Features

9 MIN READ

Over 100,000 Bhutanese refugees have been resettled in third countries but 7,000 remain in camps in Nepal, hoping that one day they will be allowed to return home.

Growing up in Bhutan, Gopal Gurung remembers his father, who was a government official, going to the royal palace clad in a daura suruwal. Up until the late 70s and early 80s, the Gurung family spoke in Nepali and wore ethnically Nepali clothes. But by the mid-to-late 80s, all of this had changed.

“Women were no longer allowed to have long hair and you had to wear gho and kira [traditional Bhutanese dress] to go to the market,” said Gurung. “Basic rights that you are entitled to in a democracy were taken away.”

Tensions had developed between the Ngalop Bhutanese majority and the minority Lhotshampas, ethnic Nepali migrants. Confronted with a growing Nepali population, the Bhutanese government embarked on a series of measures aimed at forcing them to assimilate into Bhutanese society. The driglam namzha, a traditional Bhutanese dress code and code of etiquette, was enforced for all citizens and Dzongkha was instituted as the sole national language. Ethnic Nepalis were forced to assimilate under pain of fines, imprisonment, or eviction from the country.

“We were classified as terrorists for talking about democracy,” said Gurung. “I was forced to hide in India while my father was imprisoned for six months. My wife, who had just given birth to our youngest daughter, was taken to the police station at 2 am for questioning. They wanted to imprison me and make us sign a migration form.”

Afraid that ripples from the Gorkhaland movement in the hills of India’s West Bengal and the 1990 people’s movement in Nepal would lead to similar demands in Bhutan, the Bhutanese government cracked down on what it called “illegal immigrants”. But many legal migrants, who had been living in Bhutan for generations, were classified as illegal as government officials refused to accept their legal paperwork. When the Bhutan People’s Party, which represented the Lhotshampas, organized demonstrations and protests, the Bhutanese authorities cracked down hard, leading to clashes and violence. Using these sporadic incidents of violence as a pretext, Bhutan began to expel Lhotshampas, according to numerous reports by human rights organizations. By the mid-1990s, over 100,000 ethnic Nepali Lhotshampas had been forcefully evicted, not just from their homes but from the country itself.

