Perspectives

Film

8 MIN READ

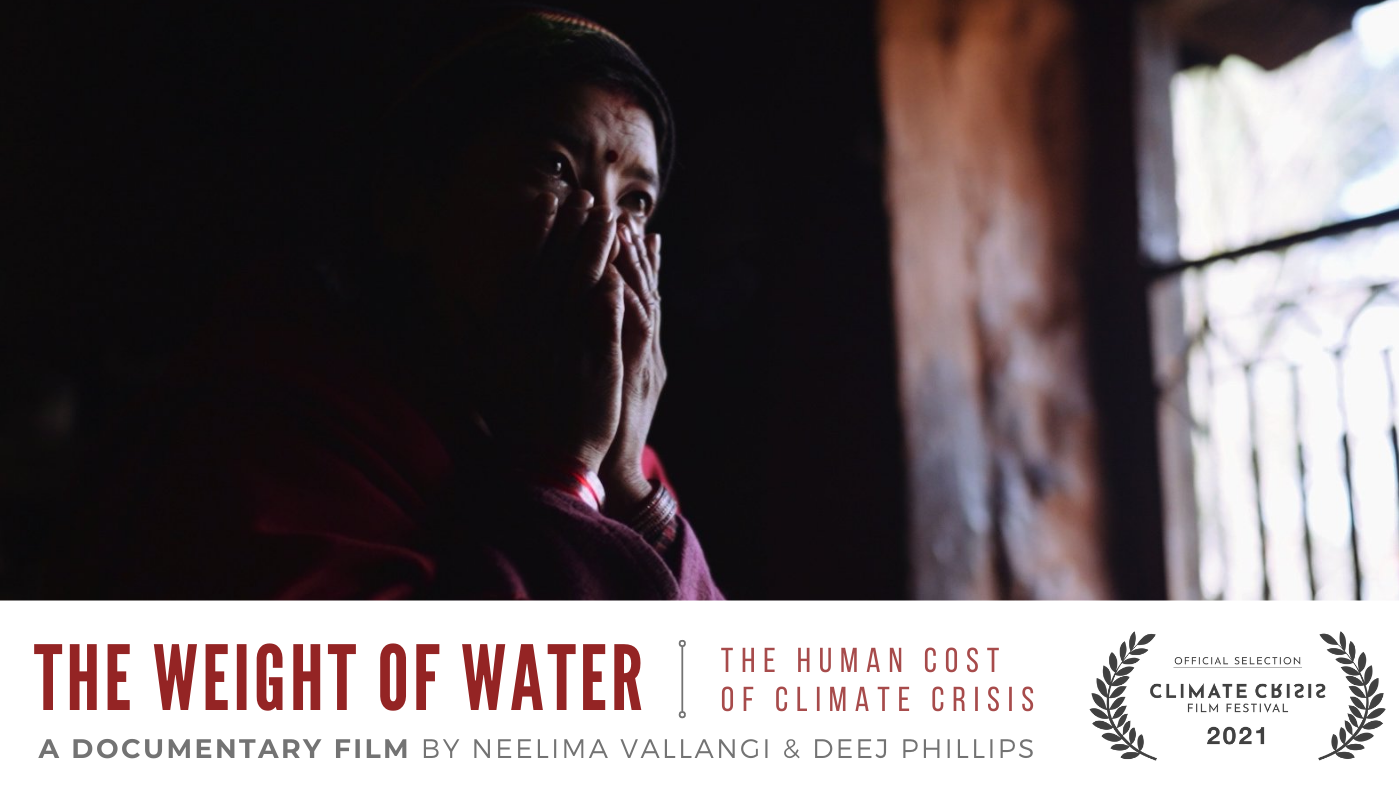

This feature documentary highlights the direct and indirect costs of climate change through three unique stories across Nepal, linked by its central theme: water.

The Weight of Water opens with a picturesque shot of a dense, amorphous hill surrounded by thick layers of fog sprawling across the frame. The head of a hilltop stupa peeks out as the aerial camera pans outwards to reveal a vast, misty horizon. The visuals are complemented by the sound of chirping birds.

