Features

8 MIN READ

Analog photography is a relic from a bygone era, yet a few enthusiasts still continue to keep the spirit of film alive. But for how long?

Nineteen-year-old Sukarya Lal Shrestha has been taking photographs for quite some time. He frequents old Kathmandu streets with his trusty digital SLR camera looking around for capture-worthy shots. However, recently Shrestha has also started to carry with him a film camera alongside his other camera equipment.

Shrestha, who only recently got his second roll of 35mm film developed, shared that he first got curious about film photography when he came across videos about the process on YouTube. “I used to watch channels like Grainydays and Badflashes that mostly have content on film,” shared Shrestha. Having followed the process extensively online, he mentions that he also started socializing with others who had also dabbled with film photography.

But why would one revert back to using clunky hard-to-use analog cameras when their digital counterparts have grown to become so much more efficient? Even smartphone cameras that nearly everyone seems to carry in their pockets arguably take much better photographs than most analog cameras ever could. The reason here seems to have to do more with process rather than with result.

Jagadish Upadhya, the man behind Film Foundry in Jawalakhel, shares this notion. Upadhya, who is now in his 60s, shared that he has been smitten with photography for as long as he can remember. When asked about how he was first introduced to photography, Upadhya said, “I can’t remember how or when. It’s been so long.”

What is even more interesting about Upadhya as a photographer is the fact that he has made the choice to shoot exclusively in film. “Back when I started, film was the status quo. When the switch started happening, I was not interested in digital cameras at all. I decided that I’ll practice what I know, so I stuck with analog, and I’ve been with it ever since,” said Upadhya. Film purists like Upadhya are adamant that film photography has a certain je ne sais quoi to it, as opposed to its digital counterparts.

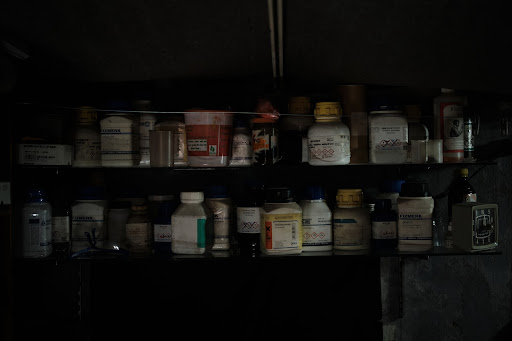

Upadhya even goes the extra mile and develops, scans, and prints all of his photographs with his own chemistry and in his own studio. If you ever go through Upadhya’s studio at Film Foundry, you will see an array of chemical bottles on wooden shelving, prints hanging near the low ceiling, and rolls after rolls of negatives waiting to be scanned. Even back when darkrooms were still fairly common, Upadhya would still prepare all his photographs on his own. He said, “I’ve been having my own darkroom for the past twenty-five years.”

This again brings up the question, why would one take all the hassle with film when its digital alternative is so much more easier? For Upadhya, he says that it is because he is in love with the entire process that it takes to see his photographs. He excitedly showed me a pinhole camera he had engineered a few days prior, alongside a medium format negative of an image he had just a few hours ahead. “When you do these things yourself, it’s fun. The process makes my photographs a lot more personal. I’m always excited to find out how the photograph I took turns out to be,” he said.

However, while it might be that the process of film photography captivates people, actually managing to put up with the little details of it is something that is easier said than done. Veteran photojournalist Bikas Rauniyar is one of many individuals who has had to extensively work with film photography.

Rauniyar, 54, may have hung his old analogs a long time back, but when he started his career, film was all that was used. In fact, film photography is so much ingrained in Rauniyar’s muscle memory that he admits that he is still pretty stingy with the number of shots that he takes with his modern-day cameras. “Oftentimes my mind still thinks that I have a limited number of shots like I had in analog cameras,” shared Rauniyar.

“With film, you’d only get 36 images per roll. So the challenge was that you could not take as many images as you wish during an event. Moreover, you wouldn’t even know if the images that you took looked alright,” explained Rauniyar. He goes on to say that his editors then had set the cardinal rule that out of every three shots taken, at least one needed to be usable.

But getting the right shot was only the first part of the job, said Rauniyar. Unlike today, when one can simply email images from one location to the other, back then photographers like him did not have such luxury. Even viewing your photo on paper involved a tedious process that required working in pitch-black darkness while dealing with delicate chemistry.

Photojournalists such as Rauniyar had the added pressure of having to meet strict deadlines. Rauniyar shared that publications such as Kantipur had their own in-house darkrooms; however, these darkrooms were only equipped to process monochrome pictures. This meant that when the paper did finally decide to start printing colored papers, photographers would have to run across town to the few photo studios that could quickly and correctly develop colored film.

“Typically for colored rolls, they would be taken all the way to Hong Kong just to be developed which meant it would take too long for the daily paper. Eventually, some photo studios like Photo Concern and Hikola started to develop color photos as well. During this time, it was usual for us to go back and forth from the field to the newsroom and the color labs in our trusty motorbikes,” he recounted.

