shop in Nawalpur village outside of Tikapur. In one corner of the shop she has a sewing machine; on the other, instant noodles, candy, and other small items that kids in the village might buy. There are a couple of rooms in the back of the shop where she lives with her 13-year-old son. This small house and her merchandise is all she has to her name. Policemen from Bhajani municipality raided Reema’s home in the middle of the night and took away her husband, Rajesh, without a warrant on August 30, 2015.

She remembers the night vividly. Her family was asleep when around midnight, men knocked on their door, saying, “Open the shop, we need to buy some things.” Confused and scared, Rajesh got up and, without opening the door, said, “The shop is closed right now.” The men started banging on the door and swearing, and eventually, Rajesh relented. There were policemen outside, and they dragged him out, beating him with sticks. They told Reema that her husband was being taken away for questioning about the August 24 incident in Tikapur and that he would be released soon. Three and a half years later, it turns out that Rajesh is likely to remain in prison for decades to come.

“My husband was illiterate, he wasn’t involved in politics,” Reema told the Record in late January. “We are poor. He brought vegetables from Tikuniya and sold them in the village, and worked as a manual laborer a couple of months a year.”

During a phone conversation after the verdict came out on March 6, Reema was crying, distraught. “Chhutenan,” (they didn’t let him out), she said. “I don’t know what to do, how to feed my son, send him to school, they won’t let him go.”

Gokarni, 42, said of her husband Brij Mohan, “They have tortured him so badly that it is difficult for him to sit, stand, do basic things. Even if they let him go, he’s not in any condition to work.” Gokarni claims that on the day the police killings took place, her husband was not in Tikapur but on his farm in Nawalpur, picking grass from the paddy field. Without her husband’s income, Gokarni is struggling to make ends meet, and her 16-year-old daughter’s exam results have been stalled because she has been unable to pay her school fees. “I farm on the little bit of land so that we have something to eat, I do manual labour to manage other costs, but it is not enough.”

Ramdaiya told the Record that her husband Heer Bahadur has been regularly beaten by the police in Dhangadi jail. “I don’t have money to send my three kids to school, I cannot support my family without my husband’s income. They let the others out, why not him?”

Tortured in custody

Both Nepali and foreign media outlets have extensively reported the events of August 24, 2015 in Tikapur. An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people, most of them Tharu, came to Tikapur to protest against the seven-state federal structure. They were demanding a separate autonomous Tharuhat province, in opposition to many in the Pahadi community who were for “Akhanda Sudurpaschim” (an undivided far-west). Some Tharus had household weapons with them, but the rally started peacefully. After police fired teargas into the crowds, the gathering descended into chaos. In the violence that followed, eight people lost their lives, including SSP Laxman Neupane, Police Inspectors Balaram Bista and Keshav Bohara, Constables Laxman Khadka and Lokendra Chand, APF Head Constables Ram Bihari Chaudhary and Lalit Saud. Saud’s 18-month-old son, Tek Bahadur, was also killed.

Rage on behalf of the slain police officers and their families permeated mainstream media reports about the incident, while journalists deemphasized, if not outright ignored, the destruction wrought upon the Tharu community in and outside of Tikapur in the aftermath of the police killings. The Human Rights Watch report titled “Like we are not Nepali” and the Amnesty International report, “Torture and Coerced Confessions” note that for weeks after the events of August 24, Tharu houses were burnt, property was stolen, and many Tharus, regardless of their involvement in the protests, were brutally beaten.

The “revenge” for the killing of the police officers, which many Tikapur residents took into their own hands, had an undeniably racial and ethnic dimension with the Tharu community at large being held responsible for the actions of the murderers.

“On the streets you would hear Pahadi boys yelling ‘Tharus need to be killed’,” said Aarti Chaudhary, an agriculture student and a resident of Tikapur. “A curfew had been imposed but it only applied to Tharus. Pahadis would walk around freely, but we [Tharus] could not step out without fearing for our lives.” Aarti believes that police officers not only did not prevent locals from beating Tharus and looting their property, but were actively involved in the violence. Security forces were part of the angry mobs that marched into people’s houses and ransacked their belongings, stealing items of value before setting everything on fire.

