Features

13 MIN READ

A collective effort by activists, historians, journalists, and curators has resulted in the return of stolen Nepali artifacts from foreign lands, but constant vigilance is still necessary.

Stolen, lost, returned, found, vandalized, destroyed in natural disasters, memorialized for their beauty in other artworks, such are the travails and adventures faced by the living heritage of Nepal, priceless artifacts that are still worshiped, endangered by their very beauty and the profound history and meaning that resides within and without.

Since Nepal opened up in the late 1950s, Kathmandu’s particular charms drew people to it — for marijuana, for spiritual awakening, often both, one supposedly following the other. Irresistible to a generation who were reeling from post-war malaise, the idea of a Shangri-La-like haven drew thousands of hippies who became entranced by a skyline and landscape saturated with temples and idols, all against the backdrop of the Himalaya.

With the influx of outsiders came the interest of anthropologists, art historians, and a recognition of long-undiscovered treasures densely spread throughout the valley and larger Nepal, mainly from the Newar era that spanned centuries. Over the decades, and concentrated in the 1980s, uncountable idols and temple pieces disappeared, stolen for collections and museums that tuned into their value, often with experts in the field whispering in their ears, urging acquisitions that never bothered with provenance.

Lost and found

These cumulative losses have now activated a usually apathetic civil society and today, a number of voices are being raised to address repatriation, often with heartening results. The most recent return of the long-lost Lakshmi Narayan idol to its shrine in the heart of Patan Durbar Square, and The Rubin Museum’s return of two exquisitely detailed wood carvings — a 17th century torana (a structure that typically adorns the top of a temple entrance) from the Yampi Mahavira temple complex in Patan and a 14th century part of an apsara bearing a garland from an ornamental window in the Itum Baha Monastery in Kathmandu — have brought heightened attention to a cause that had been taken up decades ago by the artist and art historian Lain Singh Bangdel and German collector-turned-activist Jürgen Schick.

With the frequency of findings and successful returns, arguments have been resuscitated regarding how to repatriate these pieces, even within Nepal itself. Should they be replaced in situ, would they be safe there, these are concerns that vary with each particular piece. Unfortunately, the safety of the pieces upon return seems to be a convenient argument against return, made mainly by Western collectors and museums that used this very caveat to rob the country in the first place. The point seems moot, the law never asks if stolen property should be returned to their rightful owners based on what might happen to the looted goods after.

Certainly, concern over the conservation of pieces in situ is not unfounded, even while it shouldn’t be used as an argument against repatriation. In the early 1990s, Erich Theophile and Rohit Ranjitkar of the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) rescued an entire window section, similar in style to the recently returned 14th century carving from Itum Baha. This one, featuring a vidyadhara, or bearer of wisdom, at its base was located in the Sulima Square in Patan and was part of a historic house. The old window had been discarded in favor of a new one by the owner. The window section had been sent to a junkyard. Theophile and Ranjitkar rushed to the yard to locate the window the very next day, finding all pieces intact. They bought it from the junkyard for the sum of Rs 2,500 and the piece was re-assembled and placed in the Trust’s office for many years for safe-keeping.

Today this 10th-11th century carbon-dated piece, the oldest recorded in the Kathmandu Valley, is in the Mul Chowk Architecture Gallery set up by the KVPT, adjacent to the Patan Museum. The piece could not be returned to a building which itself is no more. It was formerly the home of the Gayabajya, a famed Tantric Brahmin priest, and was torn down in 1997.

Such situations, common in the 80s and 90s, are now much rarer. Window sections like this would now sell for hundreds of thousands of Nepali rupees, most often to Nepalis themselves. Their value as free-standing artworks endures, retaining their beauty even after having been torn from the fabric of their buildings. However, many a piece has already been lost to the division of ancestral property and the tearing down of older structures to be replaced by new ones, with centuries-old pieces ending up on scrap heaps and bonfires before enlightenment dawned. The window fragment in the Architecture Gallery has been parsed piece by piece and explained with attention to its iconographic symbolism, the educative value making up, in some small measure, for its displacement from its historic place on the Sulima Square building’s façade.