While working with film was certainly a finicky process then, it has gotten even harder today. Young hobbyists like Shrestha who want to continue film photography do not have a lot of options when it comes to the equipment they can get their hands on, the film rolls that they can buy, and even the places where they can get their photographs developed. Even big-name legacy photo studios like Photo Concern no longer sell or develop film.

“We stopped developing film reels three-four years ago, but if you have developed negatives we can scan them for you,” was the answer given by one store clerk at Photo Concern.

And while you can find used analog cameras and lenses in a handful of camera shops, most of the time, these pieces of equipment have been ill-kept and jacked up in price. Moreover, finding the exact gear that you are looking for is a rare occurrence, and you end up having to settle for something that you did not really have your eyes set on.

Amateur enthusiasts like Shrestha have had to make do with what they can find and afford. “I’d say the hardest part of film photography is the financial aspect of it. Film rolls and development fees aren’t cheap,” said Shrestha who tries to keep costs down in multiple ways, including scanning his own negatives after they get developed at the Analog Club Nepal.

“I shot my first roll of film on a camera that I had borrowed from a dai,” he shared.

In truth, enthusiast-run spots like Film Foundry in Jawalakhel and the Analog Club Nepal in Maruhiti are perhaps the last few places in the valley where you can still get your film developed. Upadhya even showed a roll of 35mm film that he was sent all the way from Dang.

Sanjog Manandhar, 37, is a photojournalist and one of the brains behind the Analog Club Nepal. Through the club, Manandhar has managed to create a sort of hub where enthusiasts can get film, as well as develop, scan, and print their photographs. Outside the club, there is even a wooden bulletin board that lists a bunch of different film rolls with prices that range from as low as Rs 500 for film that expired in 2012 to Rs 1,700 per roll. The menu also tells that the club charges Rs. 800 to develop color negatives and Rs 500 to develop black-and-white negatives and the same to scan them.

Unfortunately, while the menu outside of the club does list a good selection of films, Manandhar shared that more often than not the club will only have a limited supply of a specific film with no certainty as to if or when they will get another batch.

“Right now we only have the Fujicolor C200 on hand. That too in very limited numbers,” shared Manandhar.

According to him, even buying film and development chemicals is a daunting task. “We have to constantly rely on contacts living or traveling abroad to help us get the rolls or equipment we want. And because of that, we can’t even get them in large quantities,” said Manandhar.

Even when Manadhar was first setting up his darkroom in 2018, he had to go about old camera shops and studios hoping to salvage developing and scanning equipment that might have been sitting around and gathering dust. Upadhya, who also often has to call in favors to find the films he wants, shared that film photographers in Nepal need to make do with what they have. “Beggars can’t be choosers,” he said.

Nevertheless, despite all the difficulties that film photography seems to carry, both Upadhya and Manadhar share that as of late, a lot more faces have been showing up to their darkrooms to get their pictures developed. “I see a lot of teens and young adults dropping by the club to learn and try out film photography after they’ve seen it on social media,” Manandhar happily shared. He continued, “Older photographers too have again begun to rediscover film photography as well.”

Even Rauniyar shared that he has recently been going about making digital scans of all his old negatives lying in his archives.

“Maybe if enough people start doing it, it’ll be an easier thing to do,” hoped Manandhar. Upadhya however, is not that optimistic. “Is film making a comeback or is it just a passing fad, I cannot say for sure. Many people tend to try it once but then don’t come back because film is inconvenient,” he complained.

Regardless, both Manandhar and Upadhya believe that there is still a place for film photography in a time that is overrun with digital cameras. Upadhya believes, “I know that analog photography will always be there, but I think it’ll stay as an art form.”

Sajeet M. Rajbhandari Sajeet is a Media Studies undergraduate and is currently reporting for The Record.

Features

7 min read

Amid a proliferation of cheap, fast fashion clothing, young Nepalis are turning to conscious clothing and shopping for second-hand apparel.

Features

6 min read

Meet six young Nepali artists with stories to tell, styles of their own, and a passion for art that’s digital.

Features

12 min read

Kesang Tseten, in documenting these grueling stories, has done his part by successfully bringing the experience of the Nepali migrant worker to our attention, and has thus recorded history in unforgettable images.

Features

8 min read

Rajbhandari’s artworks reflect not only her evolution and range as an artist but also her ability to combine emotions with core art forms.

Features

Longreads

Popular

Recommended

22 min read

They stole our ghats. They stole our boats. They stole our rivers and our fish. Crushers in our rivers, they even stole the lands of our ancestors.

Features

Photo Essays

5 min read

In his two decades of work, Subha Ratna Bajracharya has chiseled many iconic structures, many of which can be found in temples and landmarks all across Nepal and around the globe.

Features

11 min read

The Kathmandu Triennale 2077 attempts to delineate the concept of time, explore the fluidity of identity, and celebrates art in all its forms.