“I continued reporting but had to go into hiding because I didn’t know what would happen to me if I went outside,” said Ganesh Chaudhary, a journalist based in Tikapur. According to Aarti, policemen were interrogating local Tharus about Ganesh for weeks, intending to arrest him, or, she suspected, kill him.

Many say Tikapur Hospital was the first place where communal tensions came to a head in the aftermath of the police killings. According to the Human Rights Watch report, 35 police officers and 3 protesters were taken to Tikapur Hospital after the violence. The report quotes some family members of the slain officers allegedly saying to the police, “You are so impotent that you cannot even take action against those who killed your own. The Tharus did this and you just stood there watching.”

Krishna Gojihar is a health worker at Tikapur Hospital. On the day that the police officers were brought in, he was working in the emergency ward and saw the events unfold firsthand. “Naramro kisim ko mahol thiyo,” (it was a bad sort of environment), he said. “Some Tharu patients were attacked by people who came from outside, and the police, human rights people, nobody did anything. Some of us hid in the storeroom and in the toilet. We were only able to leave the hospital the next day, in an ambulance -- walking on the street was too dangerous.” Krishna still works at the hospital. He claims that while things appear stable and normal on the surface, “sadbhav” (goodwill) between the Pahadi and Tharu communities hasn’t been restored.

Presumption of guilt

Many Tharu residents of Tikapur recall how “protestors” at large were pronounced guilty even before the investigations began. Those who were at the scene, however, insist that a large percentage of the people who attended the protest did so thinking it would be peaceful and had no role in the police murders.

Some media outlets used the killing of an 18-month-old boy to highlight the inhumanity of the protestors, but Tharus in Tikapur claim that the little boy was accidentally shot by a policeman, not murdered by anyone in the Tharuhat movement.

“Tharus had bhalas and other household weapons. Even the police know that Tharus didn’t have guns. How, then, could a Tharu have shot a little boy?” said Aarti. The postmortem report for Tek Bahadur showed that he had been shot by a Lee Enfield (“.303”) rifle, a World War II weapon that does not shoot bullets straight but in a spiral. Many have inferred that the shot was fired by a policeman to disperse the crowd of protestors, and because bullets from the gun land unpredictably, Tek Bahadur was tragically killed. The Record contacted Tikapur police about their statement regarding the events, but the police refused to discuss the matter.

A 2016 report by the Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURINIP) states that the majority of those who are in jail due to their alleged involvement with the police murders have been tortured and ill-treated in police custody. The Amnesty International report concurs with this finding, stating that the detainees, who are in Dhangadi jail, “provided consistent accounts of beatings with lathis, being hit with rifle butts and being slapped and verbally abused.” The report states that a 14-year-old Tharu boy is among those tortured by security forces, and beaten into “revealing” the names of the policemen’s killers from August 24.

“The right to access to justice for these people has clearly been violated,” said human rights lawyer Shankar Limbu, one of the authors of the report. The report states that the arbitrary arrests of Tharus and violence by security forces and local Pahadis after the August 24 incidents violate the right to a free and dignified life, the right to assemble peacefully, the right against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, the right to free trial, child rights, the right to education, the right to health, cultural rights, and the right to property. Limbu, who is vocal about the rights of indigenous peoples in Nepal, believes that those in jail have been locked up under fabricated charges, for the sole reason that they are Tharu, and mainstream media has misrepresented the events (particularly the death of the 18-month-old child) to further a particular political agenda.

Loss of Confidence in the State

Even for Tharus who are not in jail, the scars of 2015 remain fresh. Shiv Narayan Chaudhary owns Niru Traders, a large supplier of electronics in the far-west. His store was one of the first Tharu properties to be arsoned on August 25 after a curfew was declared. Merchandise worth crores was destroyed, and Shiv Narayan lived in Singahi, India for months after the incident, fearing what would happen if he came back.

Shiv Narayan Chaudhary and Nirmala Chaudhary in their store that they recently rebuilt after it was arsoned in 2015. Photo Credit: Peter Gill

“Even now when I see these officers with their sticks, I get very, very angry,” said Shiv Narayan. “If those who are in charge of protecting you are the ones who set your homes on fire, what can you expect from this country?”