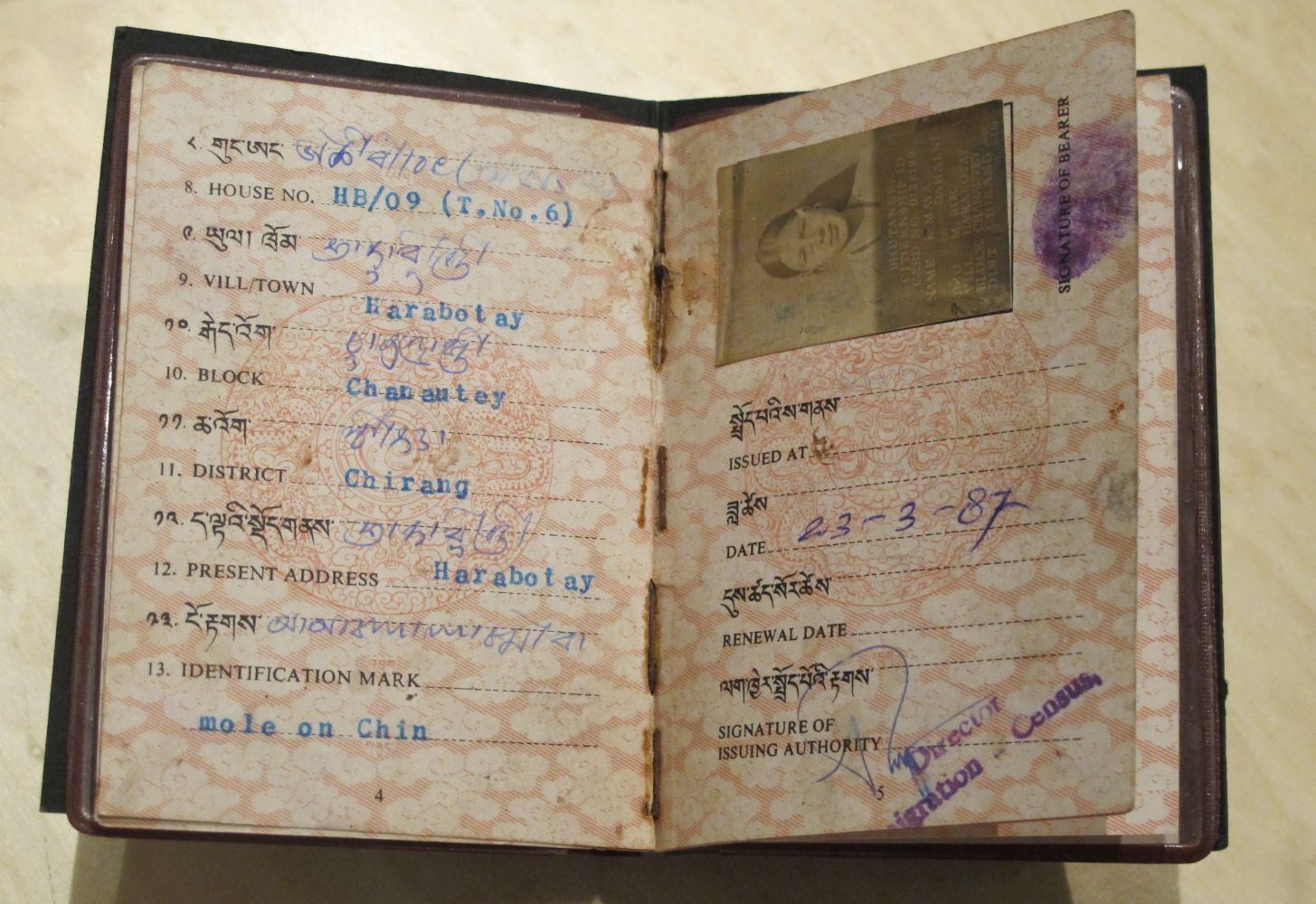

Among rights workers and organizations, the Nepali population, and the Nepali diaspora, Bhutan’s expulsion of its citizens is well-known. The history of forcible exile and the events leading up to it have been extensively documented by human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. But the international community at large has long appeared unaware – or unwilling to reckon with – of the plight of Lhotshampas. Bhutan’s international image continues to be one dominated by the romanticized ideal of a mystical Buddhist country that prioritized ‘happiness’ over material wealth. The country’s biggest soft power export has been its much-heralded ‘Gross National Happiness’ as opposed to Gross National Product (GNP) or Gross National Income (GNI).

The eventual forceful eviction of more than 120,000 of its citizens, which Human Rights Watch has called an ‘ethnic cleansing’, is often subsumed in the international media by orientalist notions of a spiritual, mystical, happy Bhutan. Those refugees all ended up in Nepal, despite the fact that Nepal does not share a border with Bhutan. India ignored the humanitarian crisis of the refugees and according to Amnesty International, even harassed the refugees and forced them to move on to Nepal.

“I will never forget a distinct sight when I was 19 years old. We were in India and our women and men had blood dripping from their bodies. Some were victims of rape, others had wounds all over their bodies. But there was no medicine. Children had diarrhea but no one would help. We were left to die so we came to Nepal,” said Ram Karki, a Bhutanese refugee and rights activist.

As refugees began to stream into Nepal, the country sought the help of UNHCR, which set up seven camps in eastern Nepal. The refugees would languish in those camps for over a decade.

“I spent 16-17 years in a refugee camp [in Nepal]. It was devastating having to leave Bhutan,” said Bharat Dahal, who was among those forced out in the 90s. “As a young individual, I was confused and frightened regarding what the future held for me. I was not alone in this dilemma. Nepali-speaking Bhutanese were all at crossroads.”

Dahal now lives in the United States as part of a resettlement program for Bhutanese refugees led by UNHCR. Gurung too has settled in The Netherlands with his family. After negotiations with Bhutan to readmit its exiled citizens went nowhere, international organizations like UNHCR and IOM stepped in to coordinate resettlement in third countries. As of January 2019, more than 110,000 Bhutanese refugees had been settled in countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

However, the wounds of the ethnic cleansing continue to fester. Suicide rates among the nearly 96,000 Bhutanese refugees resettled in the United States were reported to be twice that of the general population, attributed to culture shock experienced during resettlement, shifts in traditional family structures and dynamics, and the loss of culture, community, and wealth.