Lakshmi Narayan’s return

The recently returned Lakshmi Narayan was stolen one night in 1984, from Patko Tol, in Patan, just south of the main Durbar Square. It was replaced by a smaller stone replica in 1993; that stone image now remains in the temple next to the returned idol. The story of its return seems almost fictional, spanning decades, and encompassing a wide cast of characters, each essential to its serendipitous return.

The narrative begins with the documentation of the idol by Krishna Deva, an Indian archaeologist, and Nepal’s own Department of Archaeology in a publication titled Images of Nepal, published in 1984. The idol disappeared later that year, perhaps even brought to attention by the very act of documenting it. (This has been pointed out in the FBI report compiled by Joy Lynn Davis, as part of the paper-work filed for the Lakshmi Narayan return). Lain Singh Bangdel then published that photo of the idol in Stolen Images of Nepal (1989), formally recording its theft. In 1990, a year after Bangdel’s book was published, the sculpture appeared in a Sotheby’s auction and was sold, buyer undisclosed, despite the claim of theft.

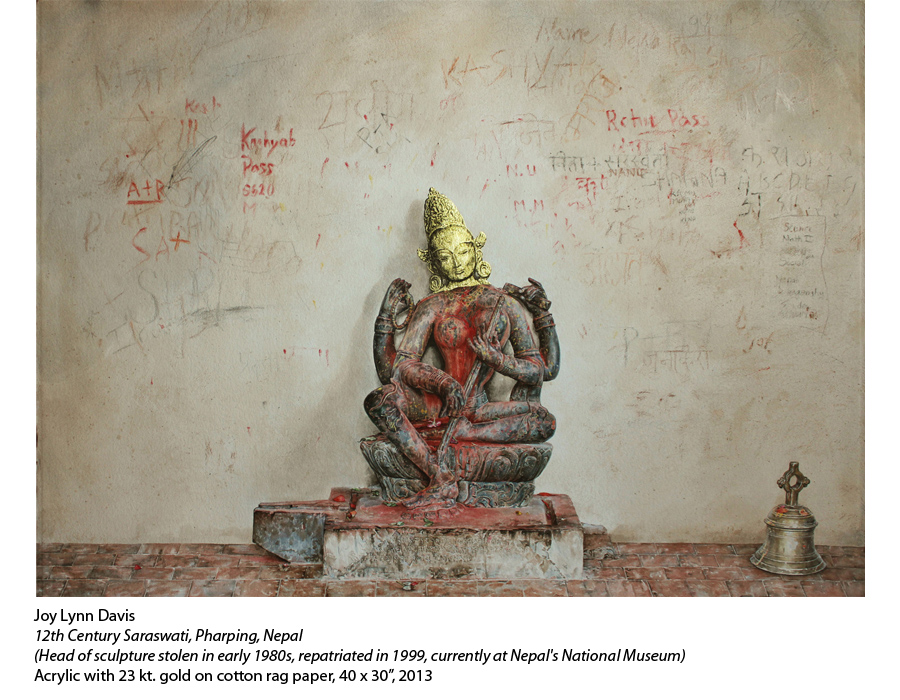

Enter artist Joy Lynn Davis, over two-and-a-half decades after the idol went missing. Starting in 2010, she had been coming and going from Nepal, visiting the site of 120 thefts and researching stories around the losses. This led her to conceive of a series of detailed landscape-like watercolors that would document some of the most prominent stolen images of Nepal, replacing the missing idol or piece with a gold-leaf rendition to highlight the loss. Her project eventually resulted in an artist’s residency with the Kathmandu Contemporary Arts Center (KCAC) in 2012. Living with a Newar family in Patan, she worked on 15 pieces for over five years. Each painting was heavily research-based, and one of them is of the missing Lakshmi Narayan idol. As she researched the missing pieces, and worked on the series itself, she got into the habit of scouring museum collections online and in books every few months to see what would pop up, trying to scan the globe for any and every sign of these missing artifacts.

In 2015, towards the end of her time in Nepal and just before the earthquake (she left after her show of works at the Nepal Art Council was cut short by the quake itself), one of those Google searches turned up the Lakshmi Narayan idol, exhibited in the Dallas Museum of Art, the very same city where her family is from. It was gifted to the museum by the collector David T. Owsley (it seems pretty much right after he bought it from Sotheby’s in 1990), and remained on display till 2020. The idol came up in the search only because a blogger had, by chance, taken some photos of the gallery it was in.