Shiv Narayan wanted to turn his burnt store into a museum to remember the violence that was inflicted upon Tharus after August 24.

"Leave the ashes, the damaged things, everything.”

It was in 2017, two years after the events, that he decided to begin rebuilding his home and his store again.

Shiv Narayan’s wife Nirmala Chaudhary, a schoolteacher at Jana Prakash Adarbhut, walked around the building pointing to all the changes in the store.

“There used to be grills here, these beams are new.”

Nirmala was teary eyed recounting the events. Her sister was due to deliver a child on August 25, and she was at home when the building was set on fire by Pahadi boys that she refers to as “Akhandes” (supporters of the “Akhanda Sudurpaschim” movement). She and her sister escaped through a window on the third floor of the building.

“Two Pahadi boys who saw us coming out helped us find a place to go,” she said. “They told me, ‘Aunty, don’t speak Tharu language, they will attack you, come with us.’”

When asked if he is still fearful of the people who destroyed his property, Shiv Narayan Chaudhary said, “I don’t have anything to fear anymore. What more can they do, kill me? If my whole community dies, what is the point of me living?”

Nirmala interjected, “My husband is not fearful but I am. I want to sell this store and move somewhere else, maybe in a village, where we can live peacefully.”

Shiv Narayan and Nirmala’s daughter Prerana graduated with a bachelor’s degree in architecture this year, and she was in Kathmandu when her house was set on fire.

“I was calling everyone in Tikapur to get hold of my parents but I wasn’t able to speak to them. I was terrified, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat. Eventually I spoke to my uncle who told me that they were okay, but I was in so much pain and fear,” she said.

Prerana believes that the relationship between Pahadis and Tharus in Tikapur has been irrevocably damaged post-2015.

“When Pahadi neighbours ask me ‘nanu, how are you?’ I grit my teeth. I will respond politely but I can’t forget that these are the people who looked on and did nothing when my mother and father were in so much difficulty,” she said.

Aarti Chaudhary also claims that the incidents are not simply a relic of the past.

“Tharus still live in fear. It is the Pahadis who have the most power and many are very racist towards us.”

While they are dissatisfied that no action has been taken against perpetrators of the violence, Shiv Narayan and Nirmala said that they are grateful that they eventually received compensation for their damaged property from the government. During Sher Bahadur Deuba’s prime ministership and Bimlendra Nidhi’s home ministership, Tharus who suffered financial damage got between 60-70% of their property’s worth two years after the incidents. This too was reported in a partisan manner by major media outlets. “Tikapur incident-accused get hefty compensation,” reads a Republica headline from June 2017.

What now?

The court verdict is a turning point for those who have been freed. But those who have been sentenced to life in prison remain in limbo, certain to continue legal battles into the high court, according to Gajendra KC, defense lawyer of the accused. Journalist Ganesh Chaudhary said that Tharus are dissatisfied with the verdict. “Nobody has been prosecuted for crimes committed during other political movements but Tharus have been targeted by a state that is prejudiced against them,” he quoted Resham Chaudhary’s father. Chaudhary said that security patrolling in Tikapur has increased considerably, and the Tharu community is aggrieved and confused. Their future political action will likely be shaped by their disappointment with the March 6 verdict.

Opinions

7 min read

Will your leadership summon the courage to end impunity?

Perspectives

7 min read

Dilly dallying with local elections over a discourse on legal conflict so close to the election date sets a terrible precedent for a young republic like Nepal.

Photo Essays

3 min read

A 70-year-old daily wage worker from Dolakha struggles to find work amidst the lockdown in India

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all the COVID19 related developments that matter

COVID19

News

5 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Explainers

3 min read

Information Minister Gokul Baskota resigned on Thursday after he was caught demanding bribe in a leaked audio. Here's what you need to know.

COVID19

News

4 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Features

6 min read

Khatiwada has mastered the art of remaining the go-to economist for Nepal’s communist leaders and of helping them cement their grip on power