Such a cinematic treatment of Nepal’s hills and mountains generally present the country as a remote, idyllic Shangri-La, tucked away from the worries of modern life. Tourism promotion ads, travel vlogs, and social media are full of this imaginary Nepal. This film, however, makes no such effort. Within a few seconds of the opening, the visuals are juxtaposed with on-screen text highlighting the reality of life in the hills of the Hindu Kush: “Nepal is home to 29 million people. They are responsible for less than 0.01% of global greenhouse gas emissions… [But they are] bearing the brunt of climate change.”

The Weight of Water is co-directed and co-produced by Deej Phillips and Neelima Vallangi. The feature-length documentary explores the complex, multifaceted, often unintuitive nature of climate change effects as they manifest in geographically diverse and economically developing countries like Nepal. It achieves this by focusing on three unique stories, each of which is linked inextricably with the film’s central theme of water. In doing so, it investigates the human costs of climate change and sheds light on intersectional links across social dimensions such as gender, socio-economic status, and access to education.

“We wanted to focus on the human side of climate change,” says co-director Deej Phillips, who also doubled as the DOP for the film. “The news already covers the latest scientific reports and statistics. We wanted to bring out the stories of the humans at the center of the crisis.”

The film began production on the backs of a Kickstarter campaign over two years ago. The campaign was primarily supported by the filmmakers’ family and friends at the beginning, says Philips.

“We were grateful to be able to start working independently,” says co-director Neelima Vallangi. “We also got a lot of support from social media. I often shared my worries about climate change on social platforms and thus had built a supportive community over time that we were grateful for showing up and helping when the project was announced.”

A year into filming, the project received support from UNDP Nepal.

The first of the three stories spotlights 42-year-old Kamala Devi Pathak, a mother of three and resident of Salyantar in Dhading district. Pathak juggles several household chores, including a three-hour trek fetching fresh water from a spring up to six times a week, with no help from the men in her household. Her story is not at all uncommon. A 2017 report from the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST) found that a large majority of women across the country balance paid work while exclusively fulfilling all unpaid care work both in and out of the home.

In recent years, studies conducted across the Himalayan range have found increasing evidence of freshwater springs either facing sharp seasonal reductions in discharge or drying up completely. A NITI Aayog report found that nearly 50 percent of springs across the Hindu Kush had dried up in the last three decades.

“Entire villages have been abandoned in the hills because of dried out springs,” shares former Minister of Water Resources Dipak Gyawali.

As nearby springs stopped providing water, Pathak’s treks became longer and more rigorous over the years. This consistent pressure on her body led her to suffer a uterine prolapse. While the exact size of the causal effect of physical exertion by fetching water on the issue is unknown, UNFPA estimates that 60,000 Nepali women suffer from uterine prolapse, suggesting that Pathak’s story is a lot more common than one may think.

The second story focuses on the climate crisis’ indirect community-level effects through the curious case of Hetauda’s Piple Youth Club. It recounts founder and head coach Sushil Ghimire’s journey as a successful boxer – having represented Nepal in several victorious international meets – to establishing the youth club in an effort to attract young people towards sports and away from the prevalent negative influence of substance abuse. Over the last three decades, Ghimire has led the club’s growth as it has expanded to include training for football, volleyball, and boxing.

In the last two years, the Piple Youth Club’s beloved outdoor football field – once an abandoned cattle grazing ground transformed by the club’s members themselves – was destroyed by a torrent of flash floods. It has long been scientifically established that climate change directly affects precipitation levels and humidity measures, causing rainfall to become less frequent and more intense, triggering floods. With the destruction of the Piple football ground, Ghimire is concerned if his community-building and youth-support efforts have been in vain. While he remains optimistic about the future of the club throughout the film’s runtime, the crisis’ effects on Hetauda youth may yet be worse as erratic rainfall and flash floods are projected to become more frequent in the near future.

