Writing journeys

9 MIN READ

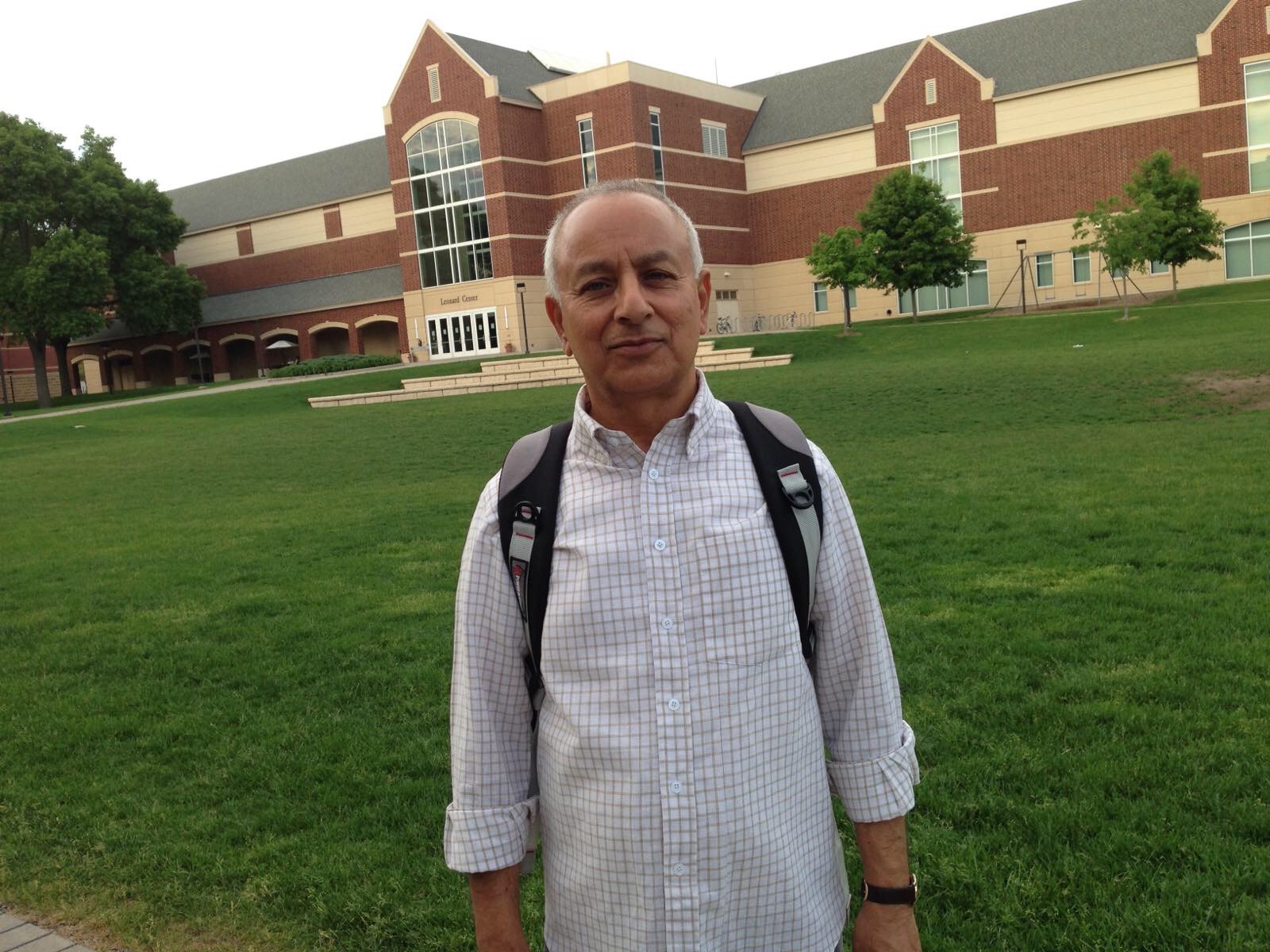

Nepal’s preeminent sociologist, on this week’s Writing Journeys, offers insight into his academic journey, and asks students to read actively and question the text.

For many years, the sociologist Chaitanya Mishra has been one of the leading lights of Nepal’s academic world, always bringing fresh insights to the understanding of Nepal’s changing socio-economic landscape.

In this engaging interview, Chaitanya sir offers observations about his own academic journey: the changes he has witnessed growing up near Kathmandu, how maps and fiction stoked his curiosity when young, how he learned English, why he chose research and teaching as a profession, and his goals for a new ‘University of Nepal’.

What I find particularly interesting are Chaitanya sir’s ideas about what he calls “active reading”. Too many students, he says, have too much reverence for what they are reading, as if each book is a sacred text “beyond questioning.” Instead, students “should agree, disagree, ask questions, question assumptions” about what they read. He wants students much more personally engaged in their reading; they should be weighing each sentence against their own experience to assess whether it adds up or not. He has a memorable way to express this: He wants students to write in and on their books — “not out of anger but with curiosity and love, as if … chatting with the author who is seated across your table.”

Chaitanya Mishra teaches Sociology to MPhil and PhD students at Tribhuvan University. He has authored and edited 10 books and published numerous articles. He writes mainly on social change and the nature of polity and economy from a world-systemic perspective. He is now working on frameworks for teaching as well as researching Dalit and non-Dalit social relations. He also works with a team that aims to form the University of Nepal in Gaindakot, Nawalpur.

Find all of the previous Writing Journeys here.

Next Week: Dev Datta Joshi

***

Where did you grow up? Was it a good place to grow up? As a sociologist looking back, how would you describe it?

I grew up during the 1950s in the immediate outskirts of what was then the town of Kathmandu. The place had a distinctly rural feel. There was no road; cows and goats and chicken roamed free; you could watch, during the summers, rice plants swaying in the winds; and I had been inside all homes in the neighborhood by my late childhood. I knew just about everybody.

But the place was also shedding ‘tradition’ and changing. Children’s names had begun to change, for example, from Ram to Kamal and Sita to Geeta. Clothing was changing and younger men had begun to strut in pants. Schools had just begun to crop up and most young children attended. Separation and inequality based on caste and gender were pronounced. Bahun-Chhetri parents would ask their children to not make friends with “lower caste and riffraff” children. But even here, change was in the air.

How did you get excited about reading and writing?

I was excited to read maps early on. Land and water, sun and moon, this country and that country, this capital and that capital, temperature and rainfall, and so on. That was hot stuff.

However, during my school years, that was about it. I started enjoying reading Hindi and English novels – and gradually, textbooks – only later during my college years. And I cannot say I really enjoyed writing till maybe during my early thirties, when my job as a researcher could otherwise have come into peril.

Did you have favorite teachers, especially for reading and writing?

I had an English teacher during Grades 4 and 5. His name, I think, was Krishna Lal Tandukar. He genuinely liked children. And he knew what children liked: love, motivation, and something sweet. He always came to the class with tiny, round, colored candies. That was, of course, out of his own pocket. And he found ways to give at least one to each child. Those who had the homework ready perhaps managed to get 2-3 of the round stuff. But no student left empty-handed.

Of course, I had some good teachers during my college years: Mohan Himanshu Thapa and Kedar Mathema, for example, who taught me Nepali literature and English literature, respectively. But my favorite college teachers were nothing like my school teacher who had curly hair and always entered the class with a twinkle in his eyes.

Who are your favorite Nepali writers or books/articles and why? What about them do you like? Favorite non-Nepali authors?

I am not much into literature. I did read some during my early years but it is almost a rarity these days. I list the names with much trepidation. I like BP Koirala, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, Bala Krishna Sama, Bhimnidhi Tiwari, Dhanush Chandra Gotame, Bhupi Serchan, Jagadish Ghimire, Indra Bahadur Rai, Lil Bahadur Chhetri, Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha, Ahuti, Narayan Dhakal, Abhaya Shrestha, Sarita Tiwari, Sarala Gautam, and a few others.

The answer will be much too long if I were to tell you why I like them. Let me just note that I like them for various, often disparate, and sometimes contradictory reasons.

In the line of my work, I like Father Ludwig Stiller, Mahesh Chandra Regmi, Kamal Prakash Malla, Prayag Raj Sharma, brothers Kunda and Kanak and Dixit, and some others.

What made you decide to become a researcher? Why a sociologist?

I continue to wonder about that myself. I do not believe things occur accidentally, but my entry into Sociology comes close to it. I came across the word ‘Sociology’ for the first time when I was 18. I found it in a call for application for funded graduate study in Sociology in India in Gorkhapatra Daily. I applied for it and, lo and behold, I was selected. In due course, I became a sociologist.

Beginning my early years, I did wish to teach at a university someday. Maybe because of my school teacher with the twinkle as well as candies, or that one of my maternal uncles provided tuition to school kids, or maybe because I came from a Bahun family? Or maybe that it was a valued profession with a steady income? I shall never know, really. But that came true as well.

I have enjoyed my work through the years. I have been lucky all along. And as far as the sequence of my ‘accidents’ goes, I have tended to believe that you will get your chance if you stand in line and, when necessary, bide your time.

How did you learn English?

I am still learning the language. I continue to frequently make mistakes. What English I have learned, however, has mostly been due to the fact that I love languages. I used to be intrigued by how different languages use different words for the same item, a dog or water for example. A dog was kukkur, khicha, kukkuta, and so on, for example.

With respect to English, I did my homework as well. A few teachers have been helpful along the way. I also enjoy languages because they are windows into specific cultures and histories. I knew, of course, that without English much of the world and history would pass me by.

What part of writing do you find hard?

I find it difficult to describe things, i.e., answer the question ‘what?’. I somehow feel as though that were a superfluous task, inasmuch as people around me see and feel the same things and processes and their apprehension will be similar to mine. I know that is not really the case. Careful observation and description are necessary for adequate communication. But I wish I did not have to take on that task.

On the other hand, I enjoy explaining, i.e., seeking to answer the question ‘why?’. One of the questions that intrigued me during my childhood was, Why didn’t it rain in all places at the same time? Another one, for example, was why do we have the caste system?

What mistakes do students and young academic writers make?

Most students are not trained to intrude into the text they are reading. They feel as if reading can be accomplished without self-engagement, investment of one’s self, and questioning and commenting upon the text.

Part of the reason for this is that most students think that they are reading ‘big men’ from powerful countries and universities who are beyond questioning. In addition, in Nepal, we have long had a culture that discouraged the act of ‘questioning your superior’.

Are there certain tips or tricks or things you do that you would like to share?

I recommend active reading. Each student should delve into a text with the belief that the text being read is not about some abstract and faceless author and reader(s) but about himself or herself and real-life issues. They should feel free to react to the text based on their own knowledge and experience. They should agree, disagree, ask questions, question assumptions, and so forth. My tip is to render the face of the text dirty by scribbling all you want across its face. Not out of anger but with curiosity and love, as if you were chatting with the author who is seated across your table.

When you do that, you have suddenly upped the ante on the investment of your own self about the pages you are reading. That’s what I mean by active reading.

Which sociologists or other scholars do you think write particularly clearly and engagingly? Any favorites? What about writings about Nepal?

Oh, there are so many. So, I will limit myself to a few ‘non-Nepali’ writers who write about Nepal. Jim Fisher writes very well. Among others, Richard Burghart, John Gray, Andras Hofer, and David Gellner write well. If I may, Tom, you are no slouch on this front either!

Do you think Nepali students in high school write enough? Can they be doing more writing in social studies?

To the first question, no, not at all. As to the second, definitely.

Teachers, students, and administrators all have to contribute to developing a classroom culture that relies on expanding the horizon of curiosity, intensifying the investment of self, and promotion of communication, both spoken and written. Regular classes, similar to those on other subjects, have to be organized to promote good reasoning and writing. Promotion of independent thinking must become a key goal at all levels of schooling.

Will writing be a part of the new university you and Dr Arjun Karki have been working on? How does it fit in?

Yes. The projected University of Nepal will place a heavy emphasis on independent thinking and communicating, including writing.

Where do you like to write and at what time of day?

Almost all of my work takes place during the day. When required, I can start my morning quite early. Except for times when I exceed a deadline, I close my shop by late afternoon.

Anything else you’d like to add?

I read Kunda Dixit’s ‘writing journey’ in this series. I have disrespected his admonition to write clearly and concisely by quite a stretch. I must stop here.

***

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Perspectives

18 min read

For Nepalis living abroad, family is always a scattered reality, and every goodbye can feel like the last

Writing journeys

30 min read

Or, why I love vigorous verbs and why you should too

Writing journeys

12 min read

Ujjwal Prasai recounts his time growing up in Kakarbhitta and struggling with writing before coming to Kathmandu and establishing himself as a columnist and writer.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week, for Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson asked contributors what they enjoy most about writing. Here are their answers.

Writing journeys

6 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson takes apart an older article of his, line-by-line, providing critical insight into what makes a good essay.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, Kunsaang narrates growing up in the mountains of Humla, studying from books that did not represent her, and writing to remember.

Writing journeys

11 min read

Writer and reviewer Richa Bhattarai fondly reflects on the reading and writing habits instilled by her father in this week's Writing Journeys.

Writing journeys

8 min read

Kathmandu University professor Laxman Gnawali relates a particular instance from his own writing journey that taught him how to better teach writing to young students.