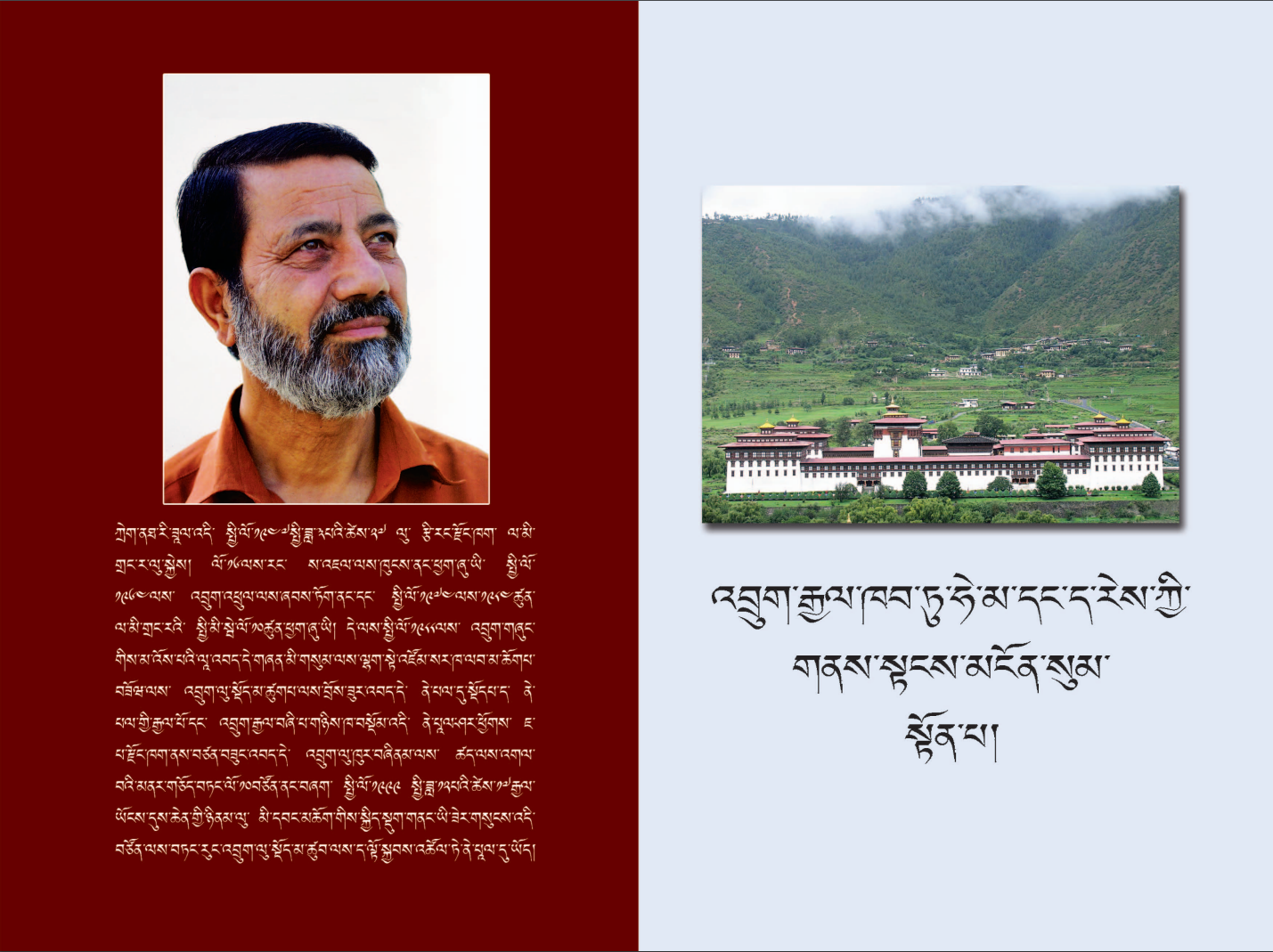

“Families have been permanently separated. No one talks about the increasing suicide rate of Bhutanese refugees in the USA,” said Teknath Rizal, a former Bhutanese political prisoner. Rizal was imprisoned for 10 years by the Bhutanese government, leading Amnesty International to dub him a ‘prisoner of conscience’.

Once a royal advisory councilor to the king of Bhutan, Rizal was imprisoned from 1989 to 1999 for speaking out against the treatment of Lhotshampas. While in prison, Rizal says he was subjected to mental and physical torture. In his memoir Torture Killing Me Softly, Rizal even claims that the Bhutanese authorities employed mind control techniques on him. Rizal’s voice broke as he recounted his experiences to The Record, a sign that he remains scarred by what he went through in those 10 years in custody.

“Bhutan is our homeland,” he said.

Since being released in 1999, Rizal has become an outspoken advocate for Lhotshampa rights and for holding the Bhutanese government accountable.

According to Rizal, Nepalis in Bhutan predate the ruling Wangchuck dynasty by 300 years. An article in The Diplomat traces the origin of Bhutanese Nepalis to 1620 when Newa craftsmen were commissioned to build stupas in Bhutan. Gurung even traces Lhotshampa origins to the reign of Ram Shah in Gorkha, when Nepal was still divided into 22-24 principalities.

“Bhutanese of Nepali origin didn’t just occupy land in Bhutan. We paid taxes to the government and settled down,” said Gurung. “We had to pay 1 rupee tax per house but the amount differed if you wanted to raise cattle or keep bees.”

It is because of these age-old ties to the land and country that many Bhutanese refugees have refused third-country resettlement in the hopes that one day, they will be allowed to return home.

“Let us not forget that we still have around 7,000 refugees in refugee camps and approximately 80,000 of our relatives in Bhutan still lack citizenship due to our involvement in the 1990s movement,” said Karki, who has resettled in The Netherlands.

According to Vipasana Karmacharya, a former community service officer at the Bhutanese Refugee Project, out of these 7,000 Bhutanese who remain in camps, those who were born in Bhutan and grew up in Bhutan want to end their lives in Bhutan.

“Our children are in the US, but we did not want to go and adapt to a completely new culture again, we want to see our motherland one last time before we die,” Dambar Kumari Khatiwada told Nepali Times in 2021.

But even if they are accepted back by Bhutan, there is no guarantee that they will be allowed to live peaceful lives. More than two dozen Lhotshampas remain political prisoners in Bhutan’s jails, as documented by Devendra Bhattarai for the Center for Investigative Journalism Nepal.

“There is no happiness for Lhotshampa in Bhutan. There is no freedom of expression, no democracy in Bhutan,” said Rizal. “It's all a play.”

The young Bhutanese King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck has attempted to democratize the country but Bhutan still remains a stifling monarchy where lese majeste laws are still in effect. Any criticism or disrespect of the royal family can lead to prison. And any talk of the expulsion of Lhotshampas remains taboo. Even young, progressive Bhutanese refuse to publicly comment on the Lhotshampas for fear of persecution by the government, as was evident when The Record attempted to speak to some Bhutanese.

“Bhutan’s prison system and criminal justice are cruel, barbaric, and inhuman,” writes Rizal in his book.

Despite the conditions that might await them in Bhutan, many of those who remain in refugee camps want to return to their home country. Most of them are old and their children have resettled around the world. They have little left except for a sense of belonging. Bhutanese rights activists stress that Bhutan must accept its citizens back and publicly acknowledge the eviction of Lhotshampas through reparations.

And in spite of all the hurt that the country has caused them, those who have settled elsewhere still retain their love for Bhutan and understand why some might still want to return.

Says Dahal: “You can never deny the love for your mother.”

Features

3 min read

The authorities are finally being forced to address corona-related issues in prisons, but they still remain far too crowded

Features

4 min read

Where the federal government has failed, local governments have stepped in

Features

9 min read

The formation of a Cyber Sena to defend Prime Minister Oli’s interests raises the spectre of censorship, trolling, and harassment.

COVID19

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Features

5 min read

The mass-quarantine centres in Nepal are only adding to the suffering of migrant workers returning from India

Features

5 min read

Ranjan Koirala’s release from custody represents just the latest failure in a series of cases bungled by Nepal’s supreme court

COVID19

News

3 min read

Preventing coronavirus spread in Nepal’s overcrowded jails is becoming near impossible

COVID19

News

5 min read

The Valley’s CDOs got the government’s green light to clamp strict measures on account of rising case numbers