“We stayed with Sushil while filming the Hetauda portion, which helped us appreciate the club’s value among the local youth,” Philips says about his filming experience. “We similarly stayed with a community member while filming in Salyantar, which again allowed us to gain a deeper perspective on the day-to-day challenges introduced by climate change. It also strengthened our belief in the importance of getting these stories out there.”

The third and most gut-wrenching of the stories chronicles the death of 13-year-old Sanchana Balami in a flash flood in the tiny, high-altitude town of Ghartikhola. After attending a ‘boarding school’ for a few years, Balami moved to a nearby government school due to financial pressures at home after the birth of her younger siblings. A shallow, bridge-less river flowing through town makes it impossible for the school to arrange transportation. Balami’s death occurred when she and her uncle were caught in a flood while crossing the swollen river during heavy rainfall.

“Sanchana’s story was challenging for us to film and produce,” says Philips. “We wanted to be as sensitive as possible. Telling the story visually was also a challenge.”

Ultimately, the team decided to rely on interviews with Balami’s family to share their side of the incident and its effects on each member. Not only is this segment handled with sensitivity and care, but it also manages to effectively communicate the shared trauma and helplessness among the larger community. Two years since Balami’s passing, there is still no bridge.

The Weight of Water is as engaging as it is educational. Although it is not an easy watch, the documentary manages to capture what so many scientific journal articles, news pieces, documentaries, and on-the-ground reports have failed to highlight: the human cost of climate change. The crisis is a superphenomenon that directly and/or indirectly touches all aspects of life. Through the stories at Salyantar, Hetauda, and Ghartikhola, The Weight of Water is successful in showing the complexity of the climate emergency, and how viewing its effects through an intersectional lens can further highlight its footprint in exacerbating socio-economic inequities.

“If there is a single call to action that comes out of this film, I hope it is that people are inspired to learn about climate change and spread awareness in any way they can,” says Philips. “One doesn’t have to be a scientist or journalist to talk about it. Anyone can help using their respective skills and positions.”

In a country as understudied and underrepresented in the global climate discourse as Nepal, my hope is that The Weight of Water’s success serves as inspiration for filmmakers, writers, and artists of all kinds to further explore the human side of the climate crisis. As activist Shreya KC puts it in the film, “The few countries that are mainly responsible for creating this mess deny its existential threat. …[the saddest part] is that most victims don’t know why all this is happening and what is causing their suffering.”

***

The Weight of Water

dirs. Neelima Vallangi & Deej Philips, 2021

68 mins.

For the updates on screenings and more, visit www.humancostofclimatecrisis.com

A short version of The Weight of Water is now streaming on the DW Documentary YouTube Channel:

Shuvam Rizal Shuvam Rizal is a Kathmandu-based researcher. He is the founder of Rizolve Sustainable Solutions, Research Lead at Governance Monitoring Centre Nepal, and climate change columnist for The Record.

COVID19

News

5 min read

The Valley’s CDOs got the government’s green light to clamp strict measures on account of rising case numbers

Perspectives

8 min read

Connecting and improving green open spaces can provide exponential benefits for the people and the environment, and allow a suffocating Kathmandu to breathe freely.

Photo Essays

1 min read

For the people living besides the Bagmati in Teku, every year the monsoon brings much devastation. And as local authorities do little to help, residents have no one to turn to but themselves.

Features

11 min read

A disproportionate number of local representatives who own construction companies are facilitating the haphazard carving of roads across the fragile hills.

Features

Longreads

32 min read

Is maintaining the Kodari crossing between Nepal and China as an international highway a lost cause?

Features

4 min read

By helping them understand the importance of balanced feed, a Nawalpur-based grass resource center is providing farmers with the means to grow and balance their own livestock feed.

COVID19

News

4 min read

A daily summary of Covid19-related developments that matter

Perspectives

Film

8 min read

This feature documentary highlights the direct and indirect costs of climate change through three unique stories across Nepal, linked by its central theme: water.