The Lakshmi Narayan was finally removed and prepared for return earlier this year — almost 37 odd years after it was taken.

But, back to Joy’s discovery in 2015. After her discovery, some of the players of what is now called the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) came in and began the complex work of filing reports to the Department of Archaeology, which then reached out to the governments in question, jumpstarting a byzantine process that included filing an FBI report. First with the earthquake, and then with the pandemic slowing things down, the idol was finally returned to Nepal in 2021 and reinstalled with pomp and ceremony in December of last year.

A community effort

The NHRC or an entity like it was first mentioned by Kanak Mani Dixit in his 1999 article, ‘Gods in Exile’ in Himal Southasian . It took almost two decades for this entity to actually manifest, chaired by former Director-General of the Department of Archaeology, Riddhi Baba Pradhan, and helmed by young journalist Alisha Sijapati, who is now the campaign director of the entity; Taragaon Museum curator and activist Roshan Mishra; Dixit himself; the aforementioned Rohit Ranjitkar from KVPT; Dilendra Shrestha, tourism advisor to Lalitpur Metropolitan City; Sanjay Adhikari, a lawyer who files all the complicated paperwork for repatriations such as that for the Lakshmi Narayan; and people like Lynn Davis who serve as advisors. Dixit had been searching for a group of people to take up the cause for years, but the untimely deaths of key art historians Dina Bangdel and Sukra Sagar Shrestha, followed by the pandemic had put a pause on the impetus until, almost magically, this particular iteration of people fell into place to form a highly effective and motivated group.

The NHRC is supported by Lost Arts of Nepal, essentially a Facebook group that cycles through thousands of images of lost artifacts and matches them, with in-depth research, to those pieces in collections abroad. The person behind Lost Arts of Nepal wishes to remain anonymous and their identity is known only to a few people (this writer not included) who guard it with zeal, respecting the privacy of an extraordinary individual who has single-handedly contributed so significantly to identifying multiple artifacts that have since been returned due to this key first step of matching missing work to collection.

As Nepal readies to receive such pieces, the Chhauni Museum, the repository where the pieces often transit before being returned to their place in situ, has put up an exhibition of the items in its keeping. The show opened at the end of March, featuring these remarkable pieces, before some, like the wood carving from Yampi Mahavira, are returned to their original location. There is now also an informal, verbal agreement with the Itum Baha caretakers, who have agreed to replace their copy with the original apsara piece.

As citizen activism has ramped up, so too have questions of the inner workings of art theft, as it was during the 80s when most objects were stolen, and today, as the world wakes up to repatriation, from the Benin Bronzes to Nazi loot that was ‘legitimized’ by museums. Dr. Emiline Smith, lecturer at the University of Glasgow, and Dr. Erin Thompson, associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, both experts on art crimes, were at the return of the Lakshmi Narayan ceremony in Patan this past December. It was most likely Thompson’s article for Hyperallergic, an online art magazine, in January 2020, that broke the news of the Dallas Lakshmi Narayan’s connection to the stolen idol of Patko Tol and prompted the museum to take the idol off display.

Emiline Smith outlines how the supply is indeed very much driven by demand, with Nepal being a hub or center of such activities due to its own density of treasures as well as a natural pied-à-terre between Tibet and India, becoming therefore, an unwitting hotspot for trafficked artifacts as they are funneled to the West. Her joint journal piece ‘The cultural capitalists: Notes on the ongoing reconfiguration of the ongoing trafficking culture in Asia’ explains how that historic demand now comes from within larger Asia, concentrated in China, Hong Kong, and Japan as economic power shifts and people with money seek to consolidate their cultural capital by buying Buddhist and Hindu antiquities to raise their status from parvenu to sophisticated art collector – the religious aspect being an added draw. Therefore, demand still remains, dialed down somewhat but very much present.

Constant vigilance

Even as we celebrate the return of pieces with the show at the National Museum, vigilance is essential. Nepalis can still be tempted to steal from their own, driven by economic need to loot something priceless for a sum that is a fraction of what it will eventually be sold for. And while we have awoken, for the most part, to the importance of the living heritage that resides with the idols and monuments, there are still horrific instances that shake even the most hardened, such as the breaking of the superb Chyasing Dega tablet in the dead of the night a few months ago.

The sandstone tablet, weighing 231.5 kgs, was found smashed to pieces one morning. Historically vital, a record from the era of Pratap Malla, located within the airy outer sanctum of the octagonal stone Krishna Temple in Kathmandu Durbar Square, it dates to 1649 CE and is inscribed in Sanskrit and Nepal Bhasa. The tablet was so remarkable, it had been documented in an artwork, just prior to its breaking, by skilled printmaker Kabi Raj Lama, who, by a stroke of luck, had documented this piece before etching the print for it, thereby immortalizing it in its whole form.

Lynn Davis’s first reaction to the breaking of the tablet was that perhaps it was too heavy to steal, and, like the magnificent Saraswati idol in Pharping where the statue was knocked over due its size and weight, the foot broken, and the head stolen, the motive here was to break up the tablet into pieces, making it easier to transport, and easier to hide. In an aside, it is important to note that female figures disappeared first, as observed by Jürgen Schick, their forms more palatable to the Western collectors’ notions of classical beauty. It only takes one look at Lynn Davis’s watercolor of the Pharping Saraswati to understand what might draw the eye of a covetous collector.

Going back to the Chyasing Dega tablet, Kathmandu Metropolitan Police reports, however, indicate a troubled woman and a dispute of sorts, as per their CCTV cameras, the temple being in very close quarter to the Hanuman Dhoka Police Station. It is perhaps hard to imagine how a mentally ill woman might have pushed over a 200-kilogram stone tablet (its fall from the ledge of the temple causing the fracturing), but Sandeep Khanal from the Department of Archaeology and Executive Director of the Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Museum, believes that the motive was not primarily theft but rather a deranged domestic dispute. The pieces have been gathered by the museum and are kept safely in the sanctum sanctorum of the Krishna Temple, no longer accessible to the passing public like before.

As Nepal prepares for further civil activism regarding our stolen heritage, it is important that we remain vigilant of that which we still have, in situ, but also on view in museum spaces, keeping the conversation current, buttressing the achievements of those mentioned here (but also many more who have not been named) who have worked so hard to bring back that which was thought irrevocably lost. The infinite, almost universal, value of these artifacts is emphasized further by the artworks inspired by them, the series by Joy Lynn Davis and the print by Kabi Raj Lama (he has made several substantial artworks of toranas and idols, often in situ, or surrounded by symbolism that contextualize their gravitas) are just a few examples of the reincarnations of these images.

Any loss of artifacts is heart-wrenching, the loss of idols that are rudely snatched while they are still worshiped makes Nepal different, it impacts our very social fabric, affecting places of veneration and how we look at the empty spaces, which eventually fall into ruin out of neglect.

Sophia L. Pandé Sophia L. Pandé is an art historian and filmmaker by training. She has been a long running columnist for the Nepali Times and The Kathmandu Post.

Features

6 min read

A retrospective of Lain Singh Bangdel's artwork in Queens revisits the life and times of the iconic Nepali artist, writer, and scholar.

Features

5 min read

Take a break from the gloom and doom of the pandemic and give Gauley Bhai’s infectious, energetic debut album a listen.

Features

7 min read

Amid a proliferation of cheap, fast fashion clothing, young Nepalis are turning to conscious clothing and shopping for second-hand apparel.

Explainers

13 min read

Some call NFTs a new era of ownership on the internet while others say it’s a fad and a threat to the environment. But what exactly are NFTs?

Writing journeys

13 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, US-based journalist and writer Sanjay Upadhya recounts his time working at The Rising Nepal under the Panchayat and the lessons he’s learned along the way.

Culture

5 min read

The second in the AxV exhibition series hosted by Kaalo 101

Features

12 min read

Kesang Tseten, in documenting these grueling stories, has done his part by successfully bringing the experience of the Nepali migrant worker to our attention, and has thus recorded history in unforgettable images.

Features

Longreads

Popular

Recommended

22 min read

They stole our ghats. They stole our boats. They stole our rivers and our fish. Crushers in our rivers, they even stole the lands of our